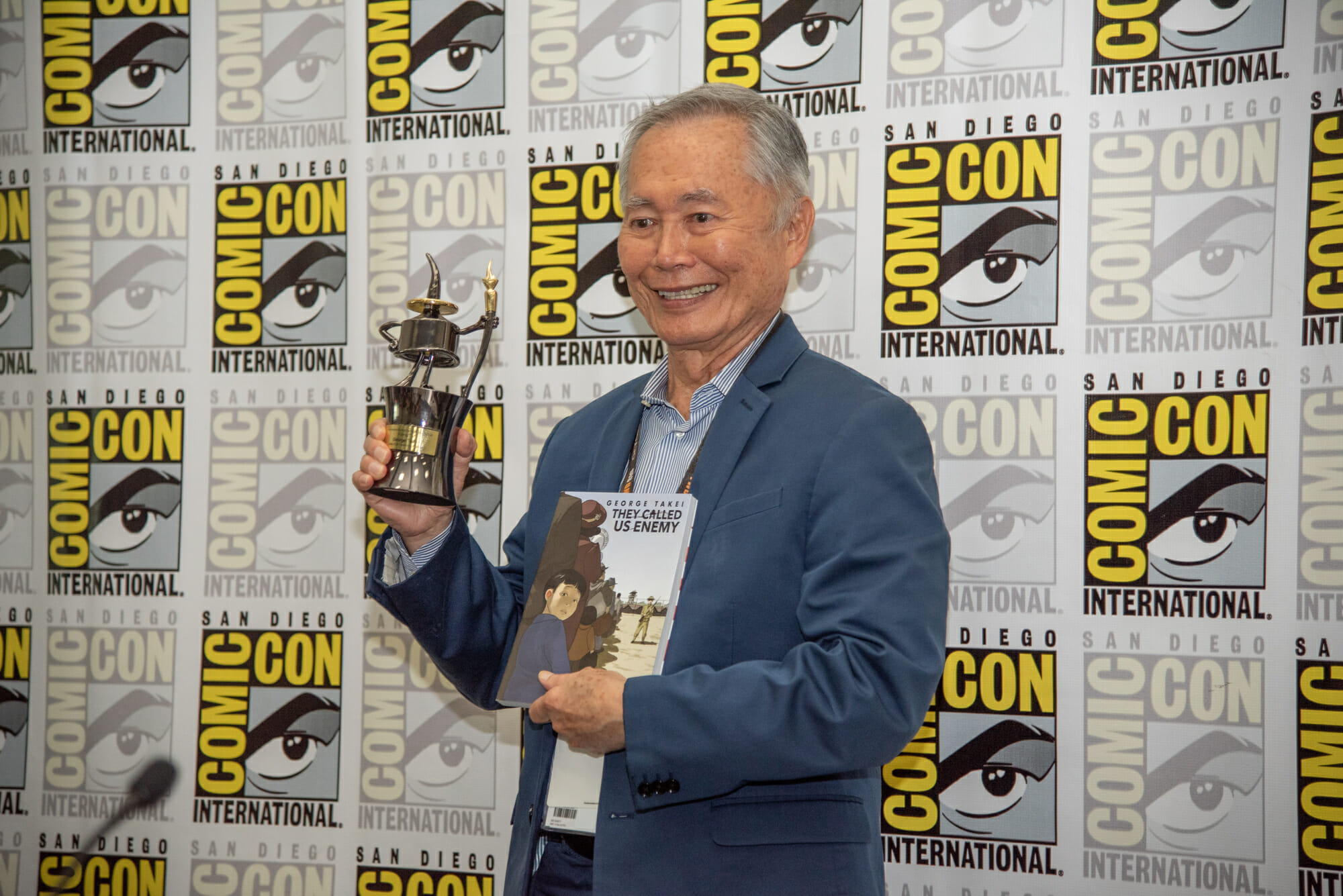

Actor and activist George Takei’s graphic novel reclaims history

Rev. Jerrod H Hugenot

September 24, 2019

Actor and activist George Takei is a highly visible person in American pop culture—and in recent years, social media. In part, he has used this public profile to tell of his experiences growing up in the United States, particularly through the lens of his earliest years being among the many who were interned during the Second World War. The title of his new graphic novel memoir states this plainly: “They Called Us Enemy.”

Actor and activist George Takei uses his public profile to tell of his experiences growing up in the United States, particularly through the lens of his early years being interned during the Second World War. Most recently, Takei tells this story through his new graphic novel, “They Called Us Enemy.”

© George Takei, courtesy Top Shelf Productions

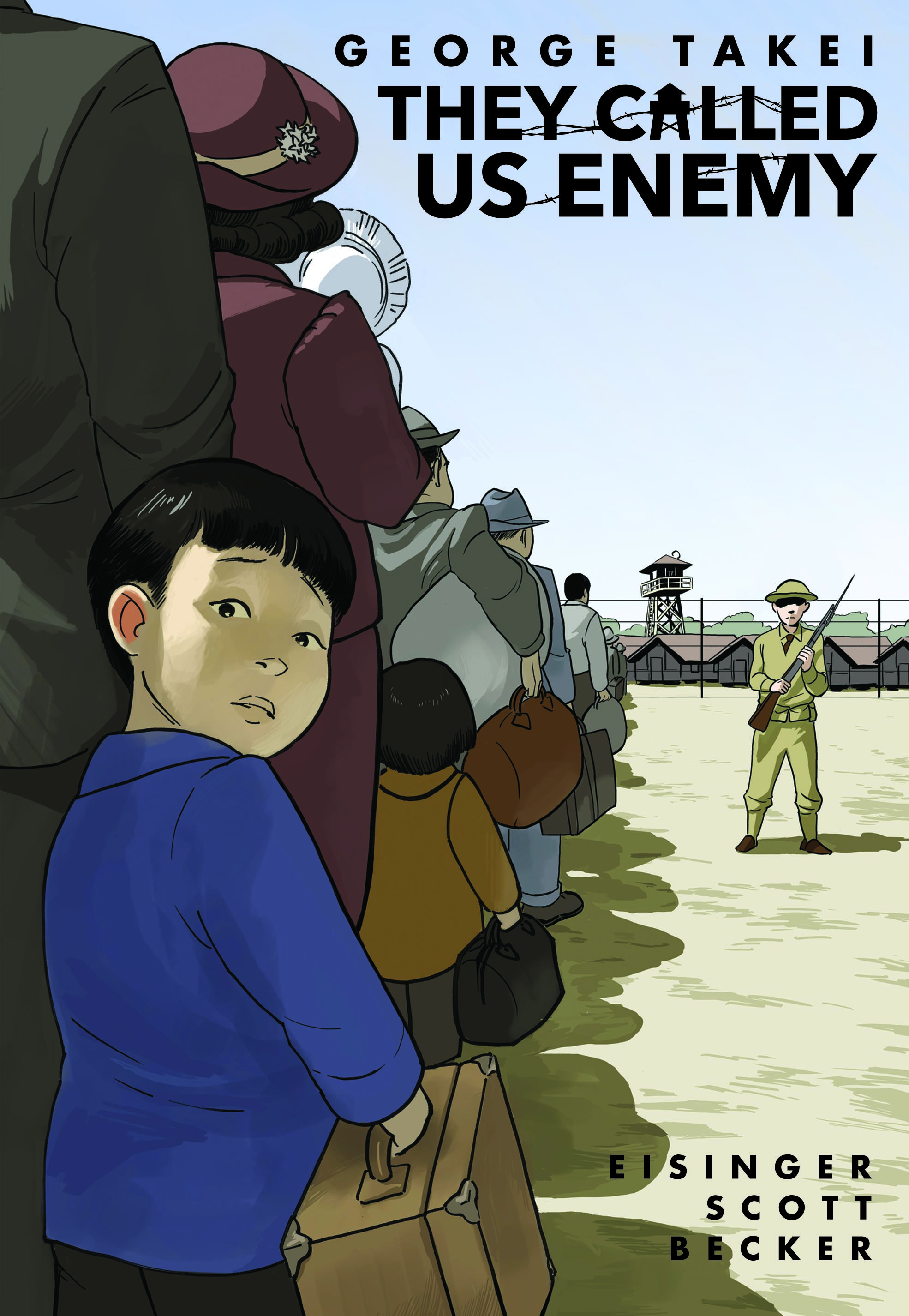

The graphic novel (IDW/Top Shelf Productions, 2019) is the latest of many ways Takei has brought to light the stories of Japanese and Japanese Americans who were given notice to leave their homes, personal possessions and livelihoods, and then taken to makeshift staging areas and barracks to be processed, then shipped across the United States to an internment camp. Takei’s family was sent from California by rail to a camp in rural Arkansas. Taken from their family home, the Takeis ended that fateful day being shown to a conscripted racetrack’s horse stables for temporary housing. Later, when they reached Arkansas, they were crowded into camp barracks where very little dignity and privacy was afforded, all surrounded by barbed-wire fencing.

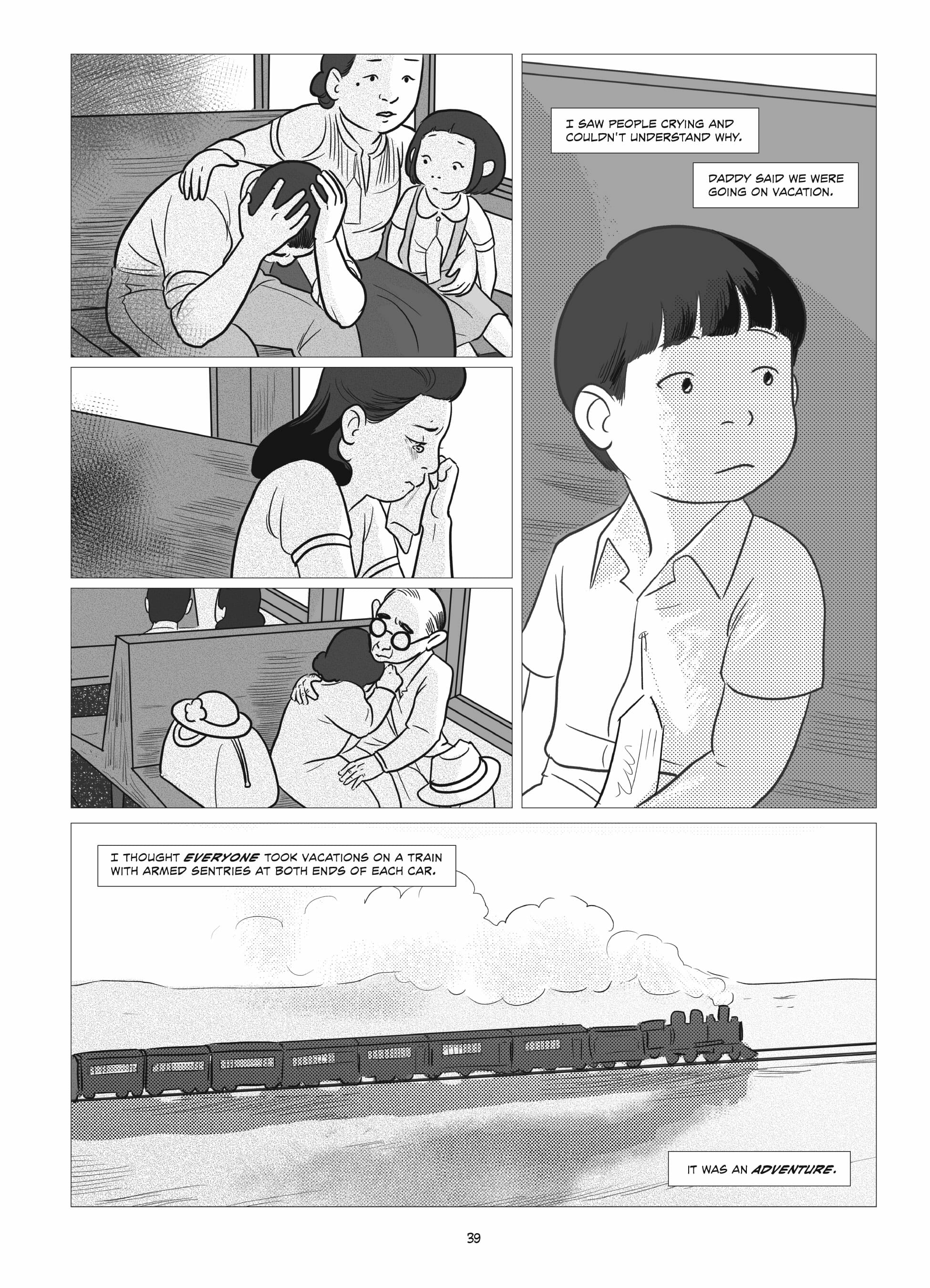

(Life in the California racetrack stalls is echoed by American Baptists recalling their own internment experience. View this testimony as part of the ABHMS video “A Church Stands With Its People,” available here). The graphic novel medium lends itself to sharpening the drama in Takei’s recollections. A two-panel page depicts above the family arriving at the temporary housing early in their journey. The parents look taken aback as young George, clutching a suitcase, excitedly proclaims, “We get to sleep where the horsies slept! Fun!” Looking back decades later, Takei reflects, “Each family was assigned a horse stall still pungent with the stink of manure…. As a kid, I couldn’t grasp the injustice of the situation.”

Filtered through the lens of a child, this seemed a vacation or an adventure. The experience of internment camp life is retold in short scenes… Takei’s father becomes a recognized leader within the camp, organizing arriving strangers from all over the country into a more communal identity, particularly when it came to mediating challenging moments within the internment camp.

The page’s lower half-page panel depicts the shock and apprehension of his parents. The father looks dumbstruck, the mother holds an infant and tries to hold back her own emotions as she hears her eldest ebullient about the stable. George Takei’s narration accompanies with: “But for my parents, it was a devastating blow. They had worked so hard to buy a two-bedroom house and raise a family in Los Angeles…. now we were crammed into a single, smelly horse stall. It was a degrading, humiliating, painful experience.”

The family fell under the provisions of Executive Order #9066, which called for “the conduct and control of alien enemies,” issued in the wake of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. While that attack was one of infamy, the actions of FDR and the US government were later acknowledged by President Ronald Reagan as a time when the U.S. should “admit a wrong,” signing legislation in August 1988 so that the nation may “reaffirm our commitment…to equal justice under the law.” Longtime American Baptist and a camp internee Yosh Nakagawa shares his own experience under #9066 here.

Filtered through the lens of a child, this seemed a vacation or an adventure. The experience of internment camp life is retold in short scenes. Takei’s mother found materials to use with her sewing machine (somehow miraculously smuggled into camp after a cross-country railway journey) to create domestic normalcy (drapes, rugs, etc.) Takei’s father becomes a recognized leader within the camp, organizing arriving strangers from all over the country into a more communal identity, particularly when it came to mediating challenging moments within the internment camp.

In another scene, young George is encouraged by older boys to shout at the guards to get candy. Then they tell him a particular word to use to get their attention. Even though the graphic novel is a static medium, I felt the tension build within me as I realized what George did not. He was being set up and possibly even in danger of being harmed or killed, once he shouted a phrase that would have possibly enraged the armed guards. He did not come to harm, thankfully!

Takei and his team of writers, with the illustration of Harmony Becker, craft a narrative that slips between the WWII era and the present day, with asides as Takei recalls key moments in his life after the family was able to return home, though to more of a skid row-type setting with no funds to restart their lives. Takei grows up, becoming interested in performing. His father also encourages him to get involved in the civic process, stressing the importance of democratic involvement (even as the Takei family experienced what they did). Takei does note that many textbooks published after WWII did not mention anything of his family’s experience in the immediate years thereafter.

© George Takei, courtesy Top Shelf Productions

As a young adult, Takei will meet Eleanor Roosevelt when she stops by a campaign office to meet the workers, but only later does Takei realize that his father left for home, feeling unready to meet any Roosevelt. His father would not live to see Reagan’s press conference, acknowledging the US government’s need to “right a wrong,” nor receive the letter and reparation check sent to internee survivors under the first Bush administration. Years later, Takei would speak at the FDR Estate in Hyde Park, NY, speaking about these experiences on the 75th anniversary of Executive Order #9066 being issued. He also staged a Broadway musical called Allegiance, retelling the story of a camp family internment.

In these moments, we see the wrestling with history that leads to more truthful understanding of the nation’s past. Releasing this graphic novel in mid-2019, Takei and his team also reflect on the similar images of persons interned by the government, this time from the perspective of the border crisis still ongoing.

A later page, also subdivided into two half-page panels, has Takei’s observation of national events happening in January 2009 and June 2018. He says, “And while in my lifetime I’ve come to see the ideals [my late father] taught embraced with conviction, old outrages have begun to resurface…with brutal results.” The artist depicts a moment from Barack Obama’s 2009 inaugural address above with the lower panel of a crying child, hand on the fence, looking back at the reader amid people interned at the US/Mexico border in conditions we increasingly hear from observers and members of Congress are substandard at best. Takei’s earlier memories of a horse stall come back, along with his words from an America decades ago, “It was a degrading, humiliating, painful experience.”

I encourage you to read this book, regardless of your age or any preconceptions you might have about such a story coming in graphic novel form. Indeed, in recent years, the publisher had great success working with Representative John Lewis, whose Civil Rights experiences form the graphic novel series March. Like the earlier Lewis trilogy, Takei’s book brings the past to a new generation, particularly now as we are over-saturated with images from the border and polarization politically about how to resolve legislation and enforcement. Our past has much to instruct us, especially when we are in a season of yet again declaring persons the other, the unwelcome, or somehow our “enemy.”

Rev Jerrod H. Hugenot is the associate executive minister of the American Baptist Churches of New York State.

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.