A Sankofa confession: Reflections of an emeritus pastor on prophetic preaching

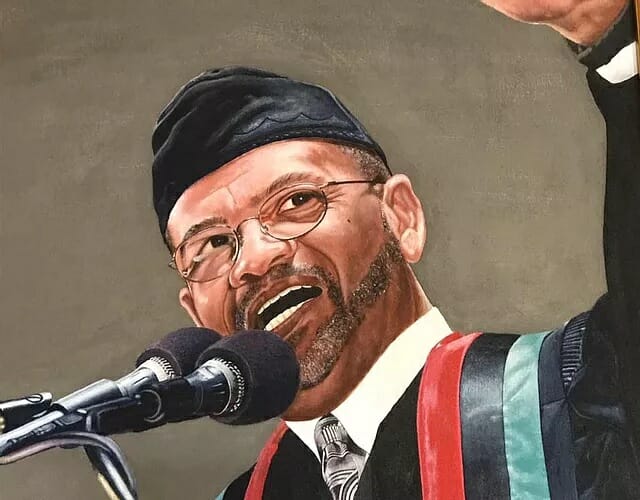

Dr. J. Alfred Smith, Sr.

June 9, 2021

God has richly blessed me in pastoral ministry, and much more than I deserve. As a young student serving churches whose members patiently listened to me before I knew the difference between eisegesis and exegesis, I thought that I was a good preacher because of their affirming verbal responses. Though they paid me a meager salary, it was much more than what I deserved.

These Missouri churches—Mount Washington Baptist Church in Parksville, Ebenezer Baptist Church in Armstrong, and Second Baptist Church in Huntsville—were filled with sacrificial givers who could not pay a full-time salary for my service. Second Baptist’s payment was a mixture of cash, a parsonage, and groceries from the members’ gardens and meat stalls. At times I supplemented my modest salaries by working in the Missouri hay fields, and by teaching in a two-room, segregated school for black children.

In retrospect, I was preaching to small churches composed of marginalized, oppressed people before I had even discovered my preaching voice. I depended upon the members to support my fragile ego much more than I preached sermons that would help them navigate living in that part of Missouri, known as “Little Dixie.” However, I struggled to preach motivational, topical sermons. Rather than being expository in nature, the sermon texts often served as props for the topics, rather than the topics drawing their essence from the texts.

Upon being called to serve full time as pastor of the Second Baptist Church of Columbia, I was drafted to work with the Missouri state NAACP to facilitate the desegregation of the public schools. During this time, my approach to social justice preaching was based on my seminary studies of the historical Jesus and the 8th century prophets. These sermons fell short in emphasizing power issues based on equity and the inclusion of blacks in determining how school desegregation would be accomplished. For instance, I needed to condemn busing, which was purported to achieve equity, but which was never understood to be a two-way course of action that would allow black and white children to be bused into each other’s residential communities. Instead, busing was a one-way system that bused black children into white communities, implying that white children had nothing to gain by being bused into black communities. Another way that I could have exposed power issues would have been to point out that teaching positions were not assured for black educators whose credentials matched those of their white counterparts.

Sadly, the black pulpit—not the white pulpit—was enlisted to preach for peaceful acceptance of desegregation on the terms decided by the white power structure. Thus, the black pulpit was often resigned to a pseudo preaching about justice. Black church members were not the stakeholders, not the decision makers. Whites—if they attended any church—occupied these important positions, and among many of them white supremacy was taken for granted.

I became the pastor of the Allen Temple Baptist Church in Oakland, California, shortly after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. In Oakland, the Black Panther Party had become the prophetic voice of the black community, along with other activists, all of them following in the tradition of earlier prophetic voices like that of Malcolm X. These secular advocates were independent of the influences of white religion. Instead, they were influenced by the Harlem Renaissance poets and artists, and by later writers and artists such as James Baldwin and Billie Holiday. Unforgettably, Miss Holiday recorded the provocative song, “Strange Fruit”: “Southern trees bear a strange fruit / Blood on the leaves and blood at the root / Black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze / Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.”

