Shepherd your ‘little church’ as a thermostat to alter society

Aidsand F. Wright-Riggins

January 20, 2020

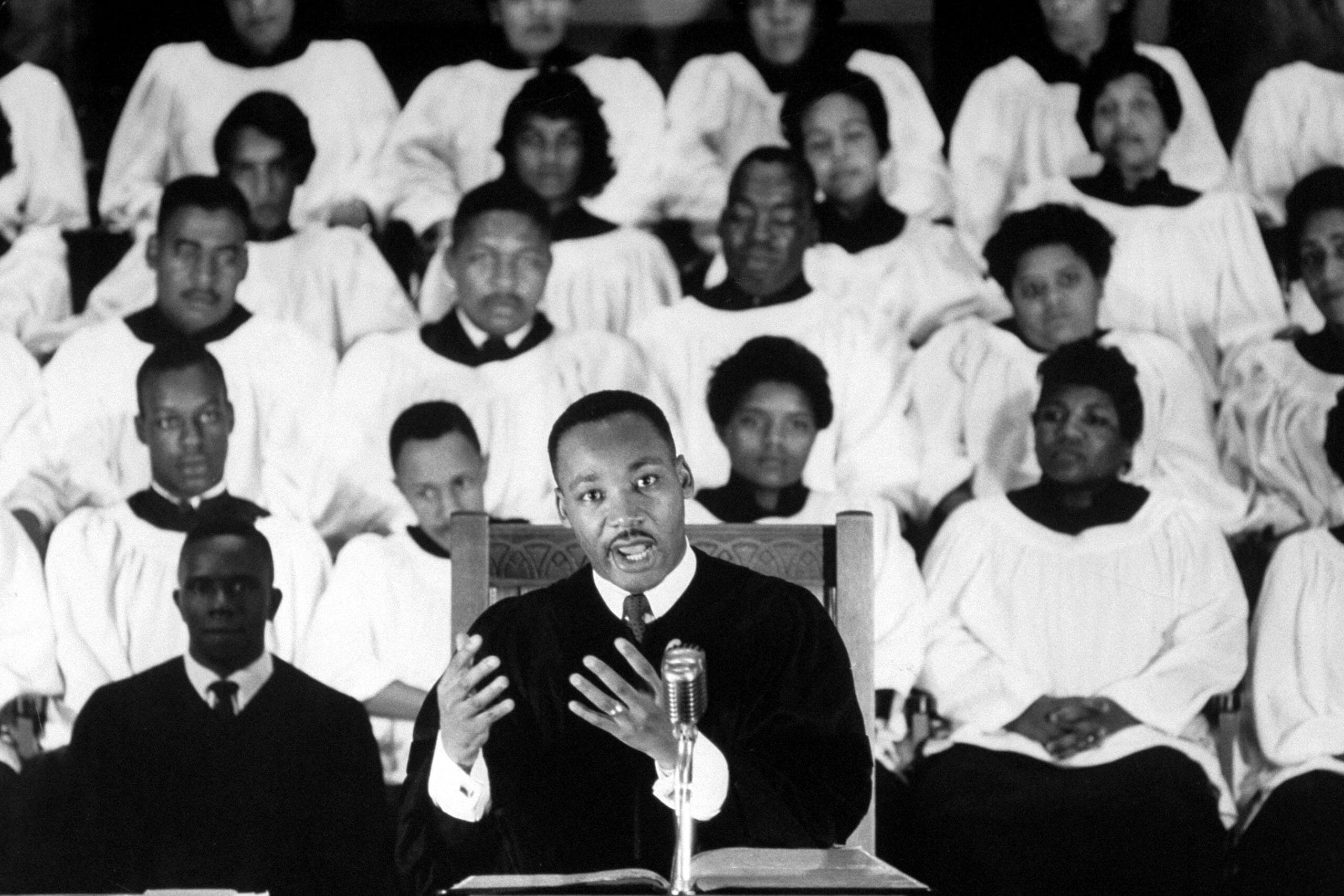

On Martin Luther King Jr. Day 2020, I would love to hear parents in their homes and speakers in auditoriums focus on King’s April 16, 1963, “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.”

