Radical resister, Malcolm X: The man, minister, Mecca

Rev. Dr. Greg Johnson

February 21, 2020

When an individual departs this life, what is said about them after they are gone, many times gives a vivid portrait of them. Things are said of an individual after they have departed this world, that many would dare not say during their waking moments. As Martin Luther King, Jr. famously said, “The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.”[i] During Malcolm X’s life as a resister of American racism, he was described in various ways, and many were not positive or flattering. Still, the message, the man, and the work are an integral part of African American history.

When you look at the life of Malcolm X, you will readily notice that he did not shy away from challenges or controversy. He did not necessarily seek them out, but they were the byproduct of the work that he was involved in. This speaks volumes of Malcolm’s character and his passion.

When you look at the life of Malcolm X, you will readily notice that he did not shy away from challenges or controversy. He did not necessarily seek them out, but they were the byproduct of the work that he was involved in. This speaks volumes of Malcolm’s character and his passion.

Malcolm did not simply evolve into a mesmerizing public figure. He was the product of the black church. Malcolm was born to Rev. Earl and Louise Little. His father, a Baptist minister, was an integral part of the Garvey Movement in the late 1920s. “The year Malcolm was born Marcus Garvey, a pan-Africanist and advocate of black independence…, had been jailed by the U.S. government.”[ii] Malcolm’s early childhood did not shield him from the struggles that his parents endured as activists. His father was found struck down by a trolley car in Lansing, Michigan in 1931. Louise Little struggled to care for her family after the death of her husband, Rev. Earl Little. Under the stress of being the target of violent acts because of her political activism and caring for her children after the loss of Earl’s income, Louise had a breakdown and was institutionalized in early 1939. The children went to live with relatives. Malcolm was an extraordinary individual at a young age. He graduated from junior high with all A’s and was voted class president. He shared that in junior high he informed his teacher that he wanted to be a lawyer. He was in an integrated school; however, he was one of very few blacks in his school. His teacher informed him that he needed to “be realistic about being a nigger.”[iii] These were Malcolm’s formative years, and as for most of us, our formative years have a profound impact on who we become. For Malcolm, his formative years would build the foundation and the fervor of becoming an activist, advocating black self-pride and independence.

A survey of Malcolm’s life reveals pivotal moments that led to the man that he eventually became. While there were notable experiences, each pivotal moment resulted in an action he took that pointed him in a specific, life-altering direction. Dropping out of school at 15 was the first sign of Malcolm’s revolt against America’s racist attitude. African Americans found it difficult to find employment even with a high school diploma—without one, the odds of unemployment were higher. Malcolm found employment doing menial jobs in Harlem and Boston. He became a street hustler, going by the name of “Detroit Red.”[iv] Malcolm was arrested and “In February 1946…sentenced to ten years in prison.”[v] Michael Eric Dyson noted that “Malcolm’s self-reinvention was greatly enabled by his conversion to Islam.”[vi] In the 1950s Black Muslims “proselytized vigorously among black inmates in America’s prisons.”[vii] Malcolm credit Elijah Muhammad for his transformation. He was released from prison in 1952, as a Muslim with the name Malcolm X. Prison offered Malcolm the opportunity for intense study of his newfound religion and offered him the opportunity to become a student of American Christianity.

As a minister of the Nation of Islam, Malcolm was the mouthpiece of Elijah Muhammad. He would become the figure for the Nation of Islam. It was in Harlem, New York, at Temple Number 7, where Malcolm rose to national prominence as the spokesperson for the Nation of Islam and Elijah Muhammad. He preached black pride and self-love and articulated the feelings of black America. Malcolm said, unapologetically, what black America feared to say due to retribution from whites. Those who heard him speak, heard what Cornel West described as “black rage”[viii]. However, his rhetoric was not chaotic, uninformed or lacking intellect. Malcolm was concise with his words, he was intentional about what he said, and directed his discourse not only to white America but to blacks as well. He demonstrated passion for his people, he echoed his concern for the disparity that was being experienced and did not shy away from dialogue where race was the subject. As a minister of the Nation of Islam, while Malcolm was the speaker, he made sure that his message was approved by Elijah Muhammad. This time in his life allowed him to become a proficient orator and catalyst for radical resistance. Malcolm painted all whites with the same brush stroke, evil. It is conceivable to see how his life experience informed his malcontent for whites.

