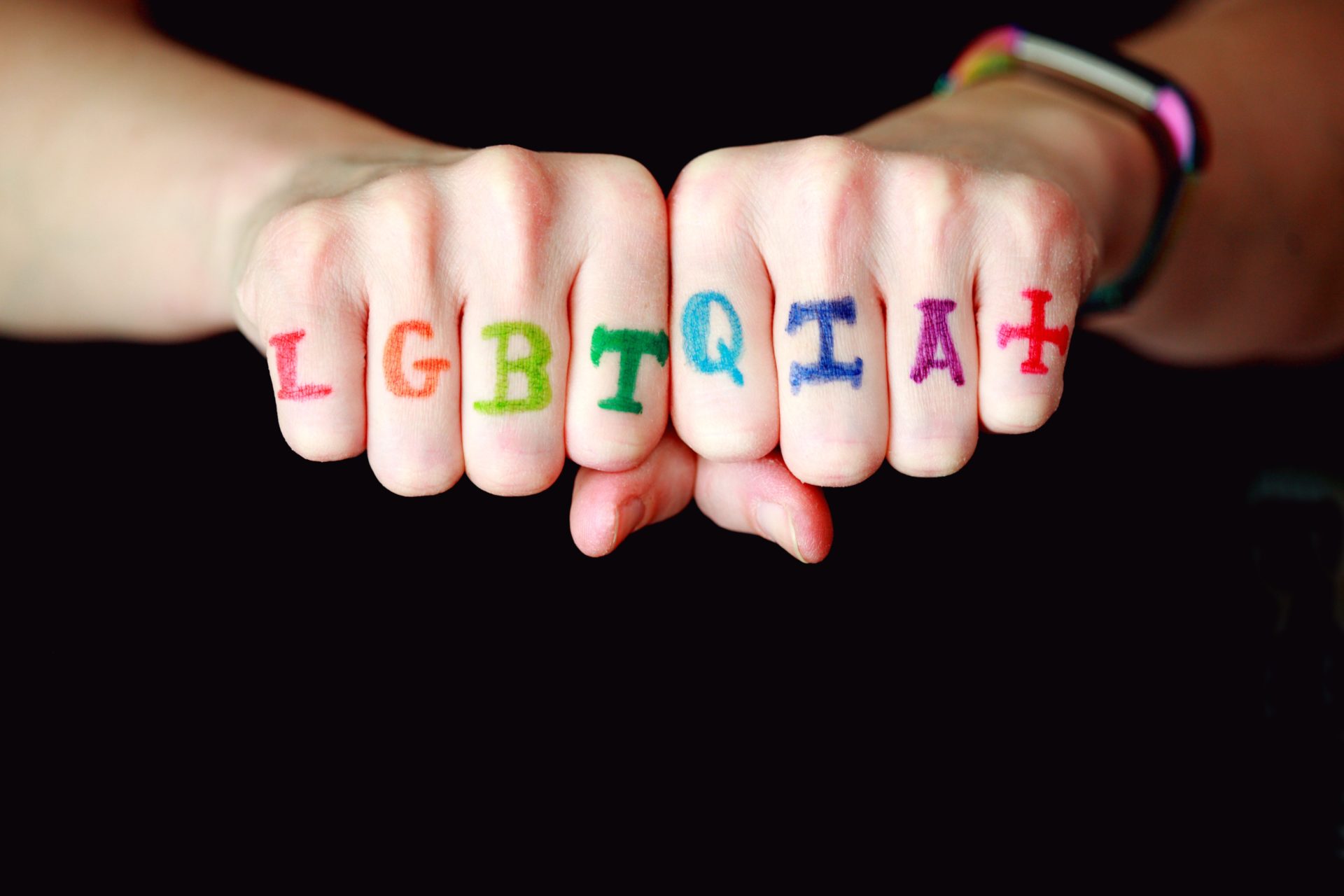

Photo by Alexander Grey on Unsplash

A guide to progressive church

February 1, 2023

Adjectives are problematic. Although they help us know something is one sort of thing rather than another sort of thing, they also then invite us to believe or trust the meaning of the way they modify by narrowing. For example, take the noun “church.” We all have a rough semantic sense of what a “church” is. It’s an assembly, a gathering of the faithful: in specifically Christian terms “the body of Christ.” It’s also the word used to describe the building in which these kinds of assemblies gather, and from which such assemblies stage their neighbor-love in the world and their love of God in worship.