At a time when the content of the black pulpit was seemingly unheard, a young theologian named James Cone emerged and called the academy and the church to task with his writings in “God of the Oppressed” and “The Cross and the Lynching Tree.” In the latter book, Dr. Cone offered an alternative to the traditional understandings of Calvary. In line with him in today’s academy are voices that speak truth to power, such as Cornel West, author of “Prophesy Deliverance! An Afro-American Revolutionary Christianity,” and Michael Eric Dyson, author of the prophetic book, “Long Time Coming: Reckoning with Race in America.” After some forty-two years, the classic work on prophetic preaching, “God in the Ghetto,” by pastor-scholar William Augustus Jones, has been reissued by Judson Press. Also, let us not forget the powerful sermons of C.L. Franklin (“Can These Bones Live?”) and Charles Gilchrist Adams (“Drunk on the Eve of the Reconstruction”).

I am not sure if many preachers today know what constitutes prophetic preaching. Some may believe it is speaking six feet above contradiction. Others may aver that it is speaking truth to power by inveighing invective against political power structures. But railing in the pulpit against power structures is merely preaching to the choir. These sermons are not heard by Fox News and the reactionary community that supports American exceptionalism and white Christian nationalism.

Being truly grateful to God most merciful and kind for a fruitful and satisfying ministry, my desire is to be a friend to younger men and women in Christian ministry, and to encourage them and hold them up in prayer so that they may reach their potential in Christ, balancing their prophetic and priestly roles.

Still some other preachers forget that the 8th century biblical prophets balanced both the priestly and the prophetic. Among the writing prophets, Jeremiah and Ezekiel were priests and prophets. And the non-writing prophets such as Huldah, Deborah, Nathan, Elijah, Elisha, and Micaiah spoke the ethical and moral truth of God in their role as moral guides of the disobedient masses. Ezekiel not only addressed the immorality and idolatry of the kings and the sins of the nations, but spoke of the penalty of personal immorality when he declared that “the soul who sins shall die” (Ezekiel 18:20 NKJV).

While it is imperative to preach against systemic racism in police departments, prophets do not forget to preach against neighborhood gang fratricide in which people kill their own kind. Prophets call all people back to God and away from the idols of nationalism, materialism, hedonism, militarism, racism, sexism, ageism, ethnocentrism, and every other sin. Prophets are not single-issue minded.

Now, as a pastor emeritus, when I reflect on more than a half-century in service as a local church pastor, I recall striving to balance the prophetic and priestly roles. I am certain that at times I overplayed my prophetic role in speaking six feet above contradiction, and underplayed my priestly role of being the bridge between people and their sacred intimacy with The Eternal.

Let us pray for pastors in the difficult struggle of balancing the prophetic and the priestly. Among several on my prayer list is a non-Baptist role model whom I mention while also revering my deep relationships with Baptist friends. I speak of The Reverend Doctor William Barber II, senior pastor of the Greenleaf Christian Church in Goldsboro, North Carolina. His ministry flows from a theological understanding of balancing love, justice, and power.

I thank God for Daddy Jeremiah Wright Jr. and his spiritual son Dr. Frederick Douglass Haynes III.

I thank God for my pastor, Dr. Jacqueline Thompson.

I thank God for Dr. Gina Stewart, Dr. Otis Moss III, Dr. John Howard Wesley, Dr. Warren Stewart, Dr. Claybon Lea, and youthful Pastor Brian Hunter, among others who help me to see areas where I could have improved my skills before becoming an emeritus pastor.

I do not speak six feet above contradiction. Therefore, being truly grateful to God most merciful and kind for a fruitful and satisfying ministry, my desire is to be a friend to younger men and women in Christian ministry, and to encourage them and hold them up in prayer so that they may reach their potential in Christ.

Dr. J. Alfred Smith, Sr., is pastor emeritus, Allen Temple Baptist Church, and professor emeritus, Berkeley School of Theology (formerly American Baptist Seminary of the West, Oakland, California.

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.