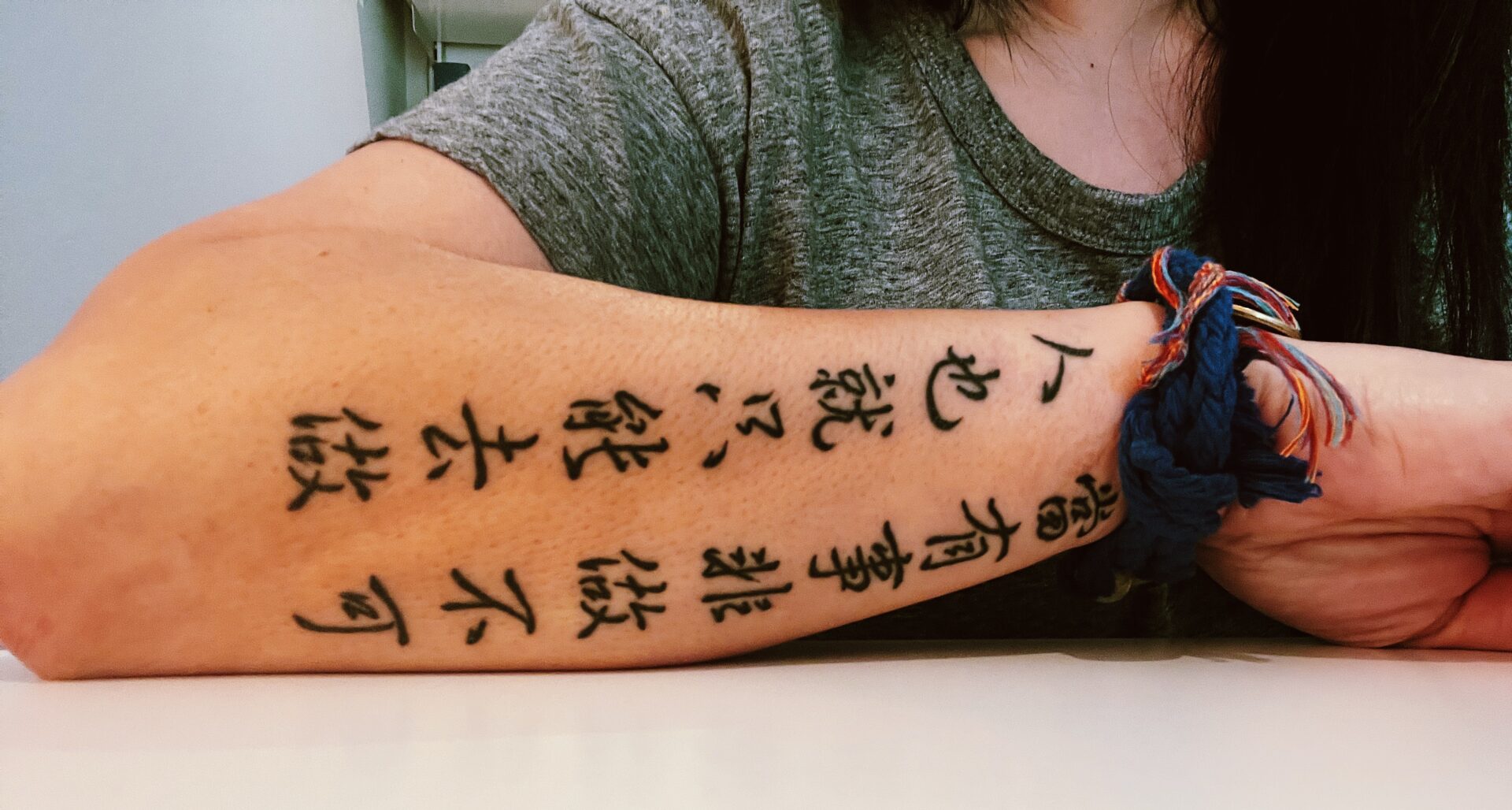

Photograph by Lauren L. Ng

It’s in our bones

I’ve got some new ink. This tattoo, like my others, has a story.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 remains the only law in American history to deny naturalization in or entry into the United States based on a specific ethnicity or country of birth. This law was in place when the 1906 San Francisco earthquake caused a huge fire that destroyed public birth documents which led to the proliferation of “paper sons and daughters”— Chinese immigrants who saw an opportunity to work around the racist Chinese Exclusion Act by coming into possession of birth documents not their own. The Chinese Exclusion Act was finally repealed in 1943, but anti-Chinese sentiment and distrust remained high. It was just four years after this Act was repealed, in the spring of 1947, that my paternal grandmother and uncle arrived on the western shores of the United States on the USAT Admiral W. S. Benson, to join my grandfather after he was honorably discharged from the U.S. Army for his service during World War II.

For several months, my three family members participated in hearings (interrogations, really) by the United States Department of Justice as the Immigration and Naturalization Service attempted to confirm their identities and familial relation to one another before allowing my grandmother and uncle to reside permanently as citizens. I have in my possession 107 pages of the typed transcripts from these hearings that my father obtained from the National Archives many years ago. In these transcripts one sees how my grandfather, grandmother, and uncle were lined up shoulder to shoulder before the interrogation officers, examined like livestock. An officer states that the boy’s eyes look like the alleged father’s but there is no facial resemblance to the alleged mother. In another section one hears my grandfather and grandmother being questioned separately about how many paces there were between the front door and the barn door of their village home back in Taishan (the assumption being that if they answered differently, this would be evidence of them misrepresenting themselves).

