Kate Middleton and Samuel Ray Gates as Lily and Joshua in the world premiere premiere of “Alabama Story” at Pioneer Theatre Company in Utah.

Photo by Alex Weisman

“Alabama Story”—Recent play tells the story of librarian Emily Wheelock Reed, her strength, fortitude in the face of misunderstanding, intolerance

Rev. Jerrod H. Hugenot

March 20, 2020

Women’s History Month is observed throughout March, encouraging more exploration, recognition, and reclaiming of the powerful yet often obscured words and actions of women from times past and current when the dominant narratives have tended to exclude outright or conveniently “forget.” By seeking the fuller narrative of women in history and today, we have to ask hard questions of why our histories are handed down often with omission and occlusion, and what that enlarged story changes about how we understand that past and course corrects our present as we move toward a more inclusive future.

The recent play “Alabama Story” by Kenneth Jones would serve well as part of this effort to remember the past and live for a different future. Jones sets his two-act play in 1959 Montgomery, Alabama. Jim Crow laws and attitudes are well entrenched, yet a children’s book starts an uproar when it is recommended by the Alabama Public Library Service. At the epicenter is a very determined librarian who takes on many systems (seen and unseen) in making sure children have access to enlightening literature.

Kenneth Jones’ recent play “Alabama Story,” set in Montgomery in 1959, reminds us to remember the past and live for a different future.

At the epicenter of the conflict over a children’s book opposed by segregationists is a very determined librarian who takes on many systems (seen and unseen) in making sure children have access to enlightening literature.

Kenneth Jones first learned of Emily Wheelock Reed, one-time State Librarian and director of the Alabama Public Library Service, upon reading her obituary in The New York Times. The obituary recounts her steadfast courage with these opening lines:

Emily W. Reed, who in 1959 enraged Alabama segregationists by allowing a book about a fuzzy white rabbit marrying a fuzzy black rabbit onto the shelves of the state’s central library, died on May 19 at a retirement community in Cockeysville, Md. She was 89.

Jeanne Paulsen as Emily Wheelock Reed in “Alabama Story” at Repertory Theatre of St. Louis in 2019.

Photo by Jon Gitchoff for The Rep

Entitled “The Rabbits’ Wedding,” suitable for readers 3 to 7 years of age, the story of a white bunny marrying a black bunny enraged Southern critics who were certain the book was encoded with support for interracial marriage and integrationist ideals. Ms. Emily Wheelock Reed, State Librarian and director of the Alabama Public Library Service, supported the book’s promotion and resisted citizen groups and politicians actively trying to have the book removed, censored, banned or, if need be, terminating Reed herself as well.

Jones constructs his play around these events, highlighting the high stakes felt by white citizens of Southern states as times changed and their ability to maintain a self-serving status quo started to erode with bus boycotts, non-violent protests and yes, even a children’s book about bunnies, suitable for ages 3 to 7 years.

My librarian wife and I enjoyed an afternoon performance of “Alabama Story” at the Albany (NY) Civic Theatre as part of their Fall 2019 season offerings. A small venue theatre, the Albany Civic Theatre provided an intimate space to enjoy the action unfolding and the quiet moments as characters reflected on the chaos being stirred up by the questions of censorship and long entrenched social order being questioned.

In the play, Emily Wheelock Reed is warned of the impending furor by her assistant Thomas, who brings her a local segregationist newspaper The Montgomery Home News, which lambasts the propriety of their state-funded library recommending such a book. Shortly thereafter, an Alabama state senator, E.W. Higgins, arrives at her office door. (Jones opted to create a fictive character, based on the real-life politician turned censor E.O. Eddins). Higgins is hopeful for a quick withdrawal of the book’s recommendation. After Reed’s firm refusal, he escalates his threats by summoning her to a budget hearing where Higgins grills her about the book:

SENATOR HIGGINS: The part that interests me is in the very first sentence of the story.

EMILY: Do you know it by heart?

SENATOR HIGGINS: No, I do not. But I have a copy here. (He opens the book. Clears his throat.) “Two little rabbits, a white rabbit and a black rabbit, lived in a large forest…” What does that say to you?

EMILY: I think we ought to ask children aged three-to-seven-years-old. They are the intended audience.

SENATOR HIGGINS: Miss Reed, my bad ear isn’t so bad that I don’t hear the vox populi. It says that this book is a vehicle to promote integration. To our youth. To our impressionable youth. Our “three-to-seven-year-olds”! The state House has heard about this book, the state Senate has heard about this book. The people do not like this book.

