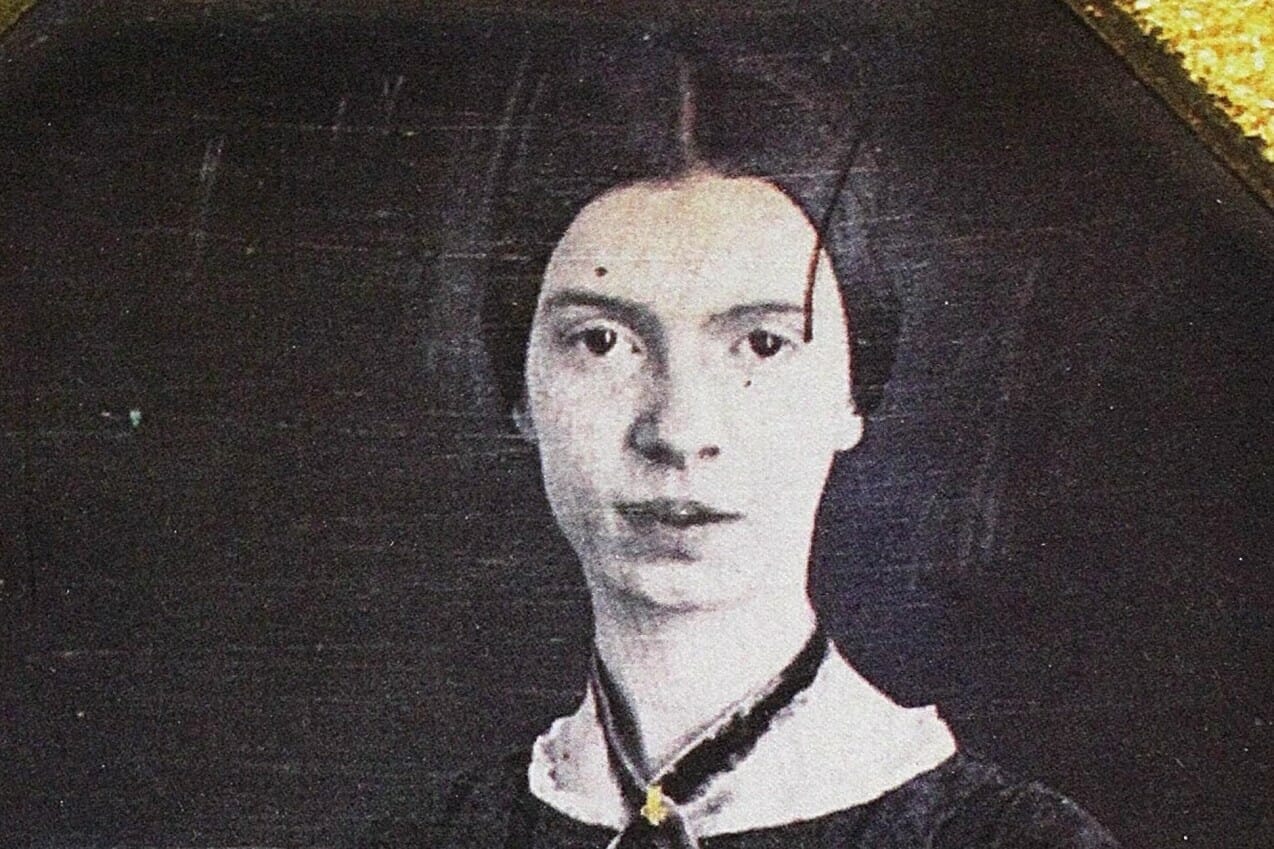

Photo by Wendy Maeda/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Emily Dickinson: Spiritual-but-not-religious ahead of her time

When I visited the Emily Dickinson Museum in Amherst, Massachusetts, I was fascinated to learn about her spirituality and her relationship to her church. Dickinson was brought up going to church and participating in the religious life of her community in Amherst, attending services with her family at the village meetinghouse, Amherst’s First Congregational Church. Congregationalism was the predominant denomination of early New England, and Dickinson’s family was deeply engaged in the local white-steepled congregational church.

The Museum’s website explains that “Ministers from the church were regular guests at the Dickinsons’ house, and several became close friends. Emily commented on sermons in her letters: ‘We had such a splendid sermon from that Prof Park – I never heard anything like it . . .’ (L142)…Like most Amherst families, the Dickinsons held daily religious observances in their home. Dickinson received her own Bible from her father at age 13. Her familiarity with the Bible and her facile references to it in letters and poems have long impressed scholars.”

The Museum continues to relate how Emily Dickinson stopped going to church: “In Dickinson’s teen years, a wave of religious revivals moved through New England. One by one, her friends and family members made the public profession of belief in Christ that was necessary to become a full member of the church. Although she agonized over her relationship to God, Dickinson ultimately did not join the church – not out of defiance but in order to remain true to herself: ‘I feel that the world holds a predominant place in my affections. I do not feel that I could give up all for Christ, were I called to die.’ (L13).” Lutheran pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer, in his book “The Cost of Discipleship,” wrote “When Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die.” That idea may have been a bit too heavy for a young teen to embrace. In time, Dickinson stopped attending services altogether. She wrote in Poem 236:

“Some keep the Sabbath going to Church

I keep it, staying at Home

With a Bobolink for a Chorister

And an Orchard, for a Dome.

