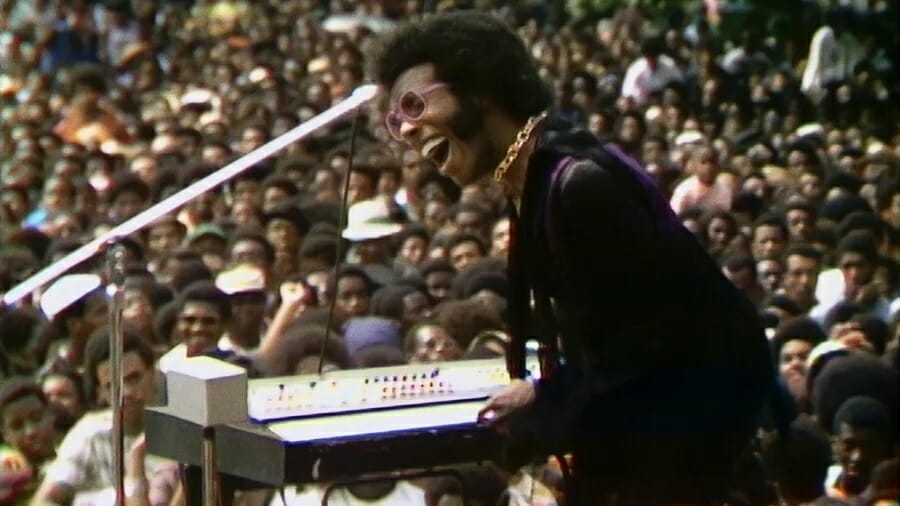

Sly Stone performs at the Harlem Cultural Festival in 1969, in a still from the film Summer of Soul.

Photograph courtesy of Mass Distraction Media.

Soulfully revisiting the past

In the summer of 1969, the Mt. Morris (now Marcus Garvey) Park in Harlem, New York City, was the site of the Harlem Cultural Festival. Over six weekends, the park was filled with concerts featuring some of the era’s most popular African American musicians, performing to large capacity crowds. The festival was called “the Black Woodstock,” referring to the other large concert event during that summer.

Woodstock looms large in the cultural memory of many Americans. Its imagery of hippies dancing euphorically in the muddy fields to Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin engrains their youthful bliss in our memories thanks to the footage often played in retrospectives about the 1960s on television over the past decades.

However, the footage from “Black Woodstock” largely remained forgotten in its film canisters, until a recent documentary directed by Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson of The Roots. Questlove assembled the footage into the remarkable documentary “Summer of Soul,” released in theaters in mid-2021 and streaming on Hulu.

This film reframes the cultural legacy of 1969 by presenting the performances to a new generation. Many reviewers have noted the Harlem Cultural Festival’s footage was deemed at the time as not marketable to a national audience. The racism then, and now, make this film’s release even more important today. It serves as a time capsule of musicians in their heyday (or on the ascendance to later greatness) yet mired in the struggles for racial equality and the daily existence of being a person of color in America. It’s a festival and a call to ground oneself in the ongoing tumult.

For a documentary, the film lets many moments go by without a lot of voiceover commentary or shortcut edits, instead letting the viewer feel caught up in the moment of a performance and the energy of the crowd. The great singer Mavis Staples was part of the festival lineup, performing with her family as the Staples Singers. She remembers the unique moment in time the Harlem Cultural Festival created for those performing as well. Staples recalls, “When you talk about music, this Black festival [was] some of every kind, some of every style. Jazz, blues, gospel, all of it [was] good.”

Woodstock looms large in the cultural memory of many Americans. However, the footage from the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival (also known as “Black Woodstock”) largely remained forgotten in its film canisters until a recent documentary, “Summer of Soul,” directed by Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson of The Roots.

Indeed, the range of performances you will enjoy in this musical is remarkable. In interviews, Questlove spoke of living with this footage for weeks, listening and watching it continuously to determine the performances to highlight and how to frame the narrative of the documentary’s exploration of the events within the Festival and greater society. Early in the film, a young Stevie Wonder dazzles with his turn at the drum set, a surprise for younger viewers more accustomed to Wonder singing at the keyboard. The film ends with Nina Simone’s powerful performance and her call to the crowd to rise up against the forces that held them back. Woodstock had its social influences, yet the Harlem Cultural Festival drove home all the issues at stake for its key audience.

In an interview with Variety, Questlove observes the Festival came at a time when

“the dividing line [developed] between a generation that thought of themselves as ‘colored’ or ‘Negro’ and a generation that thought themselves as ‘Black;’ a generation that was used to only men in suits, giving a well-subdued polite performance, as opposed to a generation, a younger generation seeing a group dress up in their street clothes, intersectional and intermixed like Sly and the Family Stone. That seemed totally foreign to them at the time…A difference between kind of Martin Luther King civil rights movement and the Black Panther civil rights movement, so a lot was happening in 1969. And, the evidence is there for you to see…”

One moment involves the Rev. Jesse Jackson, just over a year since he witnessed firsthand the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in Memphis. He recounts that somber experience and what unfinished work was still ahead, and then Mavis Staples and Mahalia Jackson share the microphone in an impromptu rendition of “Precious Lord, Take My Hand,” a favorite hymn of Dr. King. The elder and younger singers certainly are hailed as divas of their respective generations, however, the sacred moment they created together in that moment will linger with viewers long after the film ends.

The film dips into the news of that time, as the concert’s schedule coincides with the first Moon landing. Local reporters visit the Festival seeking comment, and the responses from attendees range from an initial polite response to the socioeconomic critique not being covered by mainstream media at the time, demanding to know why the money was spent on lunar expeditions with so much poverty and need. Watching “Summer of Soul” in July 2021 felt eerily resonant as Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson competed for the bragging rights as the first private company to launch the first “commercial travel” space flight. After his (brief) trip to space, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos thanked his employees and customers for making this trip possible, an irony considering Amazon’s corporate practices and success at corporate tax evasion while so many this past year have struggled mightily in the pandemic and with other long-running socioeconomic woes still unchecked.

The “Summer of Soul” documentary arrives in the middle of a global pandemic, vitriolic political struggle, and a resurgence in efforts to enact voter suppression laws. The youth of Woodstock and the Harlem Cultural Festival aspired to great ideas for society. When this long-neglected footage of the Harlem Cultural Festival returned, it still found America in search of its soul.

The Rev. Jerrod H. Hugenot is associate executive minister, American Baptist Churches of New York State.

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.