EMILY: The Montgomery Home News does not like this book.

SENATOR HIGGINS: And the Montgomery Home News represents many people.

EMILY: The paper represents members of the White Citizens Council.

SENATOR HIGGINS: And members of the White Citizens Council are residents of the state of Alabama, Miss Reed. Bawn [born] ‘n’ bred. And although things may be different in Indiana, we have our ways — people stay with their own kind.

EMILY: What would you like me to do, Senator?

SENATOR HIGGINS: I think it would be prudent for The State Librarian of Alabama to pull this book from the shelves of the Alabama Public Library Service. And she should recommend that her librarians around the state do the same.

EMILY: I will not do that.

(Dialogue from the script provided for review, p. 43-44)

The play also features periodic scenes between Joshua Moore and Lily Whitfield, two young adults who grew up in Montgomery. Joshua left the South a decade prior, finding more opportunity for African Americans in the North, and Lily became the quintessential mannered Southern belle. The two reconnect during brief encounters in the town green spaces, where Lily reads a book and Joshua is cutting across town on foot as he has few choices for transportation when back home. The two catch up about their past. They knew each other as children, when Joshua’s mother worked for Lily’s father. Yet as their storyline plays out, they realize that their past (and their present) is burdened by pain not seen or understood by Lily and endured by Joshua at the expense of Jim Crow privilege.

