Civil rights march on Washington, D.C., August 28, 1963.

Photo by Unseen Histories on Unsplash

Turning the world upside down: religious freedom, civil rights, and the struggle for a more just, equitable world

Several years ago, my wife did some genealogical research on her family of origin and mine. She discovered I am a distant relative of John Crandall who was born in 1618 in Westerleigh, England, and later emigrated to America. The first documentation of his presence in America is in 1643 when he appears as a grand jury member in Newport in what would become the state of Rhode Island. He became a prominent member of the First Baptist Church of Newport.

The presence of a prominent Baptist in my family tree was something of a surprise to me as I grew up in the Congregational church in Connecticut. My hometown was small, roughly 5,500 people, about an hour northeast of New York City. Easton Congregational Church was and is what you might imagine a typical New England church to be—set on a hill, small but with a tall steeple, with white clapboard siding and green shutters. Inside, the carpet was red, and the pews were white.

Baptist and Congregational churches are locally governed. While they associate with other congregations in regional, state, and national conferences or associations, no one beyond the local church has the authority to tell individual congregations what to do.

Congregationalists have two sacraments—the Lord’s supper and baptism. Baptists practice the same though we regard the Lord’s Supper and baptism as ordinances of the church, not sacraments, and Baptists do not baptize infants as Congregationalists do. Baptists practice believer’s baptism, also known as regenerate baptism or adult baptism, following a public profession of faith.

While these differences seem slight today, they were anything but during John Crandall’s lifetime. In fact, Baptists were persecuted in New England and elsewhere for their beliefs and the formation of what would become Rhode Island was a direct result of this persecution. Roger Williams, a Puritan radical who arrived in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630, was banished five years later for his refusal to practice his faith consistent with the teachings and observances of the Puritanism of the day and for his belief in the strict separation of church and state.

Williams lived for a time among the Narraganset Indians before founding the city of Providence as a haven for religious dissenters. Williams also organized the First Baptist Church in America in the city of Providence which recently celebrated 385 years of ministry.

In 1643, Williams returned to England to begin the process of securing a charter from the king a charter for the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, in which the religious liberty claimed by the colonists was guaranteed through royal decree. For the first time in history, a civil government was founded that guaranteed to its inhabitants’ absolute religious freedom.

Fast forward to 1651 when John Crandall traveled to Lynn, Massachusetts with John Clarke and Obadiah Holmes to hold religious services for the Baptists there. They were arrested on July 21, 1651, and sent to prison in Boston. Ten days later they were convicted. Clarke and Crandall were fined 5 pounds each. Holmes was fined 30. If they failed to pay the fine, the punishment they faced was to be publicly whipped.

Obadiah Holmes chose differently and because he did, he is held in higher regard today. Holmes believed that to pay the fine was to admit to the legitimacy of the sentence which he believed to be unjust. After all, he was practicing his faith according to the dictates of his conscience, something he believed all people should be free to do. So, he refused the fine and chose to be publicly whipped. His punishment was 30 lashes, one for each pound of the fine. Holmes risked his life for his faith, for his belief that his cause was just, and while he was being whipped. Writing later about the event, Holmes related “…having joyfulness in my heart, and cheerfulness in my countenance…I told the magistrates, ‘You have struck me as with roses.’”

Why would the Puritans go to such lengths to enforce the religious orthodoxy of their day? Why would the Baptists go to such lengths to oppose them? The differences may seem slight to us today. They were anything but at the time. In a world in which people are not free to practice their faith as they see fit, doing so is a direct challenge to public order. In a world in which the institutions of church and state were not separate but one, suggesting they should be separated was a dangerous notion. Clarke, Crandall, and Holmes turned the world upside down, though it took some time.

The First Amendment to the Constitution providing that Congress make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting its free exercise, would not be ratified for 140 years, in 1791. It would take nearly two decades more, in 1818, for the Congregational church in Connecticut to finally be disestablished and it wasn’t until 1843 that Jewish congregations were even allowed to incorporate in the state.

For much of the colonial period into the early years following independence the salaries of clergy of favored denominations in several states were paid from tax dollars, a practice that continued in Connecticut into the 1830’s.

It was Baptists and other religious minorities who fought these practices, who turned one world upside down and gifted us the world we live in today where I am free to practice my faith and others are free to do the same.

Which brings me to Luke’s account of the visit of Paul and Silas to Thessalonica. Luke tells us Paul was in the synagogue three sabbaths, so, a period of at least three weeks. Some Jews were being converted but far more Gentiles. But the authorities are not happy with the presence of Paul and Silas for the disorder they are causing.

Like their Baptist compatriots 1600 years later, they would soon be accused of turning the world upside down. As with the charges against Crandall, Clarke, and Holmes this indictment was not wrong. It was an accurate assessment of what they were doing. Suggesting there is another king greater than Ceasar was a threat to public order that challenged the Roman way of doing business which was to allow freedom throughout the empire for local customs and for local religious belief and practice—so long as those practices remained essentially private.

In his book, “Foolishness to the Greeks: The Gospel and Western Culture,” missiologist Lesslie Newbigin wrote, “The early church never availed itself of the protection it could have had under Roman law as a cultus privatus dedicated to the pursuit of a purely personal and spiritual salvation for its members. Such private religion flourished as vigorously in the world of the Eastern Mediterranean as it does in North America today. It was permitted by the imperial authorities for the same reason it is permitted today—it did not challenge the political order.”

