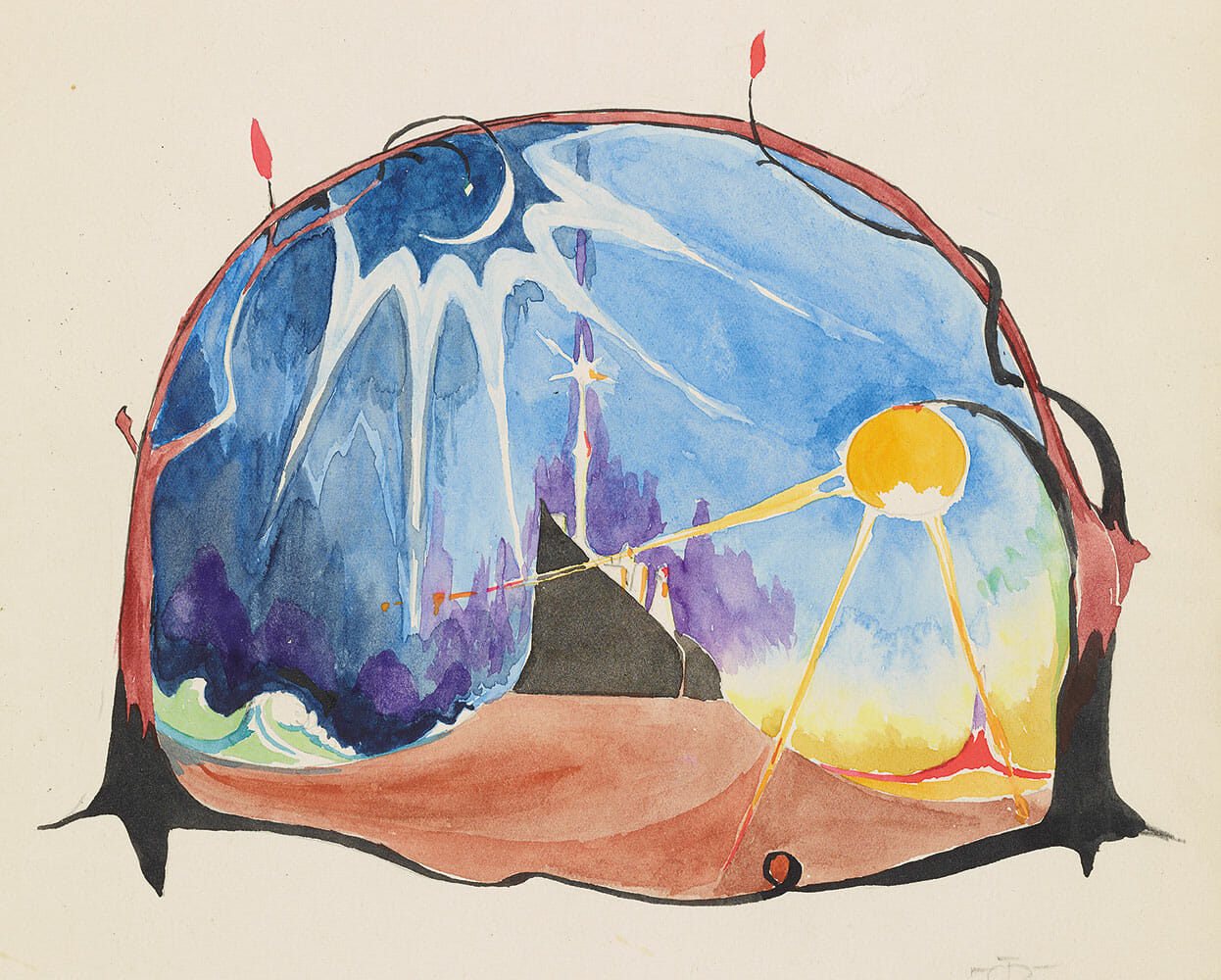

J. R. R. Tolkien (1892–1973), The Shores of Faery, 10 May 1915, watercolor, black ink, pencil. Tolkien Trust, MS. Tolkien Drawings 87, fol. 22r. © The Tolkien Trust 1995.

Ending a catastrophe—proclaiming and providing glimpses of what J.R.R. Tolkien called eucatastrophic joy

Rev. Jerrod H. Hugenot

May 20, 2020

For generations now, J.R.R. Tolkien holds a particular reverence among his devotees. For example, first on his “Colbert Report” (Comedy Central) and then later “The Late Show” (CBS), Stephen Colbert demonstrates on occasion (and gleefully) his high nerd level knowledge of the books. Then there is Leonard Nimoy singing “The Ballad of Bilbo Baggins,” but haven’t we suffered enough lately?

