Black liberation theology and Malcolm X: An unwelcomed voice

Rev. Dr. Greg Johnson

February 21, 2020

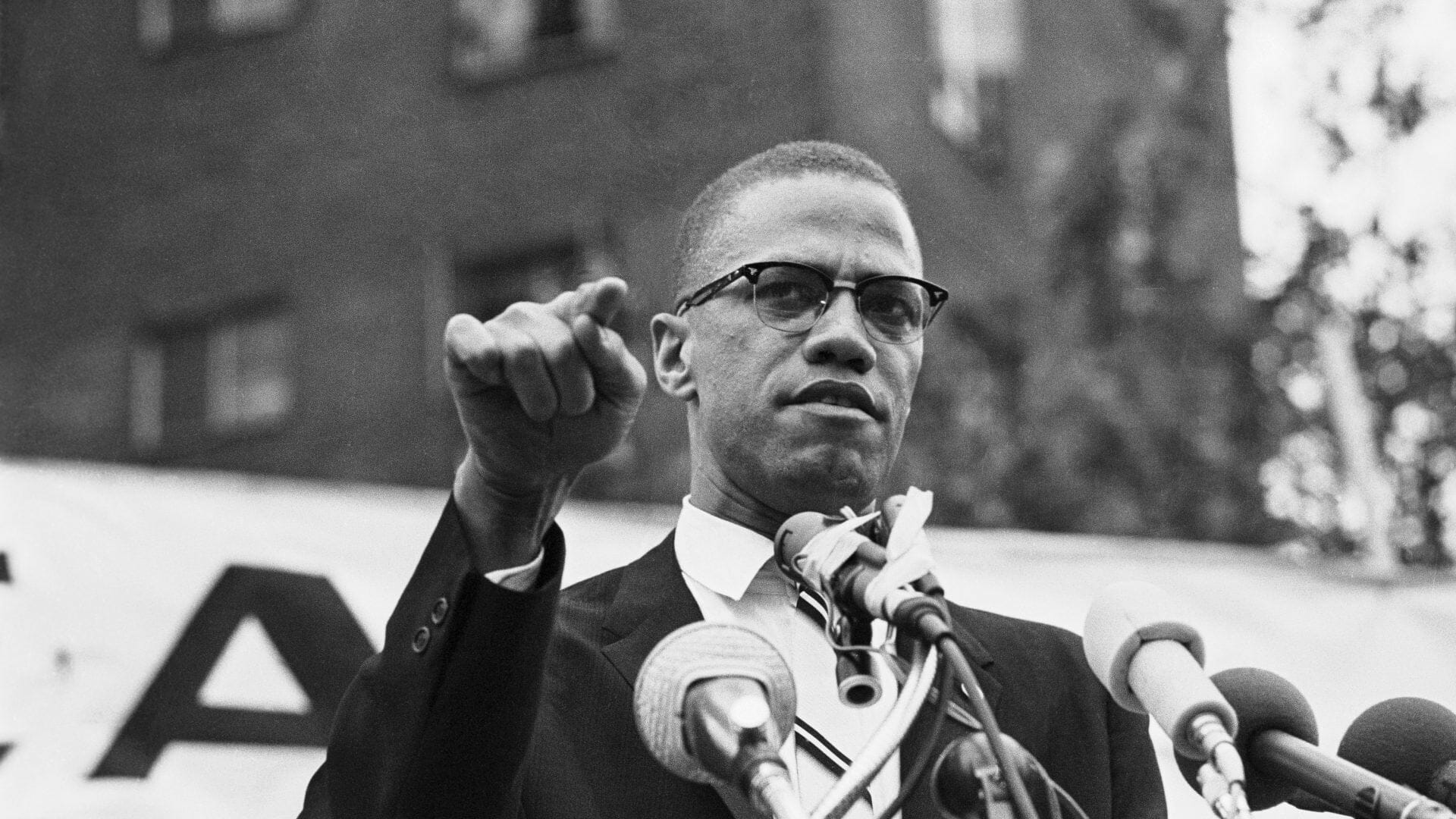

Liberation theology was birthed out of the atmosphere of struggle. Black liberation theology was birthed from the struggles of African Americans for equality. At the very core of black liberation theology is the struggle for equality, justice and truth. While American Christianity espoused the tenets of liberation in general, one voice of the twentieth century placed a mirror before American Christianity. The voice was that of Malcolm X and he was no stranger to controversy.

When figures from black history are mentioned, Malcolm may not be the most popular. However, he was undeniably the most vocal and one of the most passionate voices reflecting black liberation theology in the twentieth century. Malcolm was not a theologian in the traditional sense. However, his philosophy of black nationalism captured the minds and hearts of the oppressed of the black community.

