To set the captives free—encountering God in the struggle for freedom

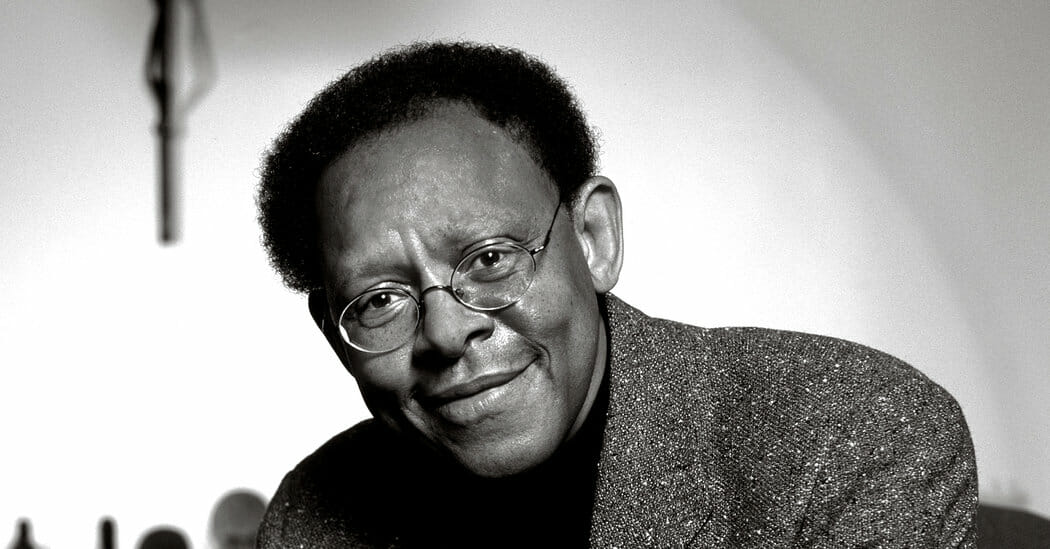

Rev. Dr. Marvin McMickle

February 24, 2020

When James Cone released “Black Theology and Black Power”[i] in 1969, he was making the claim that the center of the gospel message was God’s concern for and identification with the oppressed people of the world. This claim was based upon a reading of scripture that focused on two primary sources. First, there was the Exodus story and the deliverance of the Hebrews from 430 years of captivity in Egypt. Second, there were the words found in Isaiah 61:1 and again in Luke 4:18 when Jesus quotes from Isaiah and declares that the mission of the coming Messiah was “to set the captives free.”

If viewed through this lens, the heart of the gospel was not simply about the nature or the attributes or the names of God; topics that have occupied theologians, biblical scholars, and Sunday school lessons and sermons for nearly two thousand years. Rather, the heart of the gospel is seeing how God has entered human history to condemn those who oppress the poor and needy, and how God has acted in powerful ways to bring that oppression to an end. What difference does it make how baptism is performed or how the Lord’s Supper is served, if the churches in which those rites and ordinances were being practiced were segregated and if the people either receiving or presiding over those rituals were, at the same time participating in systems and policies that intentionally disadvantaged, disenfranchised, and dehumanized other human beings? God’s sympathies reside with and among the oppressed.

James Cone made it clear in 1969, that to be a Christian was to work with God to end that oppression. No amount of conformity to religious ritual or denominational doctrine was an acceptable alternative to engaging in the work of justice that sets the captives free! This was the primary message of the biblical prophets; religiosity is not an acceptable alternative to doing the works of righteousness and justice. Micah 6:8, Amos 5:23 and Isaiah 58:6 make that point abundantly clear. Yet, generations of white scholars and church leaders never made the connection between that clear and consistent message in the Bible and the freedom struggle going on in the United States right before their eyes. The work of God, and thus the work of those who sought to be faithful to God was to set the captives free.

