Every day is Election Day

We have a deadlocked country poised to blow, with leadership throwing gas on the fire. When the election is settled, the loss, shock, cynicism, disillusionment, and abandonment so many are experiencing will remain.

We have a deadlocked country poised to blow, with leadership throwing gas on the fire. When the election is settled, the loss, shock, cynicism, disillusionment, and abandonment so many are experiencing will remain.

Veterans Day is every American’s day. It is justifiably set aside to recognize those who have honorably served in the nation’s armed forces, yet the people also have a role in national defense by virtue of citizenship.

The Serenity Prayer is not in the Bible, but arose from the lips of a renowned theologian preaching at a summer service in a small New England rural church. It is our prayer, not just for a momentary bit of spiritual relief, but for a soul-deep serenity in turbulent times, for a God-inspired courage, and for growth in our own wisdom to discern the difference between acceptance and action. In the worst of times, these crazy times, it become our earnest plea:

God, give us grace to accept with serenity the things that cannot be changed, courage to change the things that should be changed, and the wisdom to distinguish the one from the other.

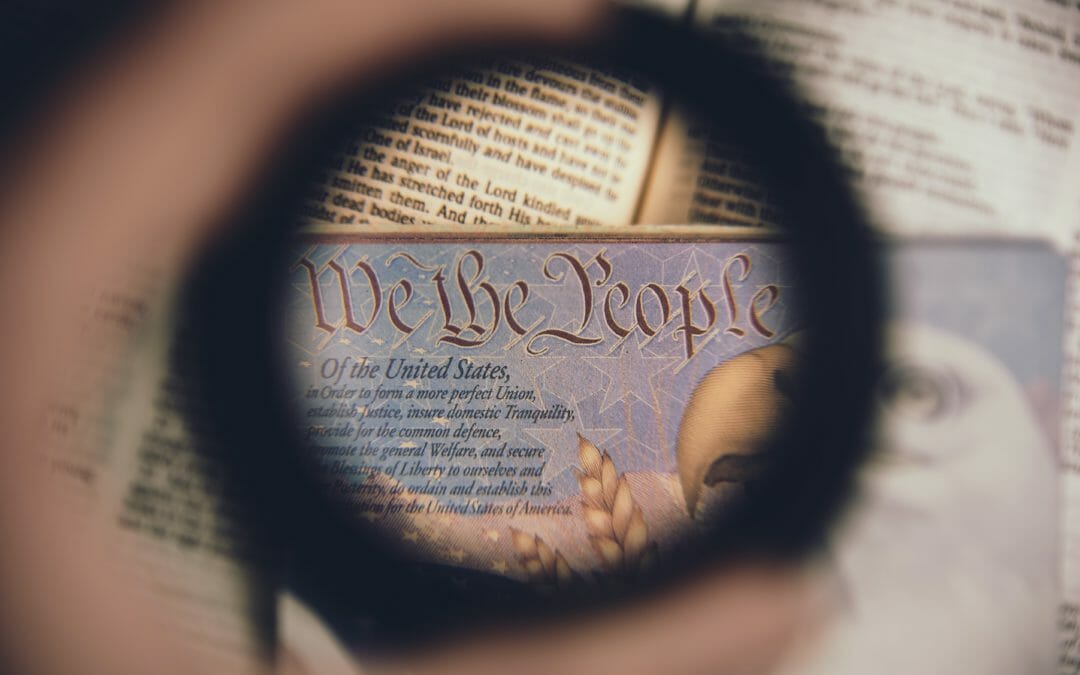

The 1787 U.S. Constitution provided a framework, penned to help us form a more perfect union. But even the framers recognized that we had not arrived at perfection. It was aspirational. The continued evolution, which has helped the document realize greater inclusivity, has helped us move closer to that ideal. I would hope that we would continue to allow our constitutional framework to expand until we reach that perfect union where all people are recognized as created equal.

As we find ourselves nearing Thanksgiving in a year filled with lamentable circumstances, we practice celebration. Celebration is not a distraction from the realities of the world we dwell in. Celebration is rooted in deep joy that can be discovered if paid attention to. Celebration was something built into the liturgical lives of the people of Israel and the early church. Celebration and joy are spiritual disciplines practiced even when times are difficult, perhaps most especially when times are difficult.