But once we start adding adjectives in front of that word “church,” we begin to introduce complications. For example, if you say you belong to a “Lutheran” church, this invokes an entire history of certain churches who are separated from or unique in comparison to other churches. We might say Lutheran churches are Protestant, or they are heirs of the Reformation, or they are a denomination in which certain gifts or charisms of the more general “church” are present. But then we’d also have to start asking which kind of Lutheran. Do we mean the more conservative Lutherans like the Missouri Synod, or the more liberal Lutherans like the ELCA? What does “Lutheran” even mean?

This is how the adjective becomes problematic. It can only carry a certain amount of meaning and beyond that, each adjective can be broken. It can mean mutually contradictory things for which additional adjectives will be required.

Let’s take the word “progressive.” Increasingly, I’ve become attached to this adjective as the primary descriptor for the kind of church I pastor. This isn’t to say that the church I pastor isn’t also “Lutheran” or “Protestant” or “Christian.” It’s all of those things in various ways. But I would argue that the best one word to describe our church is “progressive,” even if that adjective is problematic.

So, what is a progressive church? I think the best and most honest way to describe a progressive church is to describe it like an iceberg. There’s the part above the water you can see. There’s also the larger portion below the water that floats the rest.

The visible part of almost any progressive church of which I’m aware is, in 2023, a focus on LGBTQIA+ inclusion. This is essentially the litmus test for everything else. Progressive churches are likely to have well-placed rainbow flags on banners all over. Those joining the church are likely to prioritize LGBTQIA+ inclusion in their selection process as they choose a church. These are the churches LGBTQIA+ Christians previously excluded from religious community find their way back to (those who desire to do so, that is). And progressive churches are still really the only churches anywhere who overtly welcome LGBTQIA+ people not just as members, but also as pastors and leaders and teachers.

A few other social values circle around or near this LGBTQIA+ tip of the iceberg. In addition to inclusion, progressive churches are most likely among all liberal churches to align with the political Left, which is of course why some other Christians find them deeply problematic and (ahem) political. Because the wider culture simply assumes that Christians are conservative, any church that aligns with even some of the social or political values of the Left is going to be perceived as hyper-political simply because we break the gestalt. If you are moderately aware of the top priorities of the Left today, you can imagine progressive churches sharing commitment with them on these things: anti-racism work, some kind of economic safety net for everyone (socialism), environmental advocacy, women in leadership, diversity and inclusion, worker justice.

Progressive Christianity may be unique only in that it is willing to recognize and own, or at least strive to recognize and own, that faithfulness is continually a work in progress.

I list all of this not because I believe progressive Christianity should walk lockstep with the Left, but because it’s descriptively accurate. We share many values with the Left.

You might ask: Why? And isn’t that the co-optation of the church by the values of the world? Here’s where I try to home in on what I think it means to be a “progressive” Christian. I believe we call ourselves progressive Christians, and organize progressive church, because some parts of our shared life together in Western culture in the 21st century arise very naturally out of the gospel of Jesus Christ as it has been communicated through Scripture and the history of Christian life. I believe the gospel is “Left-resonant.”

For example, rather than thinking of socialism as “worldly,” as an outside force that is impinging on a supposedly co-opted pure “Christian worldview,” the first step in understanding the underpinnings of progressive Christianity is to accept that every set of beliefs has a history and has been formed by many forces. There is no “pure” Christianity. All Christianities have a social location.

So when many forms of conservative Christianity attempt to critique progressive Christianity as drawing too close to the culture, the main problem with this critique is the failure of those conservative Christians to recognize the ways in which they are also shaped by the culture—just other aspects of it, or the same aspects of it under a different guise.

Progressive Christianity may be unique only in that it is willing to recognize and own, or at least strive to recognize and own, that faithfulness is continually a work in progress. And (here we are going to the portion of the iceberg below the surface of the water) progressive church will live according to this admission, continually bringing the marks that center it (Scripture, tradition, etc.) into conversation with the experience and lives of those practicing it.

In other words, progressive church is about “progress,” but not necessarily in the sense that it believes in continual advancement or ascent, but rather as movement toward. This is what makes it essentially different from conservatism, which has as its impulse to conserve a heritage it often then stewards with self-deceiving nostalgia. Progressive Christianity recognizes it is likely we have gotten things wrong, that we continually get things wrong, that it is the work of the church to critically review its own way of being in the world and then strive to do better.

