The letter that liberates

Rev. Jerrod H. Hugenot

January 18, 2021

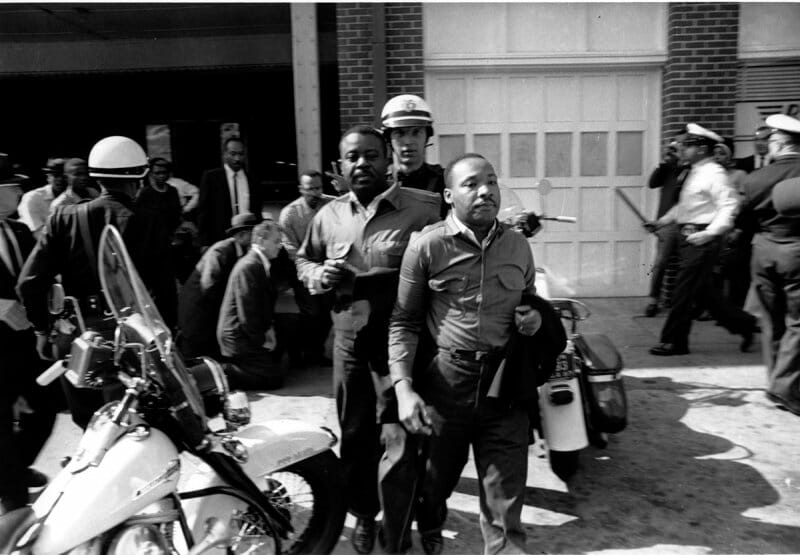

On this MLK Day 2021, I revisit Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail, written in April 1963 during segregation protests in Birmingham, Alabama. King and other leaders protested, knowing that a Circuit Court judge placed them under an injunction banning “every imaginable form of demonstrations including boycotting, trespassing, parading, picketing, sit-ins, kneel-ins, wade-ins and the inciting or encouraging of such acts.”

Undeterred, the protesters conducted pickets, occupying segregated public spaces, and sitting down at lunch counters to challenge local Jim Crow laws. King welcomed the injunction threat, announcing his intention to be arrested on Good Friday, so that the protestors could “march for freedom on the day Jesus hung on the Cross for freedom.”

King’s aligning of the Birmingham protests with Christ crucified did not resonate with some area white clergy. On April 13, 1963, the Birmingham News carried the remarks of eight moderate ministers who decried the protest and civil disobedience. The local clergy group said, “Just as we formerly pointed out that ‘hatred and violence have no sanction in our religious and political traditions,’ we also point out that such actions as incite hatred and violence, however technically peaceful these actions may be, have not contributed to the resolution of our local problems. We do not believe that these days of new hope are days when extreme measures are justified in Birmingham.” [1]

King read their remarks while in a barely furnished prison cell. He began to write on scraps of paper with his response. Biographer Taylor Branch notes when NAACP’s Clarence Jones visited the jail, King “had pushed a wandering skein of ink into every vacant corner” of his jail cell.[2] Once typeset after being smuggled out of jail by supporters, the document weighed in at twenty-one pages long, single spaced.[3] The Letter from a Birmingham Jail would see its first major media publication in brief excerpts and by that summer in full-length features of The Christian Century and The Atlantic.

Beginning with a cordial salutation (“My dear fellow clergymen”), King responds at length to the clergymen’s criticism that the protests will not lead to solutions. King was not ready to equate his time in a barely furnished jail cell with a failure to address desegregation in Birmingham and the wider country. Indeed, he writes to these critics:

You deplore the demonstrations taking place in Birmingham. But your statement, I am sorry to say, fails to express a similar concern for the conditions that brought about the demonstrations. I am sure that none of you would want to rest content with the superficial kind of social analysis that deals merely with effects and does not grapple with underlying causes. It is unfortunate that demonstrations are taking place in Birmingham, but it is even more unfortunate that the city’s white power structure left the Negro community with no alternative. [4]

King laments the white moderate’s failure to embrace the urgency driving these non-violent protests. Secular readers certainly find much wisdom about the nature of protests of social and governmental ills, yet the Letter brings to bear King’s greatest critique on churches and Christians, particularly those who seek moderate change, yet then give little heed to the times at hand and distance themselves from the injustices entrenched all around them.