Closer to home you have greater power and influence. Get to know your neighbors and local elected officials. Work with both to brighten the corner, block, street on which you live. Invest in efforts that improve your neighborhood and community for all. Pay less attention to Washington, cable news and social media. Support local journalism.

Our soldiers who suffer from maladies due to the horrors they experienced in combat are among “the least of these.” They return home to families who love them, yet have no idea of how to help them. They return to a society that recognizes their service, honors them, and salutes their bravery, yet are unaware of the psychological, emotional, and spiritual trauma they endure.

With the country in the midst of a pandemic and election stress on the rise, congregations need to step into the gap to meet the needs not just of churchgoers, but people in their communities.

Your glory does not come from the ballot box but from God. Your honor does not come from voting but from God. That said, your glory and honor, and that of your neighbor, can be protected or jeopardize by the choices made when ballots are cast.

Nuestros Estados Unidos, se encuentran a un mes de unas elecciones que se perfilan a tener consecuencias trascendentales. Pensar que el resultado de las elecciones del 3 de noviembre puede determinarse solo por un poco más de la mitad de la población con capacidad para votar amenaza nuestro concepto de la democracia. Cuando solo un poco más de la mitad de la población elegible vota, no escuchamos la voz del pueblo, a penas escuchamos un susurro.

The year 2020 has certainly tested our anxiety, our testimony, and our resistance. Bringing out the best in us for a better year ahead in 2021 might spring not only from loving our neighbors as we would love ourselves, but also from the self-study of what it would take to honor the Sabbath as we have been commanded to do—not from Pharaoh, but from God.

