Photo by JD Doyle on Unsplash

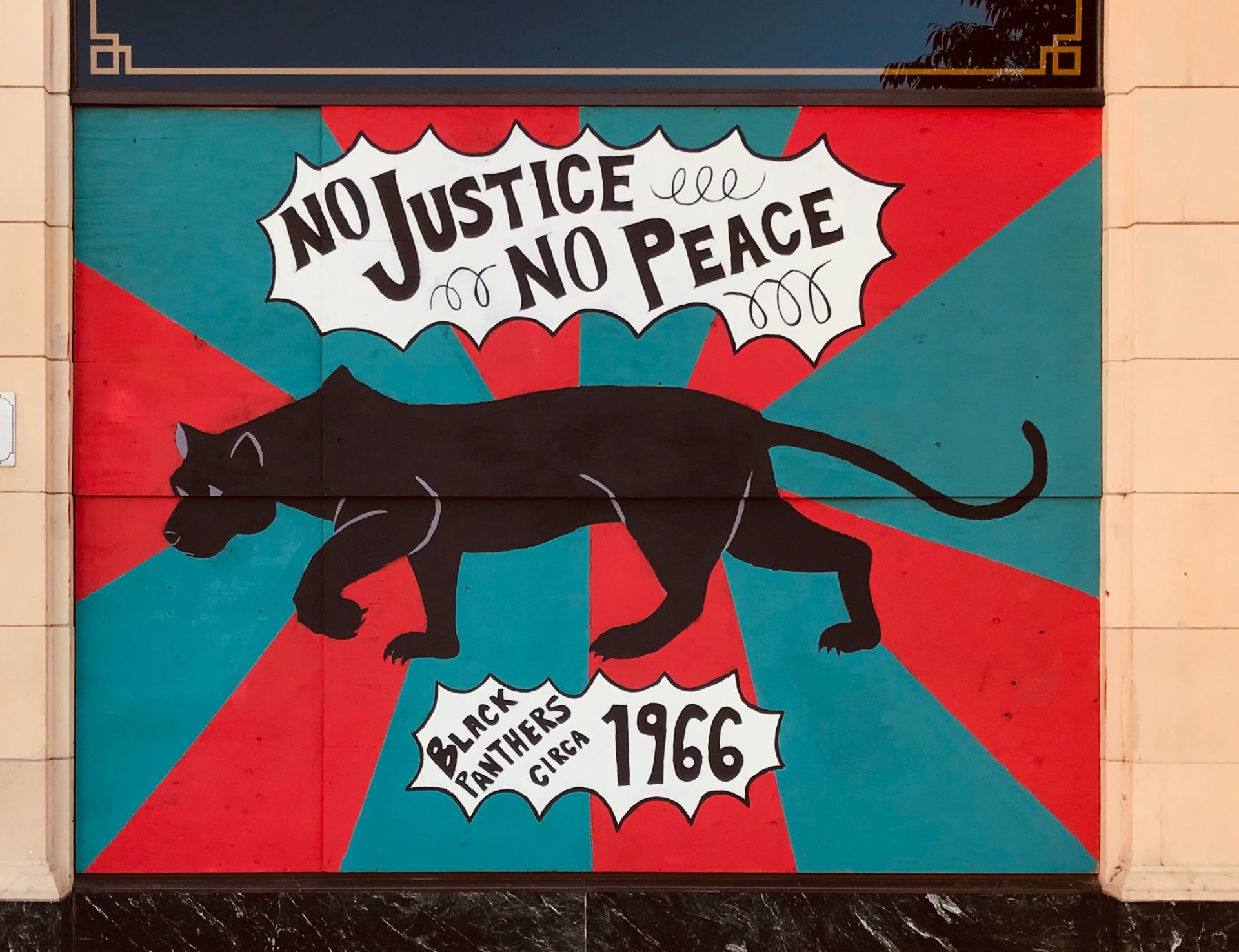

Preserving Black Panther party history is a spiritual concern

If you take a look at the list of historical places that the Society is working to preserve, then you’re sure to notice that many of them are churches. Churches were the sites of some of the party’s meetings and played a prominent role in hosting the movement’s signature free breakfast program for schoolchildren. For me, a white pastor in a suburb bordering Chicago, preserving Black Panther Party sites is not only preserving Black history; it is also preserving a time when some churches answered the call that came from outside of their church doors and engaged with the real work that needs to be done in communities.

One important site is The Armitage Methodist Church in Chicago. In 1969, The Young Lords, who worked with the party and adapted its platform, launched what they called a “church offensive” that demanded churches act on their values by serving the poor, the oppressed, and the downtrodden. This culminated in the takeover of Armitage, the renaming of it to The People’s Church, and the establishment of a daycare, free breakfast program, and health clinic within the church. Not everyone was happy about that takeover, but eventually many came to realize that The Young Lords were doing the work of the church. For instance, District Superintendent Carl G. Mettling, a denominational official in the district where Armitage resides, wrote after the takeover: “The Church has an unavoidable responsibility to the youth of Chicago on which it dare not turn its back, a responsibility to give not only the cup of cold water in Christ’s name, but to aid in the search and struggle for a more humane society for all.”

Would that the church might have such a transformation. Churches are often myopic, looking internally for the resources for reform, when often our institutions ought to train their ears on voices from outside of our communities that hold us to account. The Black Panther Party and Young Lords show that calls from outside the church can pose challenges that tangibly move faith communities towards justice, even if later than thought.

In my community, Evanston, IL, which passed a first-in-the-nation reparations initiative in 2019 and has distributed its first payments to Black residents who faced racism in housing, education, healthcare, employment, and a host of other categories, white communities of faith are finally beginning to reckon with The Black Manifesto. Delivered by The Black Panther Party’s minister of foreign affairs and director of political education, James Forman, in 1969 at Riverside Church in New York City, the manifesto called specifically for reparations from American churches and synagogues. While it demanded $500 million, it only raised about $22,000. Now, in Evanston, those same communities are beginning to question how their resources and very existences are bound up with white supremacy. It is never too late to do the right thing.

In Chicago, the preservation of the Black Panther Party’s historical sites is more than just a question over whether a place should be on a national register – it’s a spiritual question. The places that are central to the Black Panther Party also have the capacity to move us still today to consider their urgent, burning questions. And isn’t that the work of the church?

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.