There are gems galore in that letter. Reading it, I am most drawn to the inseparability of faith in the fight for social justice.

King addresses this theme when he says, “[T]he early Christians rejoiced at being deemed worthy to suffer for what they believed. In those days, the church was not merely a thermometer that recorded the ideas and principles of popular opinion; it was a thermostat that transformed the mores of society.”

He continued, “But the Christians pressed on, in the conviction that they were ‘a colony of heaven,’ called to obey God rather than man. Small in number, they were big in commitment. They were too God-intoxicated to be ‘astronomically intimidated.’”

I have long been convinced that experientially, the first church is the little church and that little church is one’s immediate or extended family.

On King Day, I celebrate that my parents and my first church home saw themselves as a “colony of heaven.”

They planted within me and my community of birth a spirit that refused to be intimidated by any notion of marginalization or inferiority.

My parents caught the vision of becoming a demonstration plot for the kingdom of God despite their impossible beginnings.

My mom grew up the daughter of dirt farmers and garbage collectors in Muskogee, Oklahoma.

By faith, her impoverished parents chose this middle female child of seven children to become the first and representative child of theirs to go off to college.

Mama became an educator and dramatist who excelled in telling stories and writing poetry to entertain and empower young people to stand up, stand out and stand for something other than simply themselves.

She never took her blessings for granted or thought she had somehow pulled herself up by her own bootstraps. She believed the blessed are obliged to bless others.

Daddy escaped from a sharecropping plantation in Irish Ridge, Texas, when he was 18 years old by “liberating” the sharecropper’s truck and then stealing away his parents and siblings to Houston in the dead of the night.

Except for my mom and my dad’s siblings, I do not recall anyone ever calling him anything other than “Mr. Riggins or Deacon Riggins.”

He kept a book filled with pictures on our living room table that was always out on display. Two pictures caught my attention.

One picture was of a black person being lynched and set on fire. The other was of a group of black men marching and holding signs reading “I am A Man.”

Daddy was a cook and artist by trade, but I am convinced that that book was my father’s daily sermon to his little church.

The local congregation I grew up in was one where religion and a commitment to fighting for racial justice went hand in hand. That church was more often a thermostat than a thermometer.

It taught us that the racialization of Ham and his cursing was a damn lie; that Moses was a liberator and not simply a lawgiver and, “If the Son therefore shall make you free, ye shall be free indeed” (John 8:36).

I regularly heard sermons preached that were subversive and challenged the status quo.

My church raised money to support King and the freedom movement down south.

It charted a bus to take many of our members in Los Angeles to the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in August 1963. Relatively small in number, we were big in commitment.

Today, I pray for a grand emergence of a new generation of radically Christian and socially subversive parents who will shepherd their little church faithfully and unabashedly.

Today, I pray for a grand emergence of a new generation of radically Christian and socially subversive parents who will shepherd their little church faithfully and unabashedly.

Today, as we celebrate King and the freedom movement of which he was an exemplar, I encourage congregations – red, yellow, black, white and brown – to be thermostats rather than thermometers.

Toward the end of the Letter from a Birmingham Jail, King penned words that relate as much to the third decade of the 21st century as they did to the church of 1963.

I pray that little churches of families and local congregations will reflect on them during this season:

“The judgment of God is upon the church as never before. If today’s church does not recapture the sacrificial spirit of the early church, it will lose its authenticity, forfeit the loyalty of millions and be dismissed as an irrelevant social club with no meaning for the twentieth century. Every day, I meet young people whose disappointment with the church has turned into outright disgust.”

However small in number we may be, let us be big on commitment in 2020 and beyond.

Aidsand F. Wright-Riggins is Mayor of Collegeville, Pennsylvania, Co-Executive Director of the New Baptist Covenant, and Executive Director Emeritus of the American Baptist Home Mission Societies. Used by permission of EthicsDaily.com.

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.