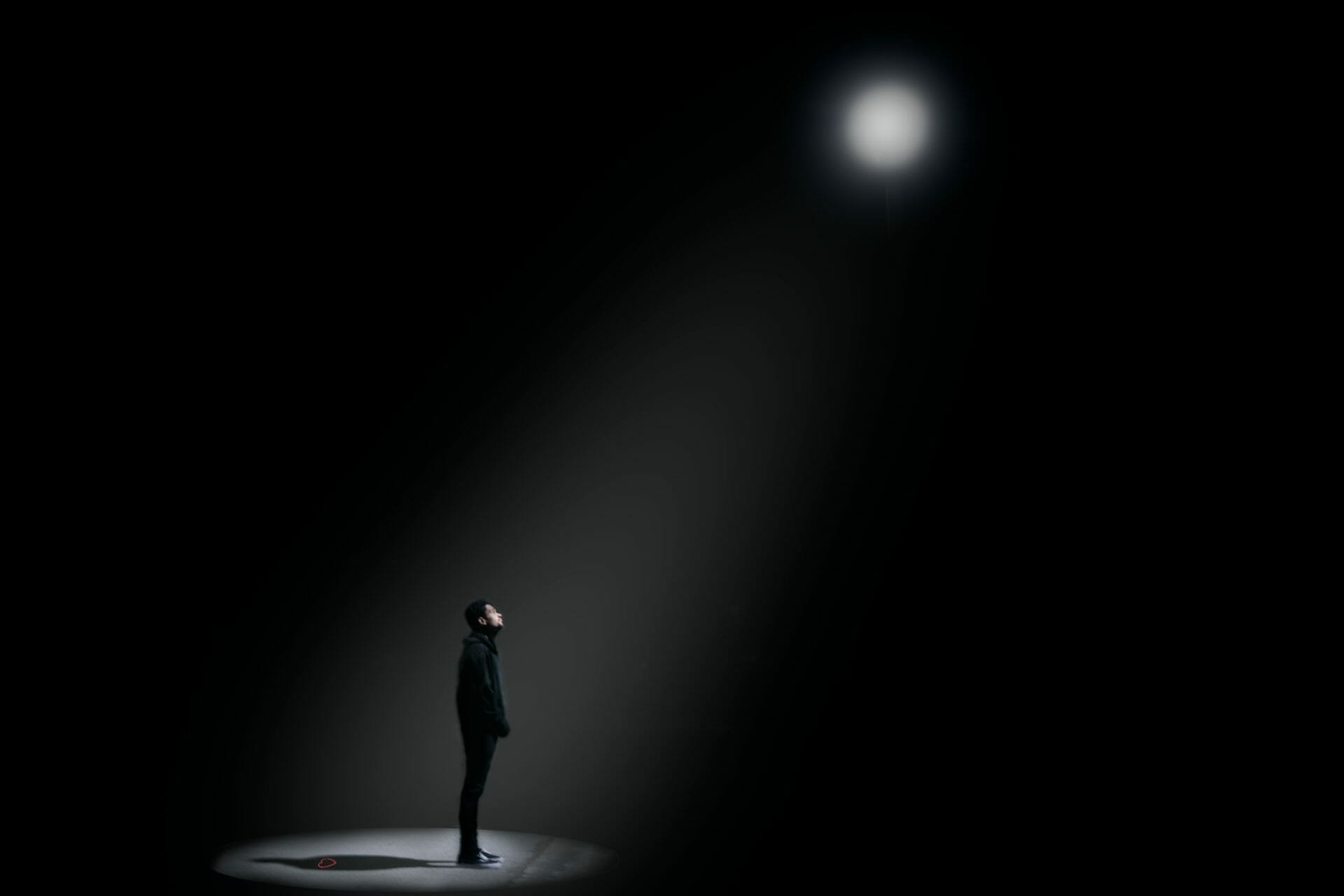

Photo by Matthew Menendez on Unsplash

Microscope, spotlight, learning curve, stakes—When leadership anxiety gets to be too much

You might know the conventional wisdom that a host shouldn’t try a new recipe when having guests over for dinner. You might have had a nightmare where you were about to take an exam for which you hadn’t studied or performed in a play for which you hadn’t rehearsed. If you’ve tried for a souffle and had it flop when your boss was coming over, or actually gotten up on stage having just barely mastered your lines, you understand better what it’s like to be a leader during a pandemic.

There was no dress rehearsal or drill for what leaders have had to manage over the past nearly two years. Pastors and lay leaders in congregations, for instance, have had to learn new technology not just on-the-fly, but with an audience of people they’ve promised to serve.