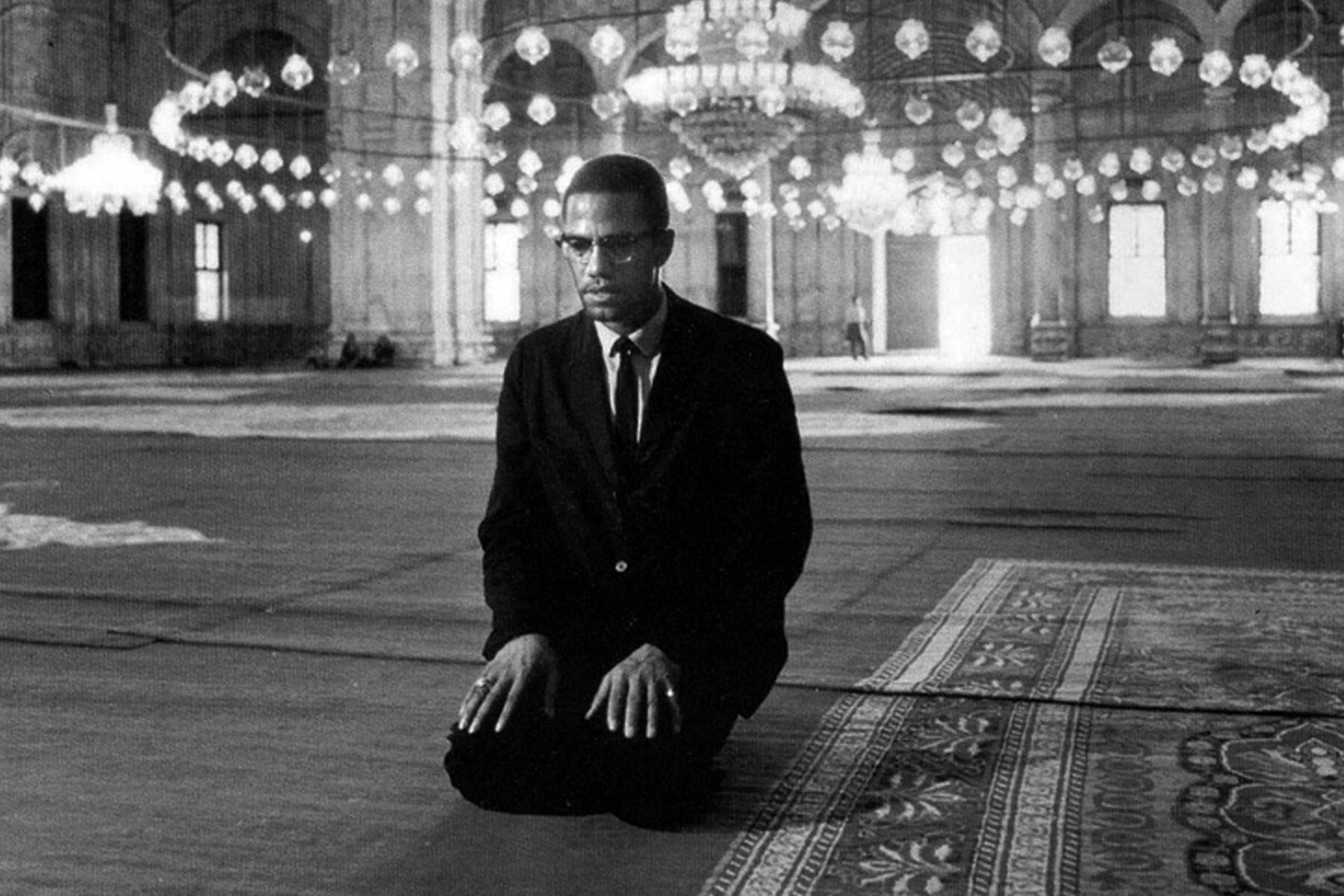

One of the most fascinating things about Malcolm was his ability to evolve. While he continued his position of radical resistance, his posture towards individuals who were not black did shift. Malcolm’s second conversion experience came from his trip to Mecca in 1964. It was this experience that shifted his racial sensitivity and perspective. He experienced brothers of lighter complexion and white Arabs treating him with equity. He experienced an acceptance and embrace from those who were different from him. This experience Dyson termed as a conversion experience and transformative. This experience enabled Malcolm to speak to other African Americans that desired change but were not as radical as he was. While he said what many were feeling, he understood that there were other approaches to gaining the same goal. It was after his Mecca experience that he was open to dialogue and truly listening to the philosophy of Martin Luther King Jr.’s non-violence.[ix] It is truly unfortunate that America did not get to experience the full measure of this stage of his life. Malcolm’s life demonstrates that we may be a product of our circumstance, however, it is possible to grow through our experience to become more self-actualized.

The Rev. Dr. Greg Johnson is pastor of Cornerstone Community Church, Endicott, N.Y.

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.

[i] Martin Luther King Jr., Strength to Love, (Fortress Press, Philadelphia, PA, 1963, 1981), 35.

[ii] Henry Hampton, Steve Fayer, Voices of Freedom: An Oral History of the Civil Rights Movement from the 1950s Through the 1980s, (Bantam Books, New York, NY, 1990), 242.

[iii] Ibid. 242.

[iv] Ibid. 242.

[v] Ibid. 242.

[vi] Michael Eric Dyson, OPEN MIKE, (Basic Civitas Books, New York, NY 2003), 344.

[vii] Henry Hampton, Steve Fayer, Voices of Freedom: An Oral History of the Civil Rights Movement from the 1950s Through the 1980s, (Bantam Books, New York, NY, 1990), 243.

[viii] Cornel West, Keeping Faith, (Routledge Classics, 2009), 135.

[ix] Michael Eric Dyson, OPEN MIKE, (Basic Civitas Books, New York, NY 2003), 345.