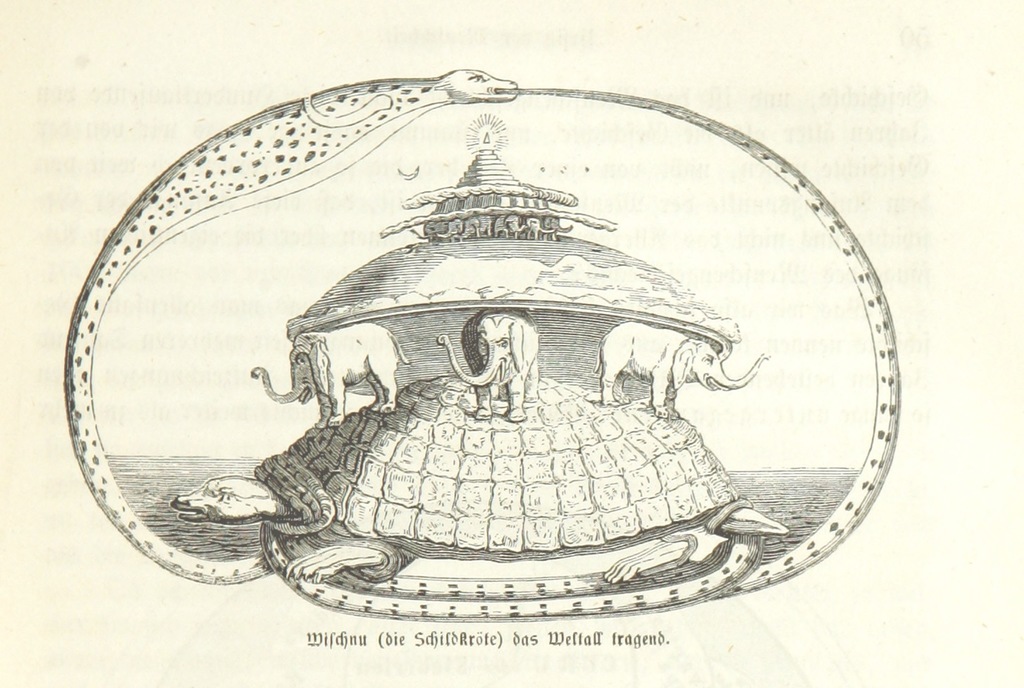

Image of Discworld from “Der Mensch, die Räthsel und Wunder seiner Natur. … Vierte Auflage” vol. 1.

British Library via Flickr/Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

There is no Jew or Greek, slave or free, ‘cause we’re all coppers: The Discworld Night Watch as a metaphor for church community

April 11, 2024

[Warning: This article contains mild spoilers for Terry Pratchett’s Discworld books. If you don’t wish to be spoiled, go immediately to your local library and read all 41 books. The article will wait. It’s worth it.]

During the worst days of the pandemic, I was desperate for something fun to read. A friend recommended Terry Pratchett’s “Discworld” series. I had enjoyed the show “Good Omens” based on the novel of the same name which Pratchett wrote with his dear friend, Neil Gaiman, and so I thought I’d give “Discworld” a chance. Pratchett was a confoundingly prolific writer, writing 41 books set in “Discworld” from 1983 until his death in 2015. He recommended starting the series with book 3, since he felt it was there he had figured out what he was doing. Trusting the author, that’s what I did.

The stories of Discworld take place on a flat planet, 10,000 miles in diameter, balanced on the back of four elephants, standing on a giant turtle flying through space. The stories parody classic mythology, folklore, and fantasy elements and use them to make satirical points about issues which plague us in the round world. One doesn’t need to start the series anywhere in particular. The internet is full of debates on the “best way to read the Discworld books.” Though I read the stories in publication order, Pratchett writes each book so that it is accessible to a first-time reader, and my wife read the books in their individual series.

Some books follow the adventures of a coven of witches, led by the indomitable Granny Weatherwax. Some follow the work of the Death of Discworld, who only ever speaks in small caps in the text, so it is clear when he is speaking to those who are near or post death. (I confess that if the Death of Discworld does not walk with me as I cross over to the other side, I will enter glory a little disappointed). Some books follow how the inventions of the printing press, moving pictures, or the steam engine affected the people on the disc. The books that hooked my wife, however, were the stories of Sam Vimes of the Night Watch — the police force of the city of Ankh-Morpork.