Vast swaths of Christians in the United States reject a secular movement that really ought to be, if considered, fully aligned with authentic Christianity. I’m thinking here of critical race theory (CRT). Critical race theory is, at root, simply a tool in academic life to pry open past practice and examine how those practices have been shaped by race and ethnicity. It’s like a secular parallel to the confession of sin. Yet somehow conservative Christians find critical race theory alarming. It’s as if they fear a clear-eyed examination of all our various complicities in systemic injustice. Admittedly, even I as a progressive Christian find the application of critical race theory discomfiting because I come to a greater realization of my own complicity in racism in the course of its application. And because I am discomfited, I will likely access some of the strategies I can muster, out of my own fragility, to resist the application of CRT.

Although I appreciate describing for readers the aspects of progressive church we already value and practice, I think it is more faithful and radically honest to admit that even those of us who inhabit progressive church space are still just figuring out what it is we’re even doing, and continually reforming and growing out of the interaction between the faith we hold and the experiences we continue having.

But what I won’t do as a progressive Christian is cease attempting to make progress on self-work and community work that can improve the lives of my neighbors, work that can make me a more faithful Christian. This is why anti-racism work is work. It’s an ongoing iterative process not of self-hate but of repentance. And critical race theory is one tool for that work.

As I have been trying out titles for this “progressive church guidebook” project, the other word I’ve been struggling with in the title is the preposition. Is this a guidebook “for” or “to” progressive church? If we say it is “for” progressive church, it implies I’ve already figured out how to do and be progressive church and I’m giving readers a tour of something that already exists.

On the other hand, if we say it is “to” progressive church, it implies instead that progressive church is something we are all continually on our way toward. What I write here serves as a way-post or a sign for all those on the journey toward progressive church. For this reason, although I also appreciate describing for readers the aspects of progressive church we already value and practice, I think it is more faithful and radically honest to admit that even those of us who inhabit progressive church space are still just figuring out what it is we’re even doing, and continually reforming and growing out of the interaction between the faith we hold and the experiences we continue having.

This invites two more simple insights about “progressive” church by way of introduction, topics we will return to in more detail. The first is the influence of liberation theology on progressive church practice. Even if many progressive churches are not engaged in liberative practices as profound as liberation theology invites, they nevertheless live sympathetic to the insights of liberation theology. That is to say, in their preaching and teaching they prioritize a “preferential option for the poor.” In liberation theology, “the poor” is both literal and figurative. “The poor” can include different groups in different contexts. In a state passing anti-trans laws denying health care to trans youth, the poor are trans youth. In places where the police oppress and harm African Americans, the poor are black lives. The point in all of it is that church from a liberation theology perspective prioritizes the lived experience of “the poor” and confesses that the gospel is living and active only if it offers a freeing and healing word specifically for “the poor.” This focus on “the poor” is not to the exclusion of the kinds of hopes prevalent in wider Christian culture (which I think center around getting “saved”) but rather is the neighbor-love corollary. It makes very little sense to prioritize or hyper-focus on an otherworldly salvation if in the meantime our poor neighbors are being left behind in the present. If you can imagine a form of salvation that offers you eternal life in Jesus when you die yet brushes aside prioritizing real life for all our neighbors (and the planet) in the present, then there is something inherently problematic with your soteriology.

The second point is more meta: One reason progressive church is still an unknown in many Christian contexts and unfamiliar to the wider culture is because it has been, to date, rarely tried. Many moderate and liberal churches certainly gesture at things like LGBTQIA+ inclusion. Far fewer actually practice it. As we often discuss in our church, there is a massive difference between saying to LGBTQIA+ Christians that they are welcome to come to “our” church, vs. saying together with LGBTQIA+ Christians in our community, “We’ve designed this queer space especially with you in mind.”

One of the most frequent questions I get asked in Arkansas is this one: Why is your church committed to LGBTQIA+ inclusion? Lately, I’ve been answering that question with a question: Why aren’t all churches? I’ve gotten tired of trying to rationalize something I think is self-evident. Presumably those asking me this question have been in contexts where it is self-evident Christians should exclude queer people. In other words, if I try to answer the question, if I try to offer a reasonable argument, in a way I’ve failed even before I’ve started because I concede the point that I must make the case for inclusion. But I think the reverse is true: all churches that exclude and condemn queer people (currently the majority) are the ones who should have to answer the question regularly and constantly: Why is bigotry a part of your faith?

Why aren’t all the inclusive Christians currently attending non-progressive churches not asking themselves and their leadership that question?

Rev. Clint Schnekloth is pastor of Good Shepherd Lutheran Church in Fayetteville, Arkansas, a progressive church in the South. He is the founder of Canopy NWA (a refugee resettlement agency) and Queer Camp, and is the author of Mediating Faith: Faith Formation in a Trans-Media Era. He blogs at Substack. This is the introduction to a larger book-length project. Access the entire “A Guidebook to Progressive Church” here.

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.