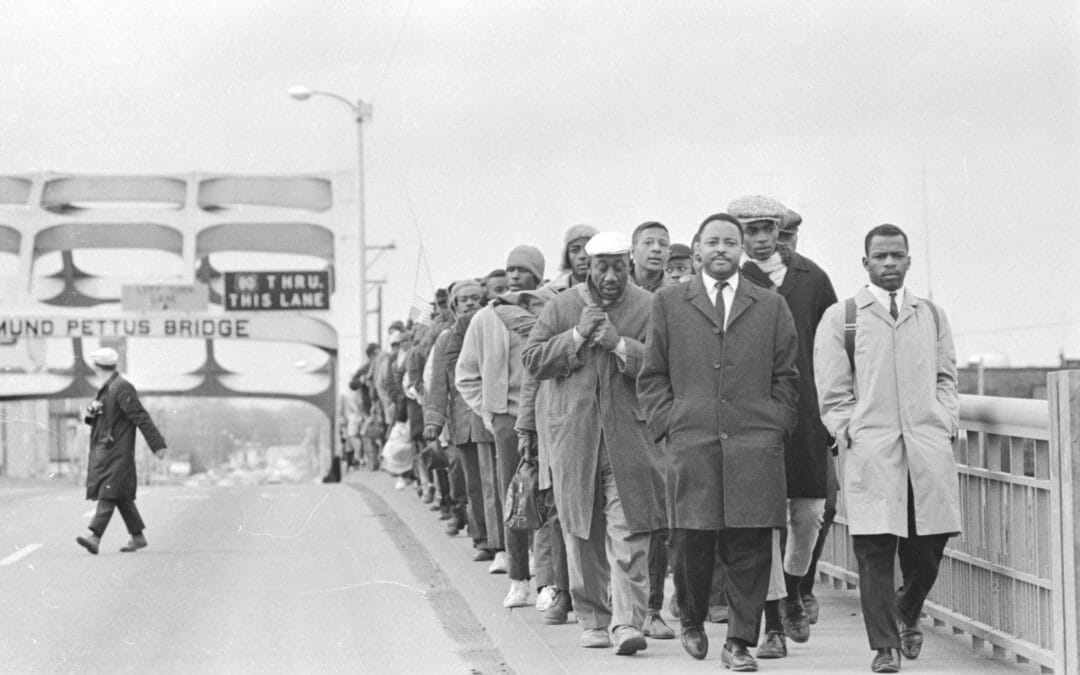

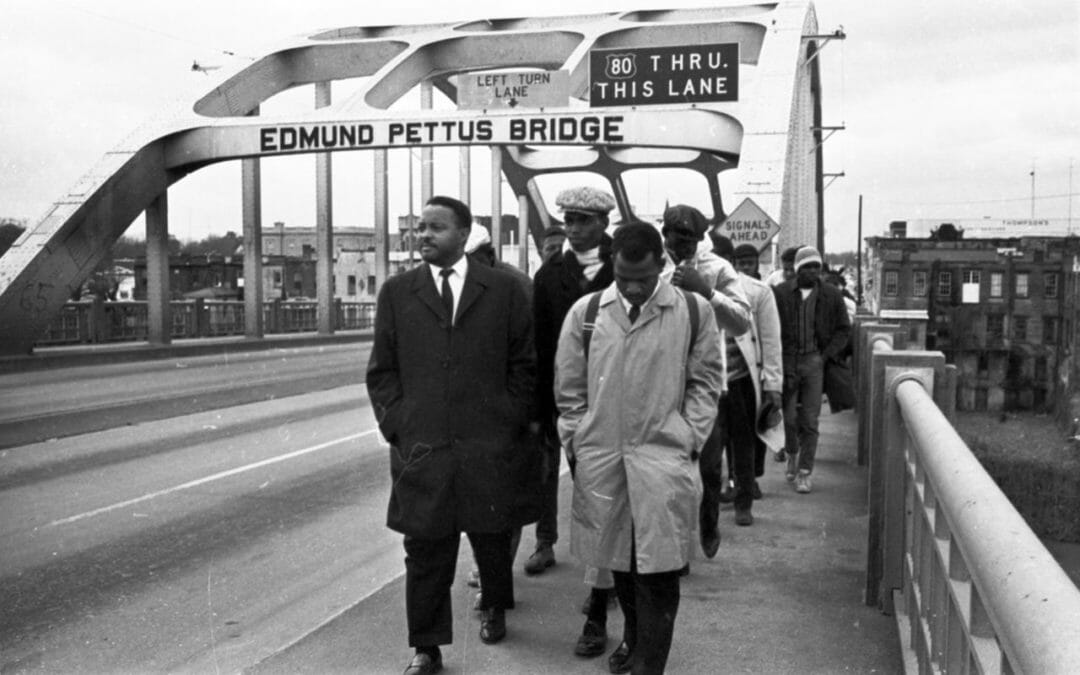

President Obama awarded Lewis the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. In remarks presenting the medal, Obama spoke of Lewis’s contributions for years to come. He stated, “And generations from now, when parents teach their children what is meant by courage, the story of John Lewis will come to mind — an American who knew that change could not wait for some other person or some other time; whose life is a lesson in the fierce urgency of now.”

Marcus’ “Meditations” is a book of reflections he wrote for himself as he sought to face the challenges of ruling the Roman empire. He lived through the time of two plagues and faced down the possibility of civil war, not to mention navigating the difficulties of court politics. Marcus sought to look at himself and his behavior and what were the best decisions he could make as a leader. He did his best to focus on his own response rather than blaming others.

The Bible’s teachings about the gospel, which has historically meant the good news of God personally working for the common good of all creation to make salvation (both spiritual and physical restoration) available to all, has been replaced by a gospel of cultural and economic power and freedom that finds its center in the United States. This nationalistic theology naturally leads to questions about who will be allowed to experience the benefits of such a salvation.

As an instrument of God’s peace, mercy, and love, I choose to join and equip others to break racial barriers, be a bridge builder in the face of injustices, and stand against the destructive systemic nature of racism.

In less than a century, we have gone from the Model T to artificial intelligence. While our lives have been altered, much has remained the same. While technology soars, resources for low-income communities continue to dwindle, and injustice against minorities remains constant.

A close friend of mine died from colon cancer at the beginning of September. COVID-19 kept us from meeting in person. It kept some family from gathering in person. It kept friends from giving each other hugs. However, it didn’t stop us from assembling together and seeing each other’s faces. It didn’t stop us from praying. It didn’t stop us from sharing memories and photos and honoring our friend’s life. It didn’t stop us from caring for the family grieving.

How can we constructively engage in politics? We must stop making the false assumption that politics and our faith aren’t intimately connected. As a part of our faithfulness and spirituality, Christians are biblically compelled to care for our neighbors, respond to the needs of the poor, and be positive contributors to society.

