Mandate from heaven? A brief primer in political theology

Claire Hein Blanton

February 17, 2020

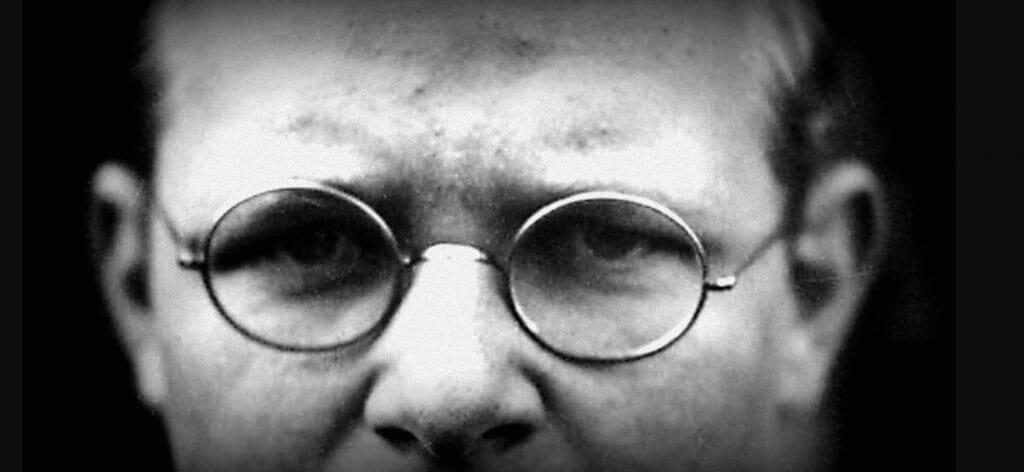

Every so often, my research in political theology becomes interesting to those outside of the theological academy. This is particularly true during the long election seasons in the United States. That my research focuses on the political theology of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, prolific writer, theologian and martyr during the reign of the Third Reich, added significance to the conversation toward the end of the 2016 presidential election. Radio show host Eric Metaxas wrote an opinion piece for the Wall Street Journal in which he suggested that Bonhoeffer would have voted for Donald Trump, and as Christians, we should have clear consciences in choosing to vote for then candidate Trump.[i] The response from Bonhoeffer scholars around the country decried this opinion, noting that Trump was antithetical to Bonhoeffer’s political leanings, among many other reasons.[ii]

While the debate over Bonhoeffer’s political allegiances is fodder for good reflection and debate, it sidesteps a more fundamental question – does God care about who Christians vote for and does God endorse certain candidates? Is there a “mandate from heaven” directing certain individuals into certain offices? The courting of the evangelical vote in the United States suggests that politicians, at least, believe that a large swath of Christians believe that God is actively engaged in the politics of the United States. The rise of the Moral Majority in the 1980s likewise evidences that politicians are not wrong in this summation. Evangelicals, in particular, have a recent history of directly engaging with the political process to get “God’s” candidates elected.[iii] Political theology, however, does not unanimously support these claims.

Does God care about who Christians vote for and does God endorse certain candidates? Is there a “mandate from heaven” directing certain individuals into certain offices?

Thus, to offer a brief picture of how we got to this point, theologically speaking, I will provide a primer in the development of political theology. From the very beginning of theological discourse, two streams of thoughts on the role of government have taken hold. The first, rooted largely in the works of Augustine (although he was not the first to espouse such a viewpoint) is that government/the state was created by God after the Fall to keep humans in check from our worst behaviors. This is the “City of Man,” where the lawlessness of sin rules. In contrast is the “City of God,” which has a reflected presence in the world in the form of the church.[iv] The other major stream of thought stems from the works of Thomas Aquinas, leaning on Aristotle’s understanding of politics, that government/the state was part of God’s plan from the beginning. Aquinas argued that God foreknew that humans needed some sort of organizational body to guide them into being more virtuous.[v] The government, then, aids in that endeavor by keeping vices in check through rule of law.

These views underscore almost all of modern political theology. Luther took the Augustinian track and argued that temporal authority exists to keep humans from our worse behaviors.[vi] Calvin went the Thomistic route and believed that government could assist in the development of better behaviors.[vii] Both, however, maintained that church and state remain separate. While Romans 13 instructs the church to obey and pray for those governing them, it never directly states that the church should be overly involved in the state. Early writings support this. Only after the conversion of Constantine and the promotion of Christianity as a state religion do we historically see the messaging of the church shift.

While historical arguments are interesting, I suspect that these arguments do little in the way of “winning” political arguments about God’s endorsement, or non-endorsement, of a particular candidate, or to answer the lingering question of whether the church should be actively engaged in the election of individuals that claim to support and empower the church. Rather than provide a longer list of theological claims, the answer lies more fully in the overarching narrative of the Bible. God commands first Israel and later the church to care for the least of these (Exodus 22:21-24, Deuteronomy 27:19). Throughout the major prophets, Israel is lambasted for its failure to do so, and even worse that it has allowed the least of these to be exploited instead of what God desires (Isaiah 1:17). Perhaps the earliest manifestations of the church knew this better, when it was comprised of those largely on the outskirts of society.

The church should care about the election and being engaged with the political process, but not in the way that it currently is. God seems to care less about the words spoken by candidates to curry favor and votes and more about whether that individual will do the work of caring for those on the outskirts of society. Those outside of Israel were routinely used in God’s good work for both creation and specifically Israel. The person sitting in the seat of power does not need to be the obvious “Christian” candidate for God to work good through him or her.

The church should care about the election and being engaged with the political process, but not in the way that it currently is. God seems to care less about the words spoken by candidates to curry favor and votes and more about whether that individual will do the work of caring for those on the outskirts of society.

Instead of throwing our support behind candidates that promise power and glory to the church, let us throw our support behind policies and organizations that offer support to those around us that most desperately need it. Perhaps a candidate for an elected position will champion those causes, perhaps not. The state is not the church. We should not expect it to be, nor should we try to make it into the church. We are called to so much more than our political leanings, and in this election season I pray that we would remember that amidst the pundits and the candidates trying to tell us otherwise.

Claire Hein Blanton is an ordained Baptist minister in Houston, Texas. She is currently studying for her PhD in systematic theology and ethics from the University of Aberdeen.

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.

[i]Eric Metaxas, “Should Christians Vote for Trump?” Wall Street Journal, October 12, 2016. https://www.wsj.com/articles/should-christians-vote-for-trump-1476294992

[ii] Stephen R. Haynes, “Has the Bonhoeffer Moment Finally Arrived?” Huffington Post, November 28, 2016. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/has-the-bonhoeffer-moment_b_13275278

[iii] John Fea, Laura Jane Gifford, R. Marie Griffith, and Lerone A. Martin. “Evangelicalism and Politics.” Organization of American Historians, The American Historian, November 2018. https://www.oah.org/tah/issues/2018/november/evangelicalism-and-politics/

[iv] Augustine, The City of God.

[v] Thomas Aquinas, Political Writings. R. W. Dyson (ed.) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002, p. 4.

[vi] Martin Luther, On Temporal Authority.

[vii] Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, Book Four, Chapter 20.