What can we do to reduce the burnout that’s driving leaders back into bubbles, unable to bear the stress of performing their duties without the comfort that comes with knowledge, experience, and expertise? Empathy. And empathy requires some sense of how the other feels. So, what happens to a person when they’re operating on previously unexplored terrain?

Different parts of the human brain take care of different functions. On scans, scientists can see that new tasks light up one area of our minds’ electrical functioning. Routines light up a different area. Fight, flight, or freeze activates another still. To perform a familiar task in a way that’s wildly unfamiliar makes for hard and disorienting brain work. For experienced and competent people, who’ve invested much of their identities in being experienced and competent, the shift can be scary. We can’t make the excuse to our communities, “This part of my brain is inexperienced and terrified right now.”

Many years ago, I went through a search process with an educational institution that was seeking a new leader. I was excited about the job’s possibilities, but ultimately I pulled out before a final decision on my candidacy took place. The school had been through a lot of trauma and both internal and external constituents were watching the search like hawks. Seeking to protect themselves from a bad hire, the search committee worked me over and talked to more than a dozen references. I understood their anxiety, and I also knew that the job would have been a big change for me, drawing me into areas where I had little experience and would need time and grace as I learned.

There was no dress rehearsal or drill for what leaders have had to manage over the past nearly two years. Pastors and lay leaders in congregations have had to learn new technology not just on-the-fly, but with an audience of people they’ve promised to serve. Furthermore, we as a society have been so desperate for Covid-19 to be brief, to be over, that we have failed to adjust our expectations of leaders.

In my email indicating I no longer wanted to be considered, I wrote that the combination of the microscope under which I’d find myself, the spotlight that would be cast on me, the learning curve I’d be climbing, and the stakes for the institution were I to make big mistakes, seemed too risky. Since then, I have used this egregiously mixed metaphor in other settings to describe when leadership anxiety gets to be too much.

Microscope: leaders need to be monitored, but when their every move is judged and scrutinized, they become self-conscious and less confident. Skittish leaders do not inspire trust from others, so the microscope leads to a vicious cycle of compounding self-doubt. I had a colleague who started his first ministerial call during a hot summer. Several congregants and his senior colleague critiqued how often he sipped his water during his first sermon. He didn’t last a year.

Spotlight: the healthier the institution, the less obsessed it is by its executive leader. The reverse is, of course, also true. Stakeholders need to distribute their loyalty between the institution’s mission, history, community, and leaders at least somewhat evenly. Those that put leaders on pedestals cause their leaders to feel unbearably responsible when times are tough, and times are tough a lot lately.

Learning curve: change leadership is complicated and difficult. In order to be effective in carrying out change, leaders need time to get to know the context, learn an institution’s history, and build trust. They also have to be willing and able to change themselves. When we are learning and changing, we make mistakes. Our communities need to give us space to get up and get back in the race after we trip. Amidst Covid-19, the learning curve is steeper for everyone. Why, therefore, are we harder on our leaders when they make mistakes? Because we want our leaders to make us feel safe, it’s difficult to accept that this is their first pandemic, too.

Stakes: I have served as a leader both in institutions under existential threat and whose futures were not at obvious risk. The jobs felt completely different. Leading when the stakes are so high that the institution might not survive can be exhausting in ways that those serving sustainable institutions cannot imagine. Those who work in higher education know that some students come with a built-in cushion: if they find themselves falling, a net will catch them. Others have no cushion — financial, familial, or otherwise — and they are the ones most likely to fall apart when tensions rise. Institutions are the same way in that communities with no margin for error exhaust leaders.

Microscope. Spotlight. Learning Curve. Stakes. The pandemic has intensified all four of these misfit metaphors. Under such duress, leaders’ brains are rerouting, and the parts of their brains stress has activated just aren’t as smart as the parts that got them their current jobs. Furthermore, we as a society have been so desperate for Covid-19 to be brief, to be over, that we have failed to adjust our expectations of leaders. Laboring under unrealistic expectations is that which causes DSM-diagnosable burnout.

Because I write and think about and conduct leadership day in, and day out, I’m tempted to say, “Here’s the answer to how we can make our work more manageable under these circumstances.” But, as much as I fear disappointing you, readers, this is my first pandemic, too.

Rev. Dr. Sarah B. Drummond is founding dean of Andover Newton Seminary at Yale Divinity School and teaches and writes on the topic of ministerial leadership.

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.