The presence of the Beloved is constant, infinite and everywhere. We cannot not be in the presence of God. As we grow in our capacity for prayerful listening, we can notice and join the movements of the Spirit that bring healing, liberation and life.

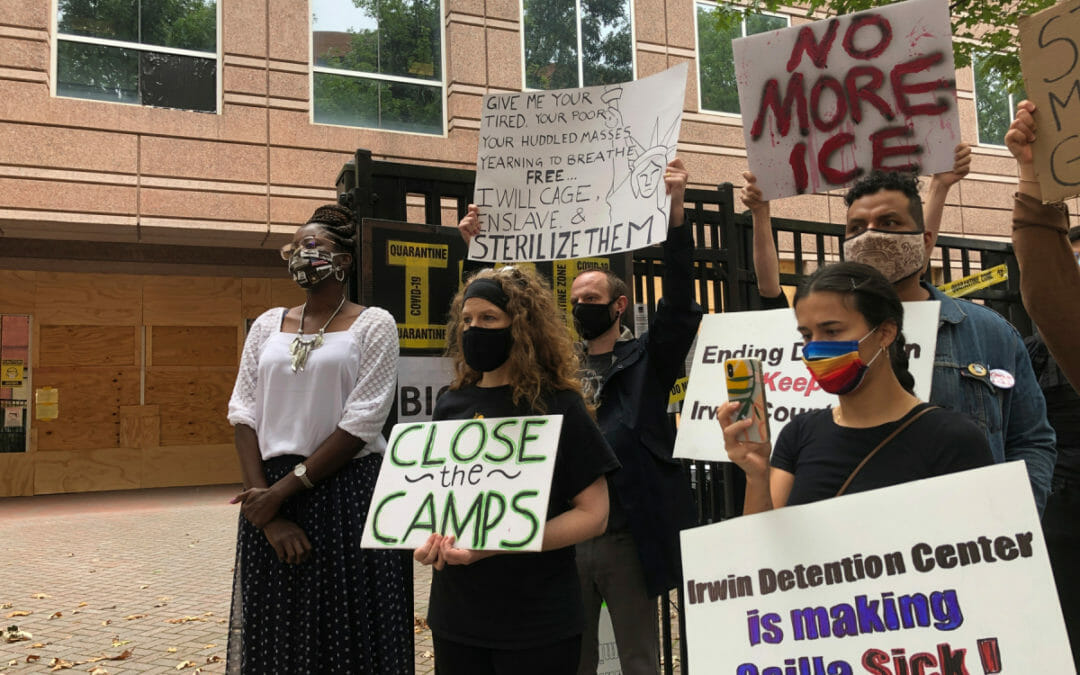

As allegations of hysterectomies performed on detained immigrant women without informed consent are under investigation, I cannot comprehend that in 2020 this practice would happen in the United States. What justification could there be to subject women to the atrocity of forced sterilization?

We must spend the next few weeks both with bowed heads in prayer and with our eyes and ears alert to what is happening in our communities. Change begins at the local level and continues upward. Until this year I was fairly cynical that my vote could really make a difference, but this year I will vote not only like my life depends on it, but like the lives of the vulnerable and the marginalized around me depend on it too.

To be a Christian citizen is to work together for the common good. If some people are not included in your conception of human flourishing, it is time to reexamine your vision.

Celebrating may seem an odd practice in times where there is much to lament and navigate. I am hopeful congregants will consider offering a word of thanks to their pastors this month. Gratitude and acknowledgment for ministry may be infrequently expressed, but certainly, for your pastor, it will be gratefully received—especially right now.

Our United States stands now one month away from an election of what feels like momentous consequence. To think that the November 3 outcome may be cast by little more than half of our voting population threatens our concept of democracy. When marginally more than half of the age-eligible population votes, we don’t hear the voice of the people, we hear barely more than a whisper.

What does third-way wisdom look like in a congregational setting, especially in 2020 when a global pandemic rages and racial tensions flare in the midst of an election year? What can church leaders do to lift disparate people above the cacophony of partisan dog whistles and political posturing?