Given his location as an African American theologian writing in the 1960s with the chants of “we want black power” echoing from street corners and college campuses across the United States, Cone made his claim about God even more specific. God was not just on the side of the oppressed in general terms. God was on the side of black people in this country as they struggled for freedom and dignity against racism and the presumption of white supremacy. That was the birth of what came to be known as Black Theology. It was and remains a theological formulation that must be considered within the framework of a particular context. Black Theology is not theology for the ages; it is theology for this age in which we are living with the problem of racism and white supremacy as problematic in 2020 as it was in 1969.

We need a Black Theology as a framework by which we can hear and respond to the tragic events in Charlottesville, VA in 2017 when Nazi sympathizers and white nationalists marched through the streets of that city carrying swastikas and Confederate flags. We need a Black Theology to provide a biblically grounded and historically informed position from which to respond to Donald Trump who responded to that Nazi/Klan rally by saying “there were very fine people on both sides”.[ii] It should be noted that Trump would return to those comments almost two years later, on April 26, 2019 when he said again, “His answer in 2017 was perfect, and that Robert E. Lee was a great general, and that he was the favorite general of many military leaders assigned to the White House”. [iii]

How was it possible that generations of white theologians had studied and written about the gospel, but had never made this connection between what God had done through Moses, the prophets, and Jesus, and what the church should be doing in the world in every generation in terms of the work of justice? How could scholars be at work during the “front-page news days” that was the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950 and 1960s, and they not say a word about the brutality that was being employed every day in order to maintain white supremacy in the United States? How could white preachers and teachers not make the connection between what was happening in the streets across America in terms of racial violence and race-based policies that undergirded an inequitable social order, and what should be happening in their sanctuaries, their classrooms, their neighborhoods and their own personal lives as matters of being faithful to the gospel?

Fifty years after the emergence of Black Theology, some white, conservative evangelical Christians still fail to or refuse to see the connection between the message of the gospel and the freedom struggle for black people in the United States.

Fifty years after the emergence of Black Theology, some white, conservative evangelical Christians still fail to or refuse to see the connection between the message of the gospel and the freedom struggle for black people in the United States. In 2019, Daniel Akin who is President of Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Texas said: “James Cone was a heretic & almost certainly not a Christian based on his teachings.”[iv] However, as Andre Henry points out in response, “The heresy that Cone is guilty of is denying white Christian leader’s authority to define what Christianity should look like for black people”.[v] Rather than allowing white theologians and church leaders to singularly define the frame of reference by which the Christian faith is to be understood, Cone sought to establish an entirely new frame of reference both for doing theology and for living as a Christian in American society. Henry continues:

Cone recognized that black Christians needed to embrace a frame of their own. He said, rightfully, that black people and other persecuted groups don’t organize their faith around ruminating on theological propositions, but around encountering God in their struggle for freedom.[vi]

Black Theology provides an informed position from which to ask the question of why 21st century white evangelical religion can be so outspoken on matters of abortion and “the right to life” for the unborn, but can be so silent on matters of criminal justice reform, affordable and accessible health care, quality public education, and paying a living wage to people that are trying to work their way out of poverty. Does the right to life only pertain to the womb and to the unborn child? Should it not extend to the workplace, the schoolyard, the courtroom, and the dinner table in the homes of America’s neediest families? These are just some of the policy actions that could be taken to set the captives free!

Dr. Marvin A. McMickle is professor of African American Religious Studies at Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School, Rochester, N.Y., where he served as president from 2011-2019. Adapted from the introduction to a book on James Cone’s “Black Theology and Black Power,” forthcoming from Judson Press.

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.

[i] James Cone, Black Theology and Black Power, (New York: Seabury Press, 1969.

[ii] Rosie Gray, “Trump Defends White Nationalist Protesters: ‘Some Very Fine People on Both Sides, The Atlantic.com August 15, 2017.

[iii] Jordyn Phelps, “Trump defends 2017 ‘very fine people’ comments, calls Robert E. Lee ‘a great general”, ABCNews.com, April 26, 2019.

[iv] Andre Henry, “White evangelicals’ attacks on James Cone are about power, not truth”, ReligionNewsService.com, January 9, 2020.

[v] Ibid

[vi] Ibid