King observes,

Things are different now. So often the contemporary church is a weak, ineffectual voice with an uncertain sound. So often it is an archdefender of the status quo. Far from being disturbed by the presence of the church, the power structure of the average community is consoled by the church’s silent—and often even vocal—sanction of things as they are. But the judgement of God is upon the church as never before. If today’s church does not recapture the sacrificial spirit of the early church, it will lose its authenticity, forfeit the loyalty of millions, and be dismissed as an irrelevant social club with no meaning for the twentieth century. Every day I meet young people whose disappointment with the church has turned into outright disgust.[5]

Reading the Letter myself, I linger over this section, feeling particularly the incisive power of King’s warning about Christians not being authentic to the Gospel. I have been that “young” person who has struggled with the church and its reticence to engage hard questions. And now as a clergy person, I do lose sleep pondering what I have done to perpetuate gradualism when it comes to matters of justice where disagreements and discord are heightened among the faithful.

A few months ago, an African American pastoral colleague asked when I connected with our congregations around upstate New York how other churches were addressing the challenges at hand. He asked if other churches and pastors were aware that the United States was amid two pandemics? By this, he referred to both the COVID-19 pandemic and the eruption of issues of race still unresolved in our history as a nation.

Certainly, I could identify some churches where this sense of a “double pandemic” was indeed being addressed in sermons and social media posts and as possible in COVID-19 times, to take up protest, advocacy, and action opportunities. Other churches focused more of 2020 on the multiple internal challenges and logistics presented by COVID-19 restrictions and the understandable conflict and grief that accompanied these obstacles. Yet, I sense that some churches were not talking much about the headlines this past year, whether it was the election season or the social unrest that rose up in urban and not so urban contexts.

In his Letter, King saw with clarity from a jail cell what many in Birmingham could not or would not perceive in the social order’s status quo predicated on segregation and inequality. I prayerfully hope that we will experience indictment anew from King’s Letter as a people gathering to celebrate King’s witness just weeks after early January’s national turmoil. The myopic habits to exclude and occlude others in society are still strong in the American psyche and certainly proved pernicious in the last few years—and devastatingly so in recent weeks.

I would beg a little grace that churches have struggled to get together for much of anything this year and have a lack of “bandwidth” to do much. Nonetheless, I know that some faith leaders will see some form of socio-political tumult and demurely (at best) suggest it is not yet “the time” to deal with complex and longstanding societal ills.

However, the events of January 6, 2021, warn that the gradualism King unveiled about Civil Rights and the white moderate Christians is with us today, and demonstrate how these lessons from history must be engaged. The day began with Dr. Raphael Warnock, King’s current successor at Ebenezer Baptist Church, elected to the U.S. Senate. By midafternoon, the U.S. Capitol Building was on lockdown, prompting an emergency evacuation of legislators, staff, and the Vice President. Meanwhile, persons toting Confederate flags and other disturbing symbols of their worldview[6] went about the looting of Congressional offices, attacking security officers, and then occupying the House floor and the Senate rostrum—all in the hope of disrupting our country’s peaceful transition of power as Congress met to certify the Electoral College ballots.

While we have been stressed greatly by a public health emergency, the consequences of America ignoring or denying other longstanding social ills and systemic racism have poisoned the nation. We must act decisively to root out ideological demagoguery guised as political speech, for in gaining power and the tools of government, we see how such a mindset can translate into the steady disenfranchisement of so many. Our better angels, as Lincoln once imagined, still await our embrace.

In his Letter, King saw with clarity from a jail cell what many in Birmingham could not or would not perceive in the social order’s status quo predicated on segregation and inequality. I prayerfully hope that we will experience indictment anew from King’s Letter as a people gathering to celebrate King’s witness just weeks after early January’s national turmoil. The myopic habits to exclude and occlude others in society are still strong in the American psyche and certainly proved pernicious in the last few years—and devastatingly so in recent weeks.

In 2020 and in the early days of 2021, we have learned that we are not far removed from the challenges presented by Birmingham in 1963. Whenever it is read, King’s Letter engages the here and now, not some long-gone past.

In 2021, will we dare to let this Letter liberate us once more?

The Rev. Jerrod H. Hugenot is associate executive minister, American Baptist Churches of New York State.

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.

[1] As quoted in Taylor Branch, Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954-63. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1988, p. 738.

[2] Ibid., 738.

[3] The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University provides access to a PDF file of the Letter’s typeset draft as well as an audio file of King reading the Letter. See this link: https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/king-papers/documents/letter-birmingham-jail.

[4] The Christian Century published King’s Letter in their June 12, 1963 print edition, and today, they provide the text for free via their website: https://www.christiancentury.org/article/first-person/letter-birmingham-jail.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Robert P. Jones provides a perceptive analysis of the “image” various rioters brought into the Capitol with them here: https://religionnews.com/2021/01/07/taking-the-white-christian-nationalist-symbols-at-the-capitol-riot-seriously/