The current pandemic has altered what we do and how we do it; the practice of communion—during the liturgy and in our daily table fellowship—is no exception. Despite our altered circumstances and the deaths of so many, the spiritual food with which we draw and serve continues to multiply. No pandemic is going to alter that.

This year on World Communion Sunday, I suggest that what unifies Christians is the yearning for communion and the connection that it represents. Strangely, there is perhaps nothing more ecumenical than that unfulfilled desire in the midst of a pandemic, one of many missed points of connection.

“The challenge is to make and keep our communities places where we can tolerate, even celebrate, our differences, while pulling together for the common good,” Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg said in 1997. “‘Of many, one’ is the main challenge, I believe, and my hope for our country and world.”

Religion and politics can be hot topics of dissension. And yet, as people of faith, it is important to us to consider the inner nature of the women and men we choose as leaders. And so, while we should not hold candidates to a litmus test of faith that is identical to ours, we are indebted to the Apostle Paul for giving us nine words to consider as we evaluate the inner light, character, and spiritual health of those who would lead.

Looking for a daily miracle helps your brain stay active by anticipating something special. For people of faith, it’s a wonderful way to live. You have to slow your pace a bit to notice, rather than rushing from task to task (or Zoom meeting to Zoom meeting).

In John 17, Jesus claims that “the hour” is at hand when he would be glorified and his disciples given their chance to be in the fullness of what his gospel proclaimed. Even when the future we see looks cloudy, the prayer Jesus offers up for his believers is one of trust, hope, and love.

We are never left orphaned. We are never forgotten.

Christ’s prayer continues to bless us, now and forevermore.

Love through the lens of emotion has a foundation of reciprocity coated in preference. From this perspective, one must have an affinity towards another before love takes root. This type of love lacks the power to deal with race or any of the world’s challenges. Love that transforms is not some sentimental outpouring feeling. The love that has the power to transform is agape, which seeks nothing in return, but is “redemptive goodwill for all men.”

The musical Hamilton asks, “Who lives, who dies, who tells your story?” But I would also ask “Whose story will we revere and embrace as patriotic? Countless people of color, women, members of the LGBTQ community and others who have cut against the grain of the majority are speaking out. Too often their words and actions are regarded as traitorous. But in this pivotal historical moment, we have an opportunity to be better.

Christian citizenship requires, not that individuals seek to impose Christianity on the society, but that individual Christians operate within the framework of Jesus’ teaching as they respond to the way government treats all its citizens, especially those who are in the greatest need.

There has always been a divide in faith and politics particularly in race, economics and power. To transform the divide, now that may be the radical and revolutionary work still needing to be done.

Be vigilant about teaching the next generation the transformative power of kindness, gratitude, and respect. Truly, the only way to save our nation and change our world is to return to “Please,” “Thank you,” and “Cover your mouth.”

As Christians, we are duty bound to go and see what our Lord thought was so important. Can anything good come from terrorist attacks or viral pandemics? Come and see. Right now, you might feel stressed under the fig tree of your own anxiety, but a belief in the restorative power of the Holy Spirit that Jesus of Nazareth embodied can carry you beyond any crisis because that was God’s plan from the beginning—to make us whole again.

Every name lost to police brutality or COVID-19 was a baby at some point. Each one held and loved. Each had dreams and expectations and hopes attached to him or her. Let us not forget their names. Let us weep.

“Ring Them Bells,” originally written by Bob Dylan for his 1989 album “Oh Mercy,” is a richly poetic song with plenty of biblical references and allusions. Many observers have pointed to the apocalyptic hints in the song, and those are certainly there. But there’s something else I hear in the song that speaks to why I like it. It reminds me of the place of the church in turbulent times.

Too often, our churches merely reflect the polarities of the day. We tend either to silo ourselves in congregations on one side or the other of the cultural divides or we fall into a kind of “don’t ask, don’t tell” silence, in which case our Christianity collapses into a privatized religion that’s polite, palatable and toothless.

