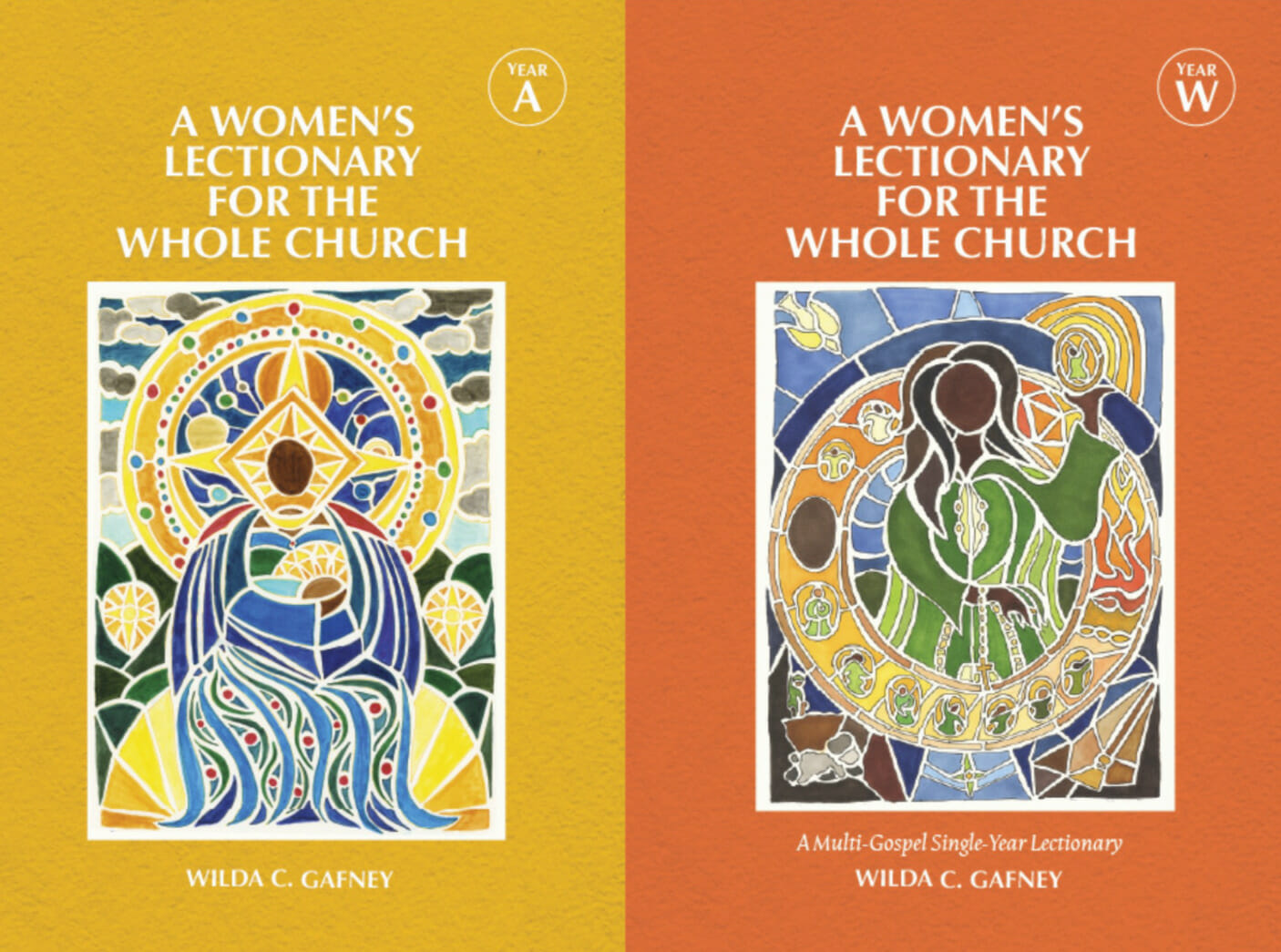

Image by Rev. Wilda C. Gafney, Ph.D.

“A Women’s Lectionary for the Whole Church,” Year W and A (Review)

Among American Baptists, we reflect the wider Baptist tradition in the high value of the sermon as part of the worship service, even considered by many as the central feature, if not apex, of an order of worship. While style and delivery may differ, the biblical text is the focal point, and many of us endeavor to do justice to God and the Word, even as we find ourselves wrestling with reflecting and writing, often at a long stretch of week after week after week.

For some American Baptist clergy, the use of the Revised Common Lectionary is a familiar tool. For other colleagues, the Scripture texts are chosen more at the discretion of the preacher, sometimes organized into themes and series over a period of weeks. In my own ministry, I have followed the weekly readings suggested by the RCL, though I have strayed when the congregation needed a different word when events (local or global) necessitated a prayerful detour elsewhere into the sacred texts to make sense of pain, anxiety, complexities, or disruptive moments happening within and well beyond the fellowship. The RCL provides one form of guidance. Pastoral attentiveness to sacred text and congregational context provides another.

The RCL is organized into three years, labeled as Year “A,” “B,” and “C.” Each Sunday, the pastor and worship planners have four readings, drawn typically from the Gospels, the epistles, the Psalms and the Hebrew Bible. Often, many pastors will settle on one or perhaps two of these texts and weave together a sermon. (I say “weave” optimistically, as sometimes the writing of a sermon is more like untangling a ball of yarn somewhere between your brain and the blank page staring back at you on the computer screen.)