Admittedly, I have been slow to read “the source material,” instead better acquainted with Tolkien by way of Peter Jackson’s six films adapting “The Hobbit” and “The Lord of the Rings” trilogy. Among the books I am reading is “The Tolkien Reader,” a collection of shorter pieces by Tolkien (New York, NY: Ballantine Books, 1966). It includes the essay “On Fairy Stories,” presented by Tolkien originally in the late 1930s and later published widely in the 1960s. The essay explores the concept of the “fairy story” in literature, and Tolkien brings his scholarly weight to the exploration, making a denser read for those more acquainted with his noted “Hobbit” book.

In the midst of this lecture-turned-essay, Tolkien refrains from the line of reasoning that “fairy stories” are left only in the realm of children’s literature. Children may have the most immediate grasp of the power of the stories, yet Tolkien discourages readers from discarding such tales as we move into adulthood. Instead, he encourages the reader to consider carefully the story as an engagement of fantasy, recovery, escape, and consolation, concepts that can seem untethered to reality, yet may indeed turn us back to a more clear-headed engagement of the world around us, if engaged properly.

In the essay’s latter pages, Tolkien coins a new word, Eucatastrophe, to communicate “the consolation of fairy stories, the joy of the happy ending: or more correctly of the good catastrophe, the sudden joyous ‘turn’ (for there is no true end to any fairy-tale)” (Tolkien Reader, p. 85-6).

In the epilogue to the essay (p. 87ff), Tolkien explicitly grounds his critique within a Christian worldview. Eucatastrophe blends the “joy” or intense thanksgiving in the midst of a time of great peril, and the denouement serves up a twist that regains what was feared lost.

Further, Tolkien marvels, “It is the mark of a good fairy-story, of the higher or more complete kind, that however wild its events, however fantastic or terrible the adventures, it can give to child or man that hears it, when the ‘turn’ comes, a catch of the breath, a beat and lifting of the heart, near to (or indeed accompanied by) tears, as keen as that given by any form of literary art, and having a peculiar quality.” (p. 86)

I know many are struggling and will struggle. I admit many were struggling mightily with socioeconomic injustice well before any sign of a global pandemic was on our national horizon. But I do hold out the hope and the trust that God is with us even now, providing a pathway toward the ending that benefits all creation.

In the late 1930s, as Tolkien gave this lecture, England was in the midst of great peril from the growing Nazi threat. The lecture saw formal publication in 1947, after the Second World War and as England began its difficult post-war era recovery. It makes his comment above about the “turn” that much more earned, seeing Europe and the rest of the world plunged into WWII, and still an observation he could put into a published essay. After the tumult, Eucatastrophe was abundant, even if not everything was tidily resolved and the full horrors of the era remain slowly acknowledged. For example, the Holocaust remains a lingering wound in the global village, unhealed as its lessons go unheeded with subsequent violence and hate in subsequent generations, even today.

Tolkien admits eucatastrophe “does not deny the existence of dyscatastrophe, of sorrow and failure; the possibility of these is necessary to the joy of deliverance; it denies (in the face of much evidence, if you will) universal final defeat and in so far is evangelium, giving a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief” (p. 86).

In speaking grandly, Tolkien remains tethered still to the world as we know it. The good news, the Great Joy, is stronger than sorrow and loss. Tolkien connects this observation to his Christian belief, a Story steeped in life and death as well as the resurrection of Jesus Christ. The ideologies and idols of the world will try to lay claim to that as well, yet do they offer a sense that in the grim and desultory, especially there, a greater Good shall have the last word?

In the midst of daily press briefings here in New York where we hear sadly of hundreds of COVID-19 patients who died each day (at the time of this writing), I also see the scenes around the nation as groups plan “gridlock” events in other state capitols, trying to force the ending of “stay at home” orders. Much tumult is on display between local, state, and federal officials, certainly driven by the already heightened political atmosphere. I know the fear of neighbors, communities and yes, congregations, who wonder what impact, short and long-term, this will have.

I know many are struggling and will struggle. I admit many were struggling mightily with socioeconomic injustice well before any sign of a global pandemic was on our national horizon. But I do hold out the hope and the trust that God is with us even now, providing a pathway toward the ending that benefits all creation.

And that end shall be good, whatever catastrophe bears down on us. We have a story that calls us to proclaim and provide glimpses of eucatastrophic joy.

Yet there is hope to be found with the first responders, medical personnel, and those who are keeping essential businesses going. The civic leaders who set aside their partisan impulses also are a sign of hope, even if they seem a rarer species these days. And certainly, I see fellow clergy, particularly in the chaplaincy field, providing the highest fidelity to their vocation to care and to serve right now.

The Rev. Jerrod H. Hugenot is associate executive minister, American Baptist Churches of New York State.

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.