Malcolm was a product of America’s racist practices and experienced for himself the duality that existed in American Christianity. He was born as Malcolm Little, May 19, 1925 in Omaha, Nebraska. “A dropout from school at 15, he was convicted of burglary and sent to prison in his twenty-first year.”[i] Malcolm spent six years in prison, leaving in 1952. After prison, he found his purpose and passion. As a minister of the Nation of Islam, Malcolm spoke out against the oppression of blacks in America. He not only spoke against the racist practices of America, he dealt with the racist tone and practice of American Christianity. This did not fare well with black preachers in America, let alone white preachers. Malcolm harshly criticized American Christianity, as well as the black church, for preaching a message he termed, “heaven-in-the-sky theology.”[ii]

While many black preachers at the time did not welcome Malcolm’s scathing indictment of their theology and Christian practice, his critical analysis caused many to rethink their theology and how they viewed the gospel. He intentionally insulted the image of Jesus that white Christianity used. James Cone indicated that Malcolm’s tutelage, his Christian background and his passionate studies made his “the most formidable race critique of Euro-American Christianity in the modern world.”[iii] This critical analysis created tension in the black community and the black church. Middle class black Americans, while Christians, resonated with Malcolm’s message. This made it difficult for the community of faith to ignore. Cone’s theological underpinning is a product of Malcolm’s reflective analysis—while other early black liberation theologians, like J. Deotis Roberts, held Malcolm’s perspective at a distance. Still, Cone’s reflection of Malcolm laid the foundation for future black theologians like Dwight Hopkins, Jacquelyn Grant, Cornel West, and Katie Cannon.

Malcolm’s intense proclamation of black pride resonated with the younger generation. His message of “self-love” was embraced by the Black Power movement led by Stokely Carmichael and Willie Ricks. This movement gained prominence after Malcolm’s death in 1965. James Cone and Cornel West were coming of age in the 1960s and are now considered the foremost authority of black liberation theology. Cone has used the dichotomy of Malcolm with American Christianity in much of his major works. Malcolm’s influence on Cone’s work strikes at the heart of the Christian church. The African American community at large embraced Malcolm as one of the leading voices from the 1960s, while the black church has been slow to acknowledge him as a leading figure during the civil rights movement.

Malcolm may have been an unwanted voice, his message may have been difficult to hear, and his critique may have caused many to shy away; however, those who took the time to listen heard the truth. Malcolm was considered a truth-teller about America, about the racist practices in America, about the black church, and about the challenges that faced black America at that time. Unfortunately, Malcolm is not viewed for his religious convictions. Many view Malcolm through his political philosophy. Viewing Malcolm by separating his religious convictions from his political philosophy, unjustly paints him as a radical. His views were radical and may have been distasteful, yet he considered himself a minister of God.[iv] While both evolved over time, his religious convictions undergirded his political philosophy.

Malcolm X may have been an unwanted voice, his message may have been difficult to hear, and his critique may have caused many to shy away; however, those who took the time to listen heard the truth.

The unwelcome voice of Malcolm was threatening because he was not afraid of the truth and understood the cost. In 1963 after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Elijah Muhammad, the leader of the black Muslim movement in America, silenced Malcolm.[v] Malcolm gave his last speech under the Nation of Islam in 1963. Shortly thereafter, he would depart from Muhammad’s organization. Malcolm’s message resonated with college-age black Americans in the 1960s—students like James H. Cone. Malcolm’s voice influenced Cone and other black theologians to view the gospel of Jesus through a different lens than white Christianity had provided. This influence continues to penetrate today as Cone’s legacy strikes fear in the hearts of those who have yet to acknowledge black liberation theology as a legitimate contribution to American Christianity.

While we may not like what we hear, listening allows for the opportunity for growth. Listening to an unwelcome voice just may spark an awareness that did not previously exist. In addition, listening to unwelcome voices demonstrates the capacity to be objective and open. It may break down walls and dismantle falsely preconceived ideas.

The Rev. Dr. Greg Johnson is pastor of Cornerstone Community Church, Endicott, N.Y.

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.

[i] Betty Shabazz, Malcolm X Speaks, (Pathfinder Publishing New York, NY, 1965, 1989), v.

[ii] James H. Cone, Martin & Malcolm: A Dream or A Nightmare, (Orbis Books, Maryknoll, NY 1991), 179.

[iii] Ibid. 167.

[iv] Ibid. 164.

[v] Betty Shabazz, Malcolm X Speaks, (Pathfinder Publishing New York, NY, 1965, 1989), 3.