Since the RCL was first revised and published in 1992, it has been used in a variety of Protestant and Roman Catholic traditions with regularity and variance as noted above. Certainly, any attempt short of “read the Bible in one year” type plans will be unlikely to include the full reading of Scripture if one depends solely on the fifty-two Sundays of a year and the need to read Scripture and provide a sermon of reasonable length and still make it home before the pot roast is found charcoaled in the oven. (I note this latter observation thanks to my mother, who reminded her neophyte preacher son to remember to keep it short enough that the dinner left cooking or simmering at home stands a chance of being enjoyed!)

More serious critique has come from the many preachers and scholars who have pointed out the editorial approach to the Scripture readings sometimes shortchanges the experience of reading and hearing the fuller text. The readings often truncate the Psalm readings to the point some of the pathos of the individual Psalm is edited out in the suggested reading. Many Christian preachers will emphasize the Gospel or Epistle reading to the detriment of hearing more of the Hebrew Bible. No reading strategy of the canon of Scripture is perfect, and being aware of what choices we make as preachers is helpful for honoring the fullness of biblical texts as well as helping listeners engage with texts and teachings that the Lectionary, even in earnest effort, leaves aside.

With this new lectionary year approaching with Advent soon at hand, preachers have an additional resource to consider in planning their worship and sermons. From Church Publishing, a new series, “A Women’s Lectionary for the Whole Church,” published its inaugural volumes earlier this year.

The project of Dr. Wilda C. Gafney (Hulsey Professor of Hebrew Bible, Brite Divinity School, Texas Christian University), this lectionary series appears in two versions. One is the three-year cycle named A, B, and C, yet not the Scripture readings suggested by the RCL. Instead, Gafney sets new combinations of the readings to refocus preaching and shift the conversations lectionary readings spark in the hearts and minds of the congregation regarding issues of gender and the gulf between more equitable practices for women and how the Church has tended to operate otherwise.

The second is a stand-alone Year W (“W” for Women), arranged for those who do not follow three-year cycles yet have interest in engaging the texts and the issues she raises about those voices less represented or overlooked entirely due to biases from prior lectionary efforts.

Along whichever multi or single year path is chosen, Gafney offers insights into Good News preaching that is also a liberating word for women, girls, and the whole Church with more focused engagement that dismantles gender-bound structures within church and society alike. The volumes for Years W and A are now available for purchase. The B and C volumes will be published in 2022-2023.

With the new lectionary year approaching with Advent soon at hand, preachers have an additional resource to consider in planning their worship and sermons. A new series, “A Women’s Lectionary for the Whole Church,” by Dr. Wilda C. Gafney, published its inaugural volumes earlier this year.

All four volumes offer congregations the opportunity to hear the Sunday readings in a new light, focusing on the issues often omitted by previous RCL resources and questioning interpretations that omit, overlook, or oppress women and their roles in the biblical narrative and subsequently church history and the present day. Gafney notes the Hebrew Bible alone references “at a minimum one hundred and eleven named women”[i] in the texts and many more unnamed women and girls. She has encountered many in classrooms and congregations who struggle to name even one woman from the canon of Scripture. Further, she observes that the available lectionary cycle readings “do not introduce us to a tithe of [the women named or unnamed in the Bible]. As a result, all many congregants know of the Bible is the texts they hear read from their respective lectionary.”[ii]

The Year W lectionary follows a one-year cycle of Gospel readings aligned with the main liturgical seasons and days common to many mainline Protestant and Roman Catholic church years. For example, the Year W volume’s four Sundays of Advent provide an alternative path to the passages used more in the RCL Advent cycles that speak to the eschatological waiting for the Son of Man before moving into the prophetic witness, while wending the way to the most familiar Nativity narratives at Christmas Eve/Christmas Day.

A lectionary resource is best evaluated through practice. If the preacher chooses the one-year W or a volume of the three-year set, they will find Gafney’s textual and homiletical insights quite helpful, reorienting our awareness of issues of interpretation and uplifting the Word through each week’s format of text notes on the readings and the “preaching prompts.”

Often prophets and patriarchs figure in our memory of sermons, Bible studies and Sunday school. Gafney’s long-form engagement with the lectionary shows there is much fruit yet to be heard of women named and unnamed in the text and their faithfulness before God in a world where patriarchy and violence, inequality and gender exclusive practices are still well embedded in the present as well as the past.

Preaching with Gafney’s lectionary aids may provide a new sort of companionable presence to the pulpit and the pews alike: hearing, listening and reflecting on the God/human relationship with sensitivity to issues often overlooked or considered too difficult to discuss. One might ask after spending time following the Year W lectionary how their preaching has changed, as well as what new issues vex and challenge the pastoral imagination as it plays out in the ministry between Sundays with pastoral care, discipleship training and engaging local needs.

For example, the first Advent readings pair the angel’s annunciation to Mary (Luke 1:26-38) with that of Hagar out in the desert (Genesis 16:7-13). (The other texts Year W recommends that Sunday are Psalm 71:4-11 and Philippians 2:5-11.) Reading these texts on the first Sunday of Advent draws us closer to the human side of the Scriptures, speaking of pregnancy and motherhood in adverse circumstances and demonstrating women who have obedience and agency in these divine encounters, as Mary consents to the word announced by the angel and Hagar, cast into the margins by a jealous Sarah, names God Elroi out of her encounter with God in the desert. In seminary classrooms, we hear about Hagar and her naming of God, yet many students express new acquaintance with Hagar’s story in the Abraham and Sarah narratives. In local congregations and their communities, we are surrounded by opportunities to serve in the name of Jesus with single and young mothers, children whose lives are shaped by adversity at a young age, and families and society in need of transformation into better and just existence for all persons.

Why not bring less familiar yet deeply powerful biblical texts into the midst of a season where we need a word of promise and hope?

Rev. Jerrod H. Hugenot is associate executive minister, American Baptist Churches of New York State.

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.