When we first encounter Sam Vimes, he is a cynical, alcoholic cop, passed out in the gutter mourning the death of a friend and colleague. The police force was little more than a joke. That is, until Carrot Ironfoundersson arrived. Carrot was a human who had been adopted and raised by dwarfs (his dwarf name translates to “head banger”). When Carrot joins the collection of misfits in the Night Watch, his dwarfish upbringing compels him to follow the letter of the law. His simple, but sincere, passion for doing what is right reawakens in Sam Vimes the desire to do right as well. The Night Watch is revitalized and instead of just four misfit coppers, the Watch is suddenly hiring new recruits and stationing them all over the city.

At first, the new recruits came mainly from the city’s human population, until the interest group, “The Campaign for Equal Heights,” insisted the Watch should hire more dwarf members of the watch for better representation. This led to the hiring of troll members of the watch (trolls are made of stone, and therefore, adversaries of the frequently mining dwarfs). Across the series of “Watch Books,” the Night Watch becomes more diverse and inclusive. The Watch hires a werewolf, a zombie, golems, a vampire, a gnome, an Igor, various gargoyles, and even an accountant.

Jesus understood the value of a good parable to make a point understandable. In reading the Discworld books, I am certain Terry Pratchett did, too.

Vimes had a philosophy, “All coppers are just coppers.” But he also had his own prejudices. Beyond his own struggles, he recognized the additional challenge of having a werewolf and vampire patrol together or a troll and dwarf walking down the street as a team. Just because they were “all coppers” doesn’t mean all the old prejudices were gone. At times, Vimes leaned into the diversity and mixed the composition of patrols so that the city could see different species working together in an effort to calm inter-species violence. Vimes (and the reader) discover that although he pushed against the “diversity, equity, and inclusion” program that led to this diverse group of cops, the individual gifts each species brought to the watch led to crimes getting solved and the world being made better. The Night Watch became everyone’s.

In that way, the Night Watch becomes a remarkable parable for the church. Much like Sam Vimes, the church in Acts was dragged to more diversity, equity, and inclusion in its early years. In Acts 2, what started as a group of Palestinian Jews on the morning of Pentecost became a group of Jews of various ethnic backgrounds by the evening. That diversity soon became a challenge when it came to light that some widows weren’t being treated fairly because of their ethnicity in Acts 6. Once that issue was addressed, soon after in Acts 8, the church had to send an inspection team to confirm that Samaritans could receive the Holy Spirit. Then later that same chapter, individuals who couldn’t convert to Judaism before becoming Christians were welcomed — like the eunuch from Ethiopia. Ultimately, even Gentiles were offered full welcome into the church without first becoming Jewish — after a lengthy debate at the council in Jerusalem in Acts 15.

Sam Vimes recognized it might be simpler if all the coppers were human, but the Watch wouldn’t work as well if they were. While it might be simpler if everyone in the church had the same gifts, Paul spent 1 Cor 12-14 emphasizing to the Corinthian church that the diversity of the body of Christ made it alive. In fact, a diverse and inclusive church is the ultimate goal. In Revelation 7, the faithful standing in front of the throne of grace are from every tribe and every nation — so many of them that no one could count them all — shoulder to shoulder. No one was above anyone else, but all were under Christ.

When Paul said that in Christ there was “no Jew or Greek, slave or free, male or female,” in Galatians 3, he was not suggesting that individuals lose their individual gifts or identities. Paul was emphasizing that no group could exercise power over any other. Our individuality still exists, but Jewish Christians could not force Gentile Christians to be Jewish. Neither could men dominate women. The punishments of the fall had been overcome by new life in Christ.

All those identities now rested under the headship of Christ. In the same way, Sam Vimes’ belief that “all coppers are coppers” meant their identities were used in the enforcement of “the law,” not the enforcement of any individual person’s or species’ privilege.

Jesus understood the value of a good parable to make a point understandable. In reading the Discworld books, I am certain Terry Pratchett did, too.

Rev. Dr. Robert Wallace is senior pastor, McLean Baptist Church, McLean, Virginia.

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.