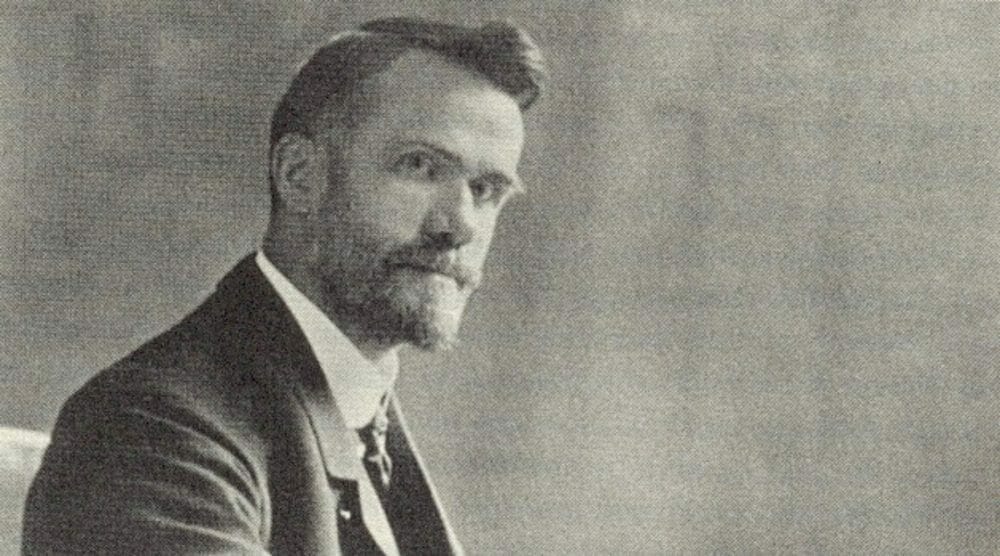

These are days we need to be daughters and sons of Walter Rauschenbusch who said goodness means following Jesus in purposeful suffering on the Via Dolorosa. These are days we need to be so good we wake up the devil and bear the marks of the Lord Jesus.

Let us proclaim that no labor is unskilled, and that all deserve a seat at the table of our economy this Labor Day. Let us advocate for the ending of exploitation of undocumented workers. Let us acknowledge that Jesus worked, and let that acknowledgment challenge and change our faith. Let us also be filled with a spirit that acknowledges that changing how our world thinks about work and workers’ place in our economy will be hard work – hard, but worth it.

We are in an unexpected place, amidst the pandemic, protests over racial injustice, economic downturn, and social isolation. Despite this, hope—which has enabled Christians and others to endure for centuries—can help us persevere.

The connection we need to be exploring is what kind of political order is fostered by our fundamental God images, symbols and rituals. How do our basic images of God legitimate or critique our institutions of governance?

Lamentations, arguably, offers an “explanation” which fits one of the dominant frames of the Bible—the Deuteronomic system of blessings and curses—and yet also offers a poetic counter to this theology.

Courage has a context. Bravery flows not from mindless risk-taking, but from compelling reasons to act on behalf of one another. We do not dare God to keep us safe no matter what foolish actions we may take.

The fact that we can regard as real something that is not or see something in an image that we want to see, suggests an openness to being misled and manipulated by the purveyors of false or misleading political claims and information. This is cause for concern in a democratic republic in which citizens are responsible for choosing their leaders.

Justice is not something we form or fashion. It is woven by God into the very fabric of creation. It has been from the very dawn of time.

Strategies must be implemented to undo the long history of racism within the North American Church culture and structure. Good intentions are not enough.

When this present moment becomes history, how will people know how your faith community responded? Will they know that many congrega¬tions quickly developed the capacity for online worship services—or even be able to watch our worship from their future position? Will they know which communities continued to supply food banks and provide housing for the home-less? Will you leave records reflecting the shift from pastoral visits to pastoral telephone calls and emails? It all comes down to how well you document these days.

Getting churches to capture this moment in time will be helpful not only for future generations. It will be also a chance for congregants to recall the immediate past and start working out what these challenging times have shown them about their own lives, as well as the inevitable travails and the graceful moments where the resilience of a local church was revealed.

Significant anniversaries provide an opportunity to take stock of where one has been and where one is headed. This month, I celebrate 25 years of ministry with American Baptist Home Mission Societies. While my portfolio has changed during that time, one constant has been my involvement with The Christian Citizen.