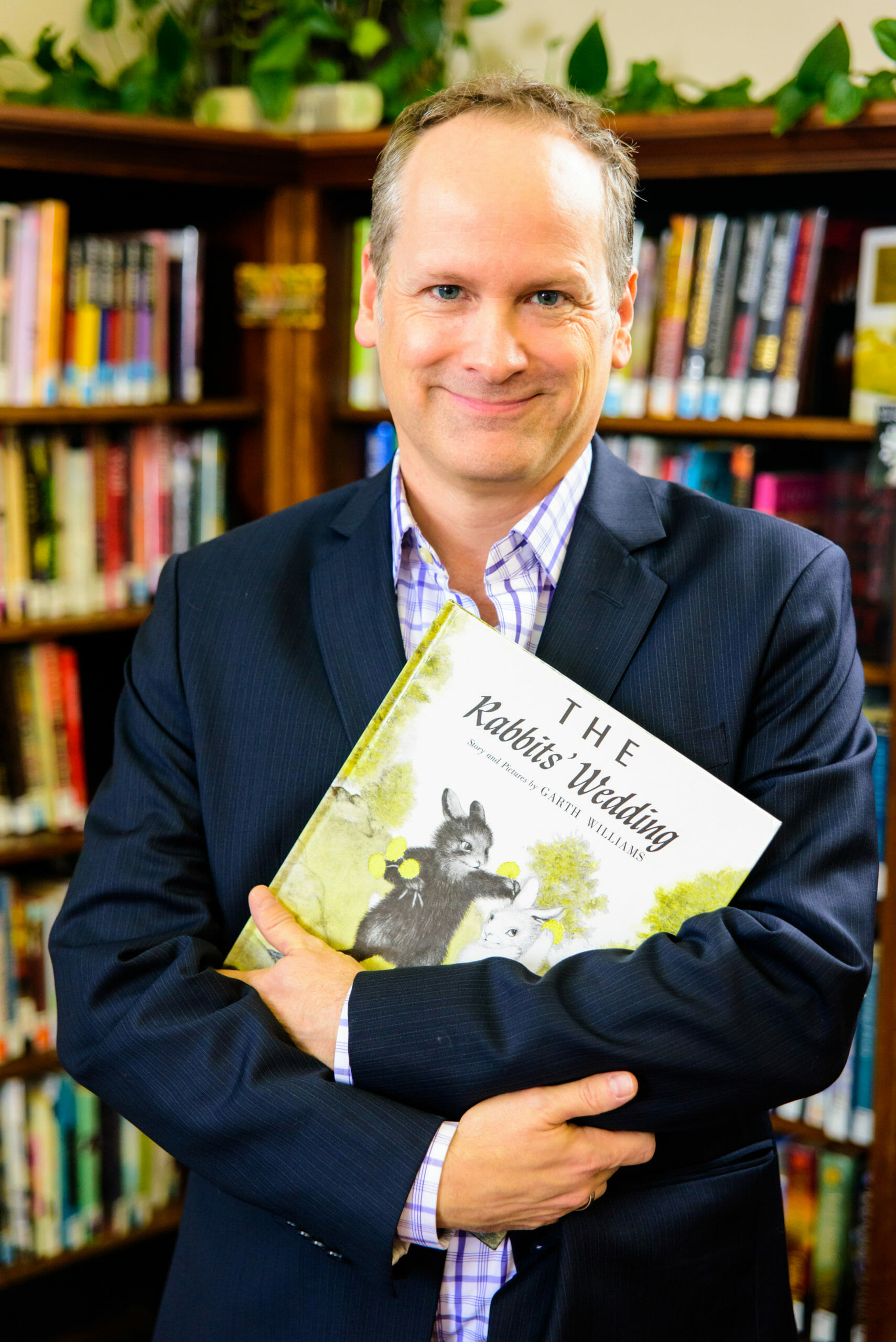

Playwright Kenneth Jones, holding a copy of “The Rabbits Wedding,” the controversy over which prompted international headlines and inspired Jones’ play “Alabama Story.”

Photo by Alex Weisman

The controversy over “The Rabbits’ Wedding” makes headlines across the nation. Reed is hailed as a supporter of libraries, except back in Montgomery. Senator Higgins works feverishly to call Reed to account, yet as time passes, some politicians begin advising Higgins to forget the “bunny book” due to all the attention. Reed’s determination to weather the political furor may waver at times in the play, yet she sees the Library through the storm of controversy, never rescinding her recommendation lists or more importantly, never removing any contested book from the shelf.

While “Alabama Story” is set in late 1950s Montgomery, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s presence is off-stage, yet powerfully felt as Montgomery’s black churches grow in their organizing and activism. In the Joshua and Lily scenes, Joshua notes he is going to help out at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church where King served as pastor. Lily politely expresses no familiarity with there even being an African American Baptist church on Dexter Avenue. King’s book “Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story” appears on a later American Library Association’s recommended reading list distributed by Reed’s office, again with no qualms given to the immediate backlash from her growing cadre of critics.

Senator E.O. Eddins (Left) and Emily Wheelock Reed (Right)

Garth Williams, the author and illustrator of “The Rabbits’ Wedding” and even better known for his illustrations of the works of Laura Ingalls Wilder and E.B. White’s “Charlotte’s Web,” appears occasionally in the play, serving as a narrator, and with no end of wry commentary. The character observes at the opening of Act Two:

It’s my parents’ fault: My father was a cartoonist, my mother a landscape artist. Everybody in my home was always either painting or drawing. They exposed me to books filled with art from all over the world; the most outrageous and arousing images! And so my goal, like their goal, is to drown children in a watercolor world of the most unspeakable aspects of the human experience. Namely: kindness, tolerance, amity, tenderness, humor, joy, respect for others, interest in the natural world and…hope for the future.

For the record? Pencils ready? I was completely unaware that animals with white fur were considered blood relations of white human beings. The book was written for children, who will understand it perfectly, as it is only about fuzzy love. It was not written for adults; they are not smart enough to understand its simplicity. It has no hidden political message. It was never intended to wake the sleeping giants of hate.

Anyone with a rudimentary knowledge of art will know that the rabbits are a different color for visual contrast. My book was published in black and white! My inspiration was 11th-century Chinese art: visual balance; yin and yang; dark and light. As in Chinese scroll art, I just think a black horse next to a white horse looks more picturesque. But that sounds a bit grand, or worse — like an explanation. And art owes no explanation.

A bit later in his monologue, Williams notes,

My publisher, Harper Brothers, has informed me that my romance about two herbivorous creatures is shaping up to be one of my best-selling titles ever. I couldn’t have done it alone. I’d like to thank Senator E.W. Higgins, the great champion of children’s literature! We never even knew that we needed him! (Dialogue from the script, p. 50-51)

A note for persons interested in staging the play: The play’s ensemble cast list of six actors lends itself to small-scale production companies, hopefully a boost to similar groups taking on the staging of the play when opportunities arise. In 2020, the play is slated for performances in Abilene, Kansas; Crossville, Tennessee; Arkadelphia, Arkansas; Springfield, Illinois; and for the first time, its setting of Montgomery, Alabama. Playwright Kenneth Jones’ website has further details about the production and performance rights, etc.

This play reminds us of the strength and fortitude of a remarkable woman, the librarian Emily Wheelock Reed, against the pressures of misunderstanding and intolerance.

Rev. Jerrod H. Hugenot is the Associate Executive Minister of the American Baptist Churches of New York State.

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.