Paul and Silas challenged the political order. Like Obadiah Holmes they had accomplices, in this case a man by the name of Jason who lived in Thessalonica. According to Luke, a mob was searching for Paul and Silas. When they could not find them, they attacked Jason’s house, dragging him before the authorities and effectively charging him with guilt by association.

“These people who have been turning the world upside down have come here also, and Jason has entertained them as guests,” Luke wrote. Jason provided Paul and Silas with hospitality, opening his home to them, no doubt feeding them, entertaining them, and providing them a base of operations and a place to sleep while they were in Thessalonica. According to Luke, “They are all acting contrary to the decrees of the emperor, saying that there is another king named Jesus. The people and the city officials were disturbed when they heard this, and after they had taken bail from Jason and the others, they let them go.” Like John Crandall years later, Jason was free to go so long as he paid his fine.

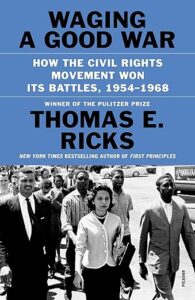

This month, The Christian Century published my review of “Waging a Good War: A Military History of the Civil Rights Movement, 1954-1968,” by Thomas Ricks. Ricks offers a novel interpretation of the Civil Rights Movement as a kind of war—a series of campaigns on carefully chosen ground that eventually led to victory. Ricks, who has written books about World War II, Korea, and Vietnam, brings his experience as a war correspond in Somalia, Bosnia, Afghanistan, and Iraq to bear on his analysis of the strategy and tactics of the Civil Rights Movement. By couching key moments in military terms, he deftly narrates the successes and setbacks that resulted in the United States becoming a genuine democracy for the first time in its history.

This month, The Christian Century published my review of “Waging a Good War: A Military History of the Civil Rights Movement, 1954-1968,” by Thomas Ricks. Ricks offers a novel interpretation of the Civil Rights Movement as a kind of war—a series of campaigns on carefully chosen ground that eventually led to victory. Ricks, who has written books about World War II, Korea, and Vietnam, brings his experience as a war correspond in Somalia, Bosnia, Afghanistan, and Iraq to bear on his analysis of the strategy and tactics of the Civil Rights Movement. By couching key moments in military terms, he deftly narrates the successes and setbacks that resulted in the United States becoming a genuine democracy for the first time in its history.

“The Siege of Montgomery. The Battle of Birmingham. The March on Washington. The frontal assault at Selma.” While this language may seem jarring at first given the movement’s association with nonviolent resistance, it clarifies the strategic thinking and organized effort at the heart of the struggle for civil rights for African Americans. The military history approach is helpful, even imperative, Ricks argues, for understanding and applying the lessons of the movement to politics today—including efforts to restore the voting gains of the 1960s.

Ricks writes, “The Civil Rights Movement was often creative, but it was rarely spontaneous. Its members did not just take to the streets to see what would happen. Rather, weeks, and even months of planning and preparation went into most of its campaigns.” While Ricks notes the significance of visible actions such as marches, speeches, and other public events, the focus of the book is on the extensive planning, strategic thinking, and reconnaissance that were fundamental to the success of civil rights campaigns.

Much of this work was done by the Jasons of the Civil Rights Movement —the hundreds, even thousands of men and women who volunteered, who opened their homes, who provided food and shelter, so that campaigns like the March on Washington could come to fruition and be successful. As significant as the speeches and public demonstrations were, none of them would have happened without the tireless and necessary work of people whose names will never be recorded in a history book, or who will be named briefly, like Jason, and thereafter forgotten. But it was the tireless and necessary work of these individuals who made it possible for Martin Luther King Jr to stand on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial and share his dream.

Such moments were not spontaneous. They were not accidental. They were meticulously planned, executed, and supported by the work of hundreds and thousands of Jasons of the Civil Rights Movement, men and women who believed all people should have the right to vote and equal access to housing, education and economic opportunity, regardless of race—who turned one world upside down and gifted us with the world we live in today where you and I are free to vote and others are free to do the same, where all have greater access to housing, education, and economy opportunity. It is not a perfect world. Problems and bias and prejudice remain, but it is a better world because of their efforts.

The question that confronted the Civil Rights Movement, that confronted Clarke, Crandall, and Holmes, that confronted Paul, Silas, and Jason, confronts is now. How will we turn the world upside down?

How will we challenge a prosperity gospel so prevalent in our culture that focuses on the financial rewards of being faithful but that seems to reward the preachers of such a gospel with riches at the expense of those who give faithfully even when it is beyond their means to do so?

How will we confront a public health crisis of loneliness and isolation resulting in record levels of substance abuse, suicide, and early death from other causes with a welcome to all that is expansive and an invitation to community that is rooted in the abundance of life Christ promised?

How will we challenge those who would bind the truth of the gospel to the power of the state, returning the church to a place of political prominence while compromising the religious liberty of others, and even of itself?

How will we challenge those who would roll back civil rights gains, who seek to restrict access to the vote and support laws limiting the ability of teachers to teach history? What will we do to defend multiracial, multiethnic democracy?

We can do these things and more in small and seemingly insignificant ways, like those of the Civil Rights Movement who opened their homes and churches to freedom riders and civil rights workers, like those early Baptists who led worship in defiance of the religious and political orthodoxy of their day, like Jason entertaining Paul and Silas as guests in his home knowing full well the jeopardy he was putting himself in by doing so.

We can do these things and more because we have faith in Christ who came so that we would have life and have it abundantly, and who invites us to extend this invitation to all.

We can do these things and more because we follow the one who promised he would be with us to the end of the age, even and perhaps especially amid a world turned upside down.

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.