Members of the Karen ethnic group in Myanmar (formerly Burma) are no strangers to conditions that threaten their physical existence or inhibit their ability to think or reason freely. Thousands of Karen people were forced to flee their homes to escape violence, persecution, and war in the 20th century. The freedom they sought in Thai refugee camps left much to be desired, as they experienced degradation, restrictions on working and moving about, and food rations that often left them hungry and malnourished. The opportunity for some to immigrate to America, earlier this century, rekindled hope and dreams of better days. I interviewed 25 pastors in the Karen Baptist Churches in the United States (KBCUSA) to gain a glimpse of the challenges they are facing during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Rather than defending a traditional concept of community and common welfare in which individuals understand the connection between rights and duties, many who claim the conservative mantle substitute a doctrinaire individualism that ultimately benefits neither the individual nor society.

Through belief in Christ, the one who was born and lived among the marginalized, whose death was at the hands of the “powers that be” of this world, and whose resurrection, ascension, and promised return we take hope in, we learn to tell, and live out, a different story. The response of the faithful is not to turn a blind eye toward the sufferings of the world, nor to be willing or silently complicit partners to these sufferings taking root in political, economic, or social policies.

Hebrews 10:24-25 is a command to fellowship and to not stop gathering together as others have done. It is a command to encourage one another. How do we fulfill this biblical command while also following the local authorities’ command to “shelter in place” during these times? What is the role of the church during this historic moment? As some churches are grieving and others are calling this an opportunity for a revival, the inherent complexities of these questions and the reality of how one event can affect individuals differently are on full display.

Without negating or disregarding the significance of mothers (Mother’s Day was last month), fathers are critical to the family dynamic. The value of a father’s loving leadership is incalculable.

Father’s Day has arrived yet again, and no situation—no father—is perfect. Perhaps you have an imperfect relationship right now with an imperfect father. What’s your legacy? Visible or invisible, it’s likely there, but you might not have a full grasp of it until he’s gone. And that’s okay. Believe me, you’ll know it when it is upon you, and then it will be your legacy.

What Father’s Day should do for people of faith is open up space for us to consider the ways that earthly fatherhood does and does not map onto our experience of God. There will undoubtedly be points of slippage between our experiences of being fathered or being fathers and our experience of God’s love. For those for whom there is much distance between their personal experience and the term Father, I would invite them to find and use different terms for God.

Communal singing is an important way we as Christians connect with God and one another in worship. No matter our preferred style of singing or level of vocal skill, we use music as a source of spiritual nourishment. In times of troubles, favorite hymns or worship songs bring us consolation and comfort. In times of joy, we yearn to lift up our hearts in song. However, as we look forward to reopening our church buildings for worship, the future of communal singing is uncertain.

Part of why this protest and others are lasting so long is that we have a country full of lonely folks from Covid. Grief has been bubbling up from so much loss, and people need each other. Though Covid is still a real danger, the pandemic of racism must be defeated.

As you continue to walk through these days, reflect on what this has been like for you, and what it is like today. What do you notice about yourself? What have you learned about yourself from this time of isolation and loneliness? Or what have you learned about yourself from the enforced togetherness? What do you intend to do differently? What is God calling you to do now in this new environment?

Our nation has failed at offering liberty and justice for all, as have all nations. It is a high ideal, worthy of our every attempt. I am happy to place my hand over my heart to pledge for our Republic to continue to try its best to provide, protect, and promote liberty and justice for all, as long as all means no exceptions

The lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic should not be forgotten. Indeed, those lessons should fundamentally change how we do church, making us more creative. If we are assured of anything, it is that church can and should change so that it can meet the needs of others. After all, church was made for times like these, fostering connection when we so desperately need it.

We as a society are dealing with a lot of grief and loss right now. Woe to us, the church, if we don’t recognize and live into our crucial and unique role in this situation. In particular, I see two important but largely neglected roles for the church: public lament and grief shepherding.

There is power and a gift in grieving. When we are allowed to grieve, and when those relationships we are connected to are recognized, the process of healing is made available.

As sustained protests have multiplied, so has their powerful and passionate message: racism and police brutality are no longer acceptable. It’s a clarion call coming from a diverse, multi-racial, multigenerational Unites States of America, and it’s being echoed by our global neighbors.

Like traditional retailers whose weaknesses were exploited by the pandemic, churches suffering from the impacts of decline have similarly been placed in precarious positions. So, if we might consider this time as an opportunity for reorganization, what would such changes look like? Here are a few thoughts.