“Some keep the Sabbath in Surplice

I, just wear my Wings

And instead of tolling the Bell, for Church,

Our little Sexton – sings.

“God preaches, a noted Clergyman

And the sermon is never long,

So instead of getting to Heaven,

at last I’m going, all along.”

The Museum further notes that “Although Dickinson’s immediate family accepted the poet’s decision to keep the Sabbath ‘staying at home,’ her father once asked Rev. Jonathan Jenkins, minister of the First Congregational Church from 1867-77, to meet with his daughter to assess her spiritual health. Rev. Jenkins’s diagnosis? ‘Sound.’”

She was sound spiritually, assessed her pastor, but not religious. Emily was spiritual-but-not-religious ahead of her time. Today the term “spiritual but not religious” is so common that it is recognized by its acronym SBNR. The Atlantic reported in 2018 that one in five Americans consider themselves spiritual but not religious—20% of our nation’s population! The religious landscape is changing as fast as the climate. The SBNRs – who tend to be more educated, younger, and liberal, according to the Barna research organization – recognize some form of the Divine or something larger than themselves, but reject organized religion. Like Emily Dickinson, they may be sound spiritually, but the church is not meeting their needs. When a SBNR person does attend a worship service, often on Christmas, Easter, or another holiday, they can feel out of place. Sometimes they feel criticized for their lack of external religious practices, which reminds them of the very reason why they don’t want to be there in the first place.

We in the church are well-served to take every precaution not to alienate the SBNR. When we encounter them, let there be no criticism, no judgment, no condemnation, no making them feel like prodigal children, not treating them as outsiders, no imposing our theology or spirituality upon theirs, and never any moral feelings of superiority to assume their spirituality is less valued or cherished than ours. Because… we could find ourselves on the wrong side of God’s spiritual fence. The key word is empathy. Let us struggle to feel with those who identify, like Emily Dickinson, as spiritual-but-not-religious.

Those of us who have tried to give our all to Christ and to Christ’s church face a conundrum as to how we should encounter our brothers and sisters (and our children and grandchildren) who are spiritual but not religious. Let us be like the parents of Emily Dickinson, who affirmed her, embraced her, and welcomed her at the table.

Jesus did. His entire life pointed, not to himself, but to the Divine. He was not an organization man. His own institutional religion rejected him at every turn. WHAT? You would think that his organized religion would have embraced him, lifted him up, proclaimed him a hero, and hung upon his every word. Nope. Just the opposite. When he went to speak in his hometown synagogue, they ran him out of town, and came close to driving him off a cliff. It was quite clear that he was not welcomed there. “When they heard this, all in the synagogue were filled with rage. They got up, drove him out of the town, and led him to the brow of the hill on which their town was built, so that they might hurl him off the cliff.” (Luke 4:28-29).

It was not organized religion that ignited Jesus’ creative spark. He connected with people in common life – the marketplace, by the side of the road, in people’s homes, on a hillside, in a boat, out in the fields, and just about every place where people gather except for in organized religion. When Jesus wanted to feel particularly close to God or when he had something extra special to share with those closest to him, he went up to the mountain. We read very little about Jesus and his disciples being church people (or synagogue people). It actually seems that Jesus was a champion of the spiritual-but-not-religious, and perhaps today that might be how he would identify himself – especially if he witnessed how organized religion, in many places, has become deeply politicized around hot-button issues instead of around the basic principles which formed the basis of his spirituality. We have no reason from the Bible to believe that Jesus’ disciples, who carried on his work in starting the church, were anything but spiritual-but-not-religious.

Those of us who have tried to give our all to Christ and to Christ’s church face a conundrum as to how we should encounter our brothers and sisters (and our children and grandchildren) who are spiritual but not religious. Let us be like the parents of Emily Dickinson, who affirmed her, embraced her, and welcomed her at the table. We are dealing with twenty percent of our population, so we cannot ignore them. We acknowledge that our beloved community, our church, does not meet their needs, and that, God forbid, we may be a reason why they reject religion. The Divine has nothing to fear from those who seek to encounter the Divine in ways or practices different from our own. We, in the church, have nothing to lose from extending an extravagant welcome and inclusion of those who desire to know God in ways different from our own. An arms-outstretched warm hospitality is more God-like than an arms-folded litmus test to pass in order to be included.

Emily Dickinson never returned to her family’s religious roots. Many SBNR will never return either, and that is not our objective. Our best hope, for this and for future generations, is to model the extravagant welcome of God, the loving and compassionate parent, and to recreate a church where every variety of spirituality is as welcome as you and I are, by God’s grace. “Come to me, all…” (Matthew 11:28). All. May God grant that we may be found spiritually sound.

The Rev. John Zehring has served United Church of Christ congregations for 22 years as a pastor in Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Maine. He is the author of more than 30 books and e-books. His most recent book from Judson Press is “Get Your Church Ready to Grow: A Guide to Building Attendance and Participation.”

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.