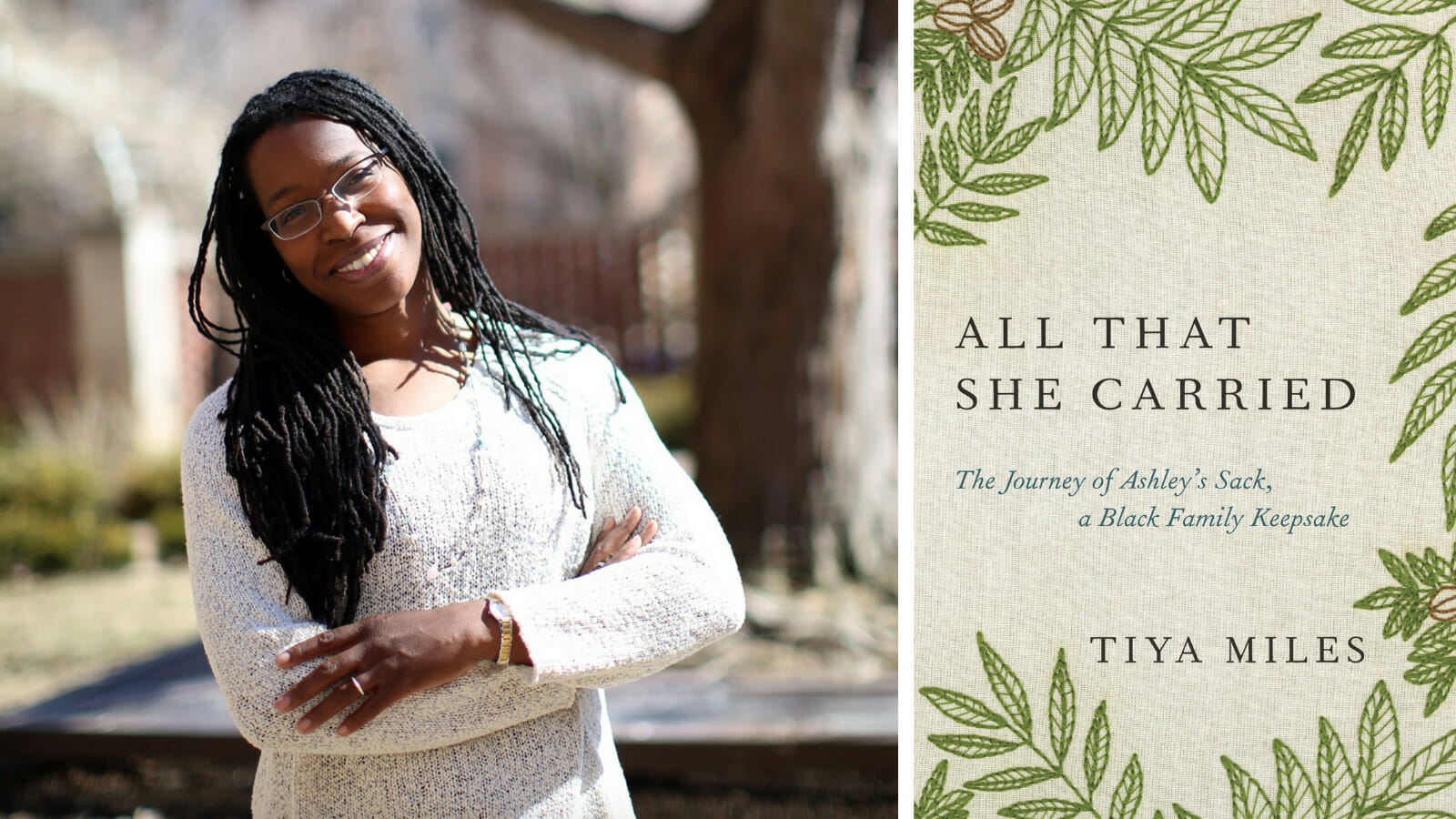

“All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake” (Book review)

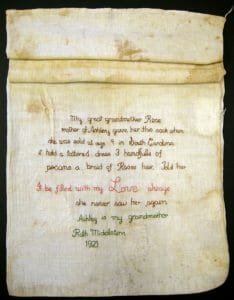

In past years, visitors to the National Museum of African American Heritage and Culture, part of the Smithsonian Institution in our nation’s capital, discovered among its many items on exhibit an old, stained cotton sack. The visitors lingered, taking in the words embroidered on the fabric:

My great-grandmother Rose

mother of Ashley gave her this sack when

she was sold at age 9 in South Carolina

it held a tattered dress 3 handfulls of

pecans a braid of Roses hair. Told her

It be filled with my Love always

she never saw her again

Ashley is my grandmother

Ruth Middleton

1921

Smithsonian curators soon realized that the display needed tissue boxes on hand for visitors, as the sack and its brief words captured the pathos and perseverance of those it accompanied down the generations.

In 1921, Ruth Middleton embroidered this cotton sack with a powerful family story. Middleton Place via Wikimedia Commons under public domain.

Ashley’s sack records just a moment of a longer story, moving from antebellum America to the era of the Great Migration, as Ruth Middleton embroidered the fabric of her family history into the rough cotton cloth sack, which had been passed down as a keepsake of perseverance, despite the odds. While slavery would be abolished, the failures of the Reconstruction Era and the pivot to entrench Jim Crow laws created no great easing for Rose’s descendants, yet the sack bore witness to Ruth (by then living in the North as part of the Great Migration) that her family’s history was remarkably resilient.

How do we prepare for the uncertainty at hand yet retain the “radical hope” for the future? Miles writes, “Our only options in this predicament, this state of political and planetary emergency, are to act as first responders or die not trying. We are the ancestors of our descendants. They are the generations we’ve made. With a ‘radical hope’ for their survival, what we will pack in their sacks?”

In her recent “All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake,” Harvard historian Dr. Tiya Miles writes, “In the face of the base commercialization of their own bodies, these Black kinswomen cared for one another, preserving the next generations by provisioning their perseverance and remembering the past generations who defended their right to life.”[i]

Ashley’s sack became an act of love in the face of the inhumanity of the enslavers, and it served as an emergency pack for Ashley’s uncertain path ahead.[ii] Drawing on a line from Octavia Butler’s “Parable of the Sower,” Miles invites her readers into the in-depth historical research she called upon to understand this story of Rose, Ashley, and the sack that bound generations together. She also challenges the reader to look at this story as a guide for the times at hand, with the racial and political divides framing the past two years. How do we prepare for the uncertainty at hand yet retain the “radical hope” for the future? Miles writes, “Our only options in this predicament, this state of political and planetary emergency, are to act as first responders or die not trying. We are the ancestors of our descendants. They are the generations we’ve made. With a ‘radical hope’ for their survival, what we will pack in their sacks?”[iii]

Of the embroiderer and descendant Ruth Middleton, Miles writes, “With cloth as surface and embroidery thread and needle as tools, she framed this survival tale as a women’s story, claiming the feminine space for her foremothers and for herself at a time—in the early 1900s—when the value of Black womanhood was still widely denigrated in American society. She must have shared a sense of the cross-cultural symbolism that fabric carries as a metaphor for tying, weaving, knotting, and biding people together.”[iv]

Through each chapter, Miles unfurls an otherwise tangled and sometimes fragmentary history, locating where Rose and Ashley’s story began in 1850s South Carolina. Miles notes, “While these pages will offer grounded interpretations based on evidence, comparison, and context, they will also accommodate supposition and imagination, recognizing that there are a great many things about the past that we cannot know for certain, especially with regard to populations whose lives were mostly under recorded or misunderstood.”[v]

Miles works through records and other sources to situate Rose as enslaved by one Robert Martin, upon whose death the estate was inventoried and valued (slaves included alongside other property), setting in motion Rose’s efforts to provide for her daughter before Ashley was sold away from her.[vi] Chapter by chapter, Miles goes through the items of the sack, bringing to life a narrative of survival otherwise less understood. Of the power of Rose’s love and care in creating the sack, Miles observes, “Twined with a mother’s love, the fabric of kinship sustained the wear and tear of slavery’s assault.”[vii]

For example, in her chapter on the “3 handfuls of pecans,” Miles shows the deeper meaning of Rose’s care for her daughter. Pecans were not yet that easy to obtain in 1850s America, so Rose’s provision of them points to great care for her daughter and access to the household’s kitchen as a cook.[viii] Miles ponders if the pecans were for nourishment or perhaps the care taken to equip Ashley for the future, a seed to plant and a gift that could produce yields long into the future.[ix]

Further, researching the history of pecan production, Miles recounts the story of an enslaved man named Antoine, who in 1846 Louisiana was the first successfully to graft “16 trees, which he extended into a healthy orchard of 110 trees.”[x] Antoine’s part in creating an economic boon still continuing today for American producers is less recalled and credited, yet another reason “history” is deeply political and always in need of honest revision and even humility in its telling.

While others have written about Ashley’s sack and its historical relevance, the approach of Miles’s scholarship is remarkable in the juxtaposition of her supposition and imagination, along with the research sources and tools used. This is one of those rare books that I do not know if I will ever consider “read,” as rereadings of Miles’s work keep engaging me with return visits.

Rev. Jerrod H. Hugenot is associate executive minister, American Baptist Churches of New York State.

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.

[i] Tiya Miles, “All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake,” (New York: Random House, 2021), 7.

[ii] Miles, xiii.

[iii] Miles, xvi–xvii.

[iv] Miles, 234, emphasis original.

[v] Miles, 17.

[vi] Miles, 68ff.

[vii] Miles, 189.

[viii] Miles, 196.

[ix] Miles, 195.

[x] Miles, 200.