Black theology—a radical view

At times a radical view is not only unique and uplifting but essential. In the 1960s, Black theology emerged as a radical view. It was radical because it departed from the ivory halls of academia as a theology forged out of American oppression. Theological studies in America had been steeped in Western Christianity, one of privilege and power. This same theology was taught to Black seminarians. As a seminary graduate myself, I can imagine how challenging this was. Learning theological concepts written and exposed by white men of privilege and prejudice and not hearing a theological perspective that spoke from oppression of Black America was another form of oppression. This situation caused tension between what was taught and reality.

The 1960s was the culmination of unrest over centuries of oppression. Black America had been pushed to its breaking point. The civil rights movement had developed a powerful following, grassroots organizations were springing up to resist the status quo, and change was in the air. The Black Power movement caught the hearts of many African Americans and the attention of white America. America may not have expected what would come out of this crucible of unrest—the birth of an authentic theology. We understand theology in its simplest form as the study of God. Christian theology is the study of God from the Christian tradition. While Christianity has its roots in Judaism, Western Christianity is a form distinct to America. American Christian theology may have presented a benevolent God, yet it presented a God who sided with the oppressor. This was seen even before there was a formal theological voice speaking of and from the oppressed. Africans in slavery were noted for saying there must be two heavens—“The master is having his heaven now, and we will have our heaven when we die.”

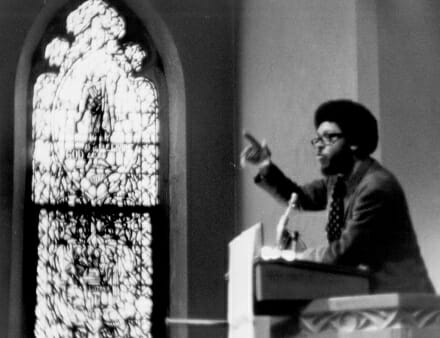

As civil rights protests increased, riots exploded across the country and Black clergy struggled with a theological perspective that spoke authentically to their beliefs. “The idea of ‘black theology’ emerged when a small group of radical black clergy began to reinterpret the meaning of the Christian faith from the standpoint of the black struggle for liberation in the United States during the second half of the 1960s. To theologize from within the black experience rather than be confined to duplicating the theology of Europe or white North America was the main objective of the new black theology.”[i] This theology would give voice to the voiceless and speak “of God’s liberating presence in a society where blacks were being economically exploited and politically marginalized because of their skin color.”[ii] While many voices were heard during the formative years of this new emerging theology, one would crystalize and become the voice crying in the wilderness. James Cone would emerge not only to articulate a theology of liberation but to serve as a midwife to help birth and nurture an American theology that spoke of a God who was on the side of exploited and oppressed Blacks.

There was a gap in American theology, and Cone filled that gap with a God who dared to put on skin and become flesh for the world. It is now time for humanity to follow the one who became human so that we can truly be all that we were created to be, the authentic expression of the Creator—love.

Emerging as the academic voice of Black theology, Cone published his first radical book in 1969, “Black Theology and Black Power.” This work blended the seeming divergent views between Black power and the civil rights movement. It was the beginning of Cone’s work that would speak of a God on the side of the oppressed. But Cone’s position was not just that God is on the side of the oppressed but that God in Christ is the liberator of both the oppressed and the oppressor.

Black theology is a liberation theology that helps the helpless see a Christ who is not foreign. It expresses the very essence of God. In this theological perspective, God’s love is manifested for all, not some. It is radical in that not only is God on the side of the oppressed, but God in Christ is also a reconciling God. Cone may have seemed aggressive in how he portrayed white America; however, his was a very candid view. It was an attempt to hold up a mirror so that America could truly see herself. Here was a theology that empowered the oppressed to stand up and the oppressor to change. Both acts would involve risk and work. The risk would be viewing the love of God from God’s eyes. Mainline Christianity in America suggests that God shows no partiality, yet it presents a gospel that speaks for some and not all. Black theology views the God of the biblical text as one who cared enough to put on flesh and, moreover, to step into the struggle of the wretched among us, sit with those who have been rejected, walk with those who have been dismissed, and eat with those who are deemed unworthy.

The God of scripture does not simply side with the victim at the exclusion of the victimizer. Such a God would be one who takes sides. Cone presented a theology that revealed God on the side of the oppressed, not at the marginalization of white America. Any theology that presents the Divine as taking a side presents an idol and not a munificent Creator who cares. Cone’s work teaches us about a God who dared to become human to show us how to live. I see James Cone as “the voice of one crying out in the wilderness, ‘Make straight the way of the Lord’” (John 1:23). He was the John the Baptist of this modern era, baptizing with the waters of liberation while preaching, “Repent, repent!”

While reading Dr. Cone’s work is challenging, it is a candid narrative of American history that reveals the sobering reality that we must shift our view of the Divine to truly be more inclusive. It is this view that the gospel presents, of a God who loved the world so much that he gave his only Son to save those who will believe on him (John 3:16). This is the foundation of God’s love for humanity as a whole: “God so loved the world . . .” I see Black theology as the voice that embraces a God who loves the world. Such a view is radical because it pushes not only whites but everyone out of complacency to see one another as God sees us. There was a gap in American theology, and Cone filled that gap with a God who dared to put on skin and become flesh for the world. It is now time for humanity to follow the one who became human so that we can truly be all that we were created to be, the authentic expression of the Creator—love.

Rev. Dr. Greg Johnson is pastor of Cornerstone Community Church, Endicott, New York.

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.