Page 31 of the transcript details word for word a portion of an interrogation of my grandmother by an immigration officer in which he asks her if her mother’s feet had been bound or unbound. My grandmother explains that they were at one point bound, and then later were unbound.

The interrogator asks, “Did your mother have any difficulty walking”

“Yes, she had some difficulty,” replies my grandmother.

The interrogator persists, “How could your mother have worked on the farmland, raising sweet potatoes and other vegetables, if her feet had been unbound?”[i]

And my grandmother answers, “When one must do something, one just has to do it.”

I had her words, first spoken in Cantonese, then translated into English during the hearing and in the transcript, retranslated into Chinese characters (hànzì) by a friend. My Ngin Ngin’s words are a testament to the strength of immigrants, familial bonds, and the stories of our ancestors that we carry with us every day. This strength is memorialized as ink on my arm, but what if I told you I also carry my grandmother’s strength, her grit, and her fortitude in my very bones?

This concept is already becoming well researched and documented. Books like My Grandmother’s Hands by therapist and trauma specialist Resmaa Menakem examine the damage racism wreaks upon our bodies, our actual physiology, our blood, and our nervous system. Menakem writes, “The body, not the thinking brain, is where we experience most of our pain, pleasure, and joy, and where we process most of what happens to us. It is also where we do most of our healing, including our emotional and psychological healing. And it is where we experience resilience and a sense of flow.”[ii] Related to Menakem’s work, just a couple of weeks ago, at the first session of “Love the Lord With All Your Mind” — a three-part series offered by ABHMS’ Asian Ministries and the Center for Continuous Learning, guest speaker Dr. Jessica ChenFeng spoke about the ways human migration influences diet, which then affects physical health and overall wellness. Speaking from an Asian American perspective, Dr. ChenFeng reminded me that even though I was born here in Phoenixville, Penn., my physiology is more wired to thrive on the native foods of my motherland China than it is the foods that grow naturally on this continent. We carry history in our bodies. There’s stuff going on in our very bones.

If our bones are alive, if they carry in them the strength of our ancestors, trauma of humanity’s transgressions, even predispositions for nutrition… if they — like the Scriptures say — have the capacity to be troubled, to ask questions, to experience restoration, to be reanimated as recipients of God’s ruah (breath), then we have to wonder, what is in our bones?

Modern science tells us that despite bones being associated with death, they are a locus of life in our bodies. Our bones are alive with cells, blood vessels, nerves, and pain receptors. They can grow, repair themselves, and even change their shape. They protect the body’s vital organs, help to maintain precise levels of needed minerals, and produce the blood in our bone marrow. What modern science reveals to us about bones being exceedingly alive, the Scriptures affirm:

“O Lord, heal me, for my bones are troubled.” (Psalm 6:2 NKJV)

“All my bones shall say, “Lord, who is like You?” (Psalm 35:10)

“Pleasant words are as a honeycomb, sweet to the soul, and health to the bones.” (Proverbs 16:24 KJV)

“He said to me, ‘Son of man, can these bones live?’ And I answered, ‘O Lord God, You know.’ Again, He said to me, ‘Prophesy over these bones and say to them, ‘O dry bones, hear the word of the Lord.’” (Ezekiel 37:3-4 NKJV)

If our bones are alive, if they carry in them the strength of our ancestors, trauma of humanity’s transgressions, even predispositions for nutrition… if they — like the Scriptures say — have the capacity to be troubled, to ask questions, to experience restoration, to be reanimated as recipients of God’s ruah (breath), then we have to wonder, what is in our bones?

That’s a journey for each of us take personally… to learn our family’s history, to examine what resides in our bones so we can tend to what needs tending, heal what requires healing, and preserve what ought to be preserved.

But this is also a journey we are taking at American Baptist Home Mission Societies. This mission organization is a body unto itself, with bones that carry the history of almost 200 years. Our institutional bones carry the imprint of commissioning 50 missionaries to share the Good News across the eastern and central United States in 1832. They carry the imprint of responding to the “Alabama Resolutions” of 1844 with the adamant message that no, we would not be party to any arrangement that would imply the approbation of slavery (in this case, commissioning a missionary that owned slaves). Our bones carry the imprint of having founded 27 institutions of higher education for Freed People after the Civil War, of sending an envoy to Washington to work for treaties favorable to Indigenous peoples, of ministering to Japanese Americans in internment camps during WWII, and of leading the way among Christians in work with disaster response, refugee resettlement, children in poverty, and other profound social justice issues that shape our nation each and every day. And because of the work and witness of our generation, our institutional bones now carry the imprint of addressing the mental health crisis in our families, churches, and communities, of advocating for and celebrating our LGBTQIA+ siblings, of contending for the differently abled among us, of dismantling the claims of white Christian nationalism, of standing with the people of Palestine.

Just as I carry the strength of my grandmother, we all carry the strengths, the joy and the grief, the risk-taking and the “failed” experiments, the bold steps and the missteps, the disappointments and hopes of almost 200 years of American Baptist home mission in our very bones. We would do well to memorialize this physiological legacy — if not with ink on our skin, then with a posture of faithfulness to which we come to work each day. God’s mission through us is in our bones. May these bones be a locus of life today and in the days to come.

Rev. Dr. Lauren L. Ng is director of the Leadership and Empowerment Team at American Baptist Home Mission Societies. Her Doctor of Ministry research was on AAPI women in ministry.

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.

[i] Unbound feet were extremely painful in their own right, due to the expansion of broken bones and crushed appendages that made it extremely difficult to walk.

[ii] Menakem, Resmaa. My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending our Hearts and Bodies. Las Vegas: Central Recovery Press, 2017, p. 12.