When asked what the greatest command was, Jesus said that it was to love God and love your neighbor. Right now, our neighbors need us to stay inside and to social distance. The “essential business” of the gospel is to do this. Jesus calls us to social distance, but not to be distant from each other.

We live in two Americas. One in which police brutality against people of color continues unabated and unaddressed. And another in which there are no permissible grounds for protesting white supremacy, whether taking a knee during the anthem or chanting “Black Lives Matter” in front of the White House.

Public protest by concerned citizens is one of the most basic and fundamental rights of any American citizen. Video of Floyd’s death by asphyxiation captured on multiple cell phones was one of the darkest and yet most revealing moments in recent American history.

The challenges before us are great. So is our capacity to address them. To do so, we must reject false distinctions that separate us from those with whom we share this brief moment of life. Moreover, we must learn, in Kennedy’s words, “to find our own advancement in the search for the advancement of all.”

This pandemic has pulled back the veil of our cliché-ridden faith and reminded us of what most of the rest of the world knows: life is hard, circumstances are unjust, children die, and simplistic religion is valueless.

During this season, we can use this opportunity to remove distractions that will allow for new growth in our lives and in our relationship with God.

Walter Rauschenbusch did not write only for mass audiences or only for academics, he wrote for both of them at the same time. Rauschenbusch knew movements were not sustained through sermons and articles, but through prayers (he wrote a book of social justice prayers) hymns (he collected social hymns), letters, pamphlets, and meetings (all of which he did).

Symbols can take place anywhere, even virtually, and they give rise to the same sort of reflection and deep commitment that our tradition affirms in our understanding of the ordinances.

This Memorial Day, as we remember our war dead and our loved ones, we can also remember the institutional church that had been crusted over and in decline. But looking to the lessons of history and trends of technology, we can be hopeful for the emergence of a reincarnated church that is virtual and vibrant; focused and intentional.

You might accomplish something in the latter half of this year that you previously thought impossible. When we refuse to let a good crisis go to waste, we demonstrate our ingenuity and courage. We give the people around us a sense of hope and renewal.

As we move through the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic and into discernment of what’s next, Julian of Norwich’s conviction that “all shall be well” can sustain us. This is not a dismissal of suffering, but a deep awareness of God’s presence through suffering.

As Baptists, we don’t and shouldn’t look first to the government for how to overcome most difficulties. Our commitment to the separation of church and state is rooted in our theology and our history, neither of which is changed by government efforts to provide relief in a time of crisis or shifting standards of constitutional law.

I know many are struggling and will struggle. I admit many were struggling mightily with socioeconomic injustice well before any sign of a global pandemic was on our national horizon. But I do hold out the hope and the trust that God is with us even now, providing a pathway toward the ending that benefits all creation.

And that end shall be good, whatever catastrophe bears down on us. We have a story that calls us to proclaim and provide glimpses of what J.R.R. Tolkien would call eucatastrophic joy.

Eventually the curve of COVID-19 will flatten, and in its wake will not only be those lives claimed by the virus but those who survive. Survivors will be traumatized emotionally, mentally, and spiritually. There will be a growing need for communities of faith to provide space for healing as individuals process grief.

With households becoming schools and parents and other primary caregivers managing unprecedented challenges, making family life the primary locus of Christian education can feel like just one more overwhelming task. But it doesn’t need to be.

Let us spend the rest of the COVID-19 confinement praying this threefold prayer:

First, Lord, what would you like us to stop? Second, Lord, what would you like us to start? Third, Lord, what would you like us to strengthen?

When it is safe to have dinner with friends again, go back to work, and congregate in houses of worship and schools and City Hall, we have a choice: to go back to the way things were, or to live anew.

While we collectively know that “normal” as we knew it may never return, we have signs that we will emerge from this crisis transformed. The Church is demonstrating resourcefulness and creativity in continuing to serve our communities with mission and purpose. We recognize that the good news of Jesus Christ is as important today as ever – and that the message will find a way to be heard.

In this unprecedented time, instead of asking, “When do we get to go back to leading normal worship services?” Christian leaders can seek God’s guidance in order to innovate and minister in new ways beyond the walls of church buildings and the limits of physical spaces.

During these last several weeks we have experienced many unