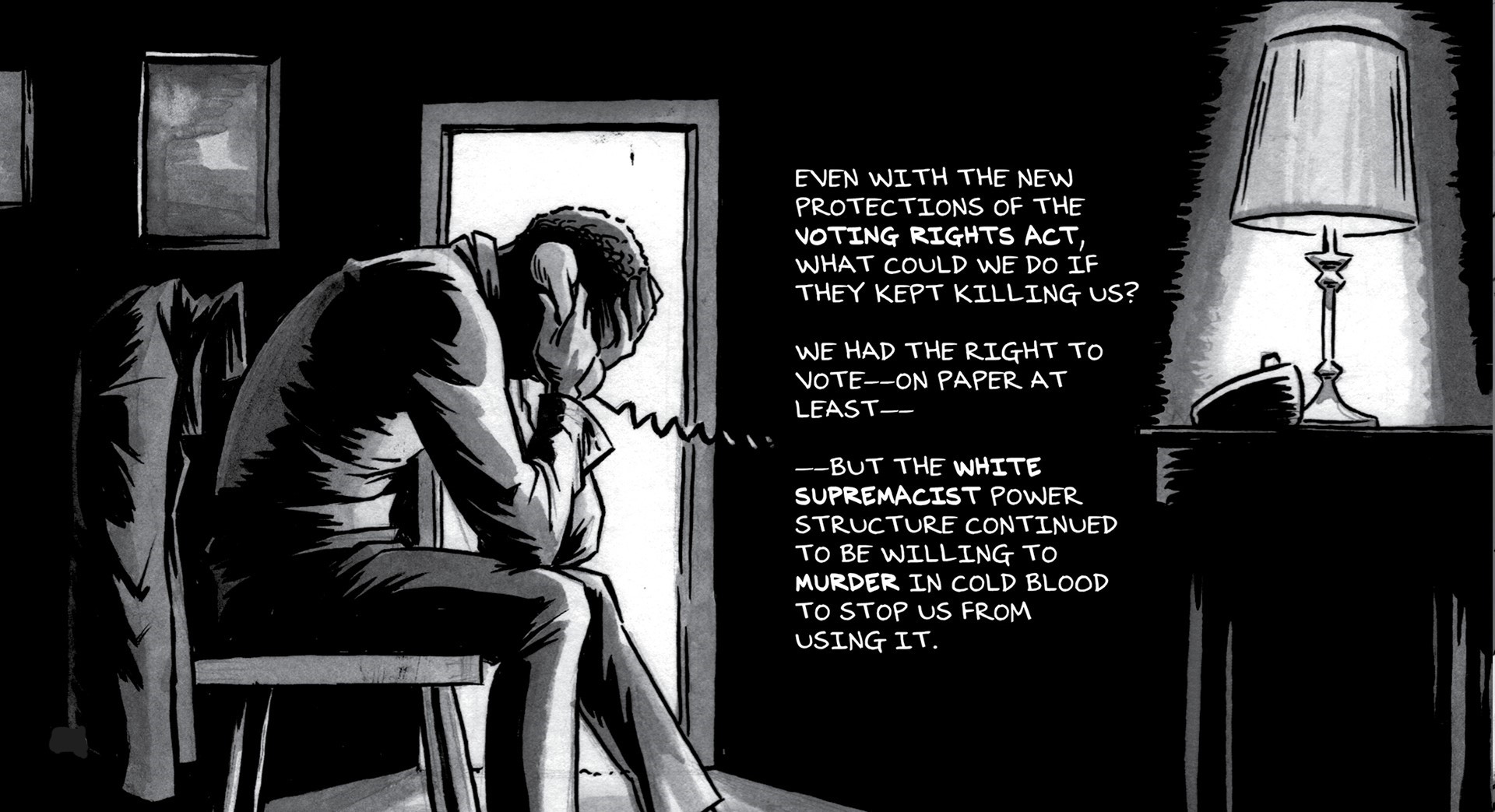

A young John Lewis on the telephone. From the graphic novel, Run.

Used by permission of Abrams.

A review of Run, the final graphic novel memoir of Rep. John Lewis

The March trilogy covers Lewis’ upbringing in Alabama in the Jim Crow-era South and the experiences that helped him grow into his own as a well-read and world-aware youth. By his late teens, Lewis was engaging with emerging Civil Rights-era leaders and activists on his way to become a great leader himself. Among his influences, Lewis credits a 1957 comic book, Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, published by the Fellowship of Reconciliation to reach more people with their advocacy of nonviolent strategies in the struggle for civil rights.[ii]

By the time of his death in 2020, Lewis was preparing the next chapter, entitled Run, Vol. I (Abrams ComicsArt, 2021). Joined by artists L. Fury and Nate Powell, Lewis and Aydin open in August 1965, as Lewis and others walk up to a church to join Sunday morning worship. They are immediately confronted by a church deacon, who orders them to leave. It is the third time this group visited First Baptist, Americus, Georgia, to join worship. Lewis turns to his compatriots and asks them to kneel in prayer.

By the time of his death in 2020, Lewis was preparing the next chapter, entitled Run, Vol. I (Abrams ComicsArt, 2021). Joined by artists L. Fury and Nate Powell, Lewis and Aydin open in August 1965, as Lewis and others walk up to a church to join Sunday morning worship. They are immediately confronted by a church deacon, who orders them to leave. It is the third time this group visited First Baptist, Americus, Georgia, to join worship. Lewis turns to his compatriots and asks them to kneel in prayer.

Within moments, police sirens blare, and multiple police cars arrive on the scene. The group led by Lewis are arrested for trespassing and taken away.

Meanwhile at the courthouse, a different scene is playing out. Surrounded by townspeople, members of the Ku Klux Klan have gathered in their regalia, ready to conduct their own march. The KKK Grand Dragon of Georgia bellows, “The Klan is the only salvation of the White Man other than Jesus Christ” (p. 7). With hearty Amens, the Klan then parades through town in broad daylight, with no resistance whatsoever.

Lewis narrates the moment: “The ink was barely dry on the Voting Rights Act, but already forces were gathering to fight back, using our own tactics. And America’s cities were ready to explode” (ibid.).

August 1965 is a powder keg itself, particularly in Lowndes County, Georgia. Lewis gives his ground-level experience as the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). While in top leadership, Lewis knew the path ahead—even within the movement—would be difficult. Lewis writes, “By the summer of 1965, most of the people who were with me in the early days—those who believed most deeply in nonviolence—had moved on” (p. 20). Increasingly, protestors argue among themselves about tactics, and more persons are at the ready to engage more physically in their resistance. Lewis finds his influence within SNCC slowly eroding.

While the Voting Rights Act became law, federal agents were more likely to “observe” than “enforce” at times. Organizing the vote was still a dangerous endeavor, and Lewis recalls the violence and lives lost. Lewis writes, “The Voting Rights Act brought new protections… and a desire among local young people to strike their own blows against injustice. But many black people in Lowndes County [Georgia] lived in fear. They knew one wrong move could get them killed” (p. 24). While the national coverage of the Watts Riots fills television screens across the country, the injustices of Lowndes County are plentiful, and the only certainty is each day’s passing brings more hardship and violence to those wanting to support voting rights and desegregation.

Death did rain down upon protestors and their allies. For example, after being bailed out of jail, a few SNCC members are cast out with no transportation to make their way back. They were ambushed by an armed man, who killed a young seminarian and wounded an Episcopal priest. The murderer would be eventually acquitted by an all-white jury.

Artists L. Fury and Nate Powell depict Lewis hunched over in grief after receiving the call. It has been only two days since Lewis was arrested with others trying to enter worship. Retelling the history, Run recreates the whirlwind of August 1965 and the mounting cost for these activists.

Lewis observes, “Even with the new protections of the Voting Rights Act, what could we do if they kept killing us? We had the right to vote—on paper at least—but the White supremacist power structure continued to be willing to murder in cold blood to stop us from using it” (p. 36).

Within SNCC, Lewis sees other, more strident voices coming to the forefront, and by the book’s conclusion, Lewis is replaced as SNCC chairman by Stokely Carmichael. One vote was taken earlier that night to reaffirm Lewis as chairman; however, another vote was called after many had left the room. During the second round of debates and voting, Lewis remembers “I didn’t say anything. I didn’t object. What was there to object to? There were no rules anymore. I could have simply left, but that’s not in keeping with the philosophy of nonviolence. I wasn’t going to hide” (p. 93).

Lewis’ words here are painful to read, watching a legend share such an unsettling moment that others may choose to leave out of their official autobiographies. Lewis was unreserved in acknowledging the scar on his forehead from when an Alabama state trooper fractured Lewis’ skull with a nightstick during the Bloody Sunday incident on March 7, 1965, at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma. Here, he shares his painful experience of having his leadership and personal integrity assailed, with Lewis resolved and resolute to stand by his non-violent principles.

Due to Lewis’ death in 2020, no further volumes of Run will be forthcoming. Readers of the March trilogy have this one extra volume, which leaves Lewis at his lowest point, leaving the SNCC offices with a box of possessions and little else. From a narrative standpoint, it seems an indefinite, tragedy-tinged ending if it were a work of fiction written to leave the reader at the uncertain edge. Nevertheless, as you turn the page, Lewis adds this coda about what is yet to come.

Standing on the street, in the rain, Lewis looks out on the world beyond the SNCC office. He writes, “I thought about going home to Pike County, but I couldn’t do that. It felt like giving up. At moments like this my mother would say ‘Put it in the hands of the Lord,’ so I did. And when a new life in a new city presented itself to me, I ran.” (pp. 114-5).

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.

[ii] For more on this early comic, visit

https://www.learningforjustice.org/magazine/spring-2015/martin-luther-king-and-the-montgomery-story.

Also, at the end of the Run graphic novel, the authors and artists provide historical notes about their choices retelling and depicting the history covered in Lewis’ memoir. It will help guide readers less familiar with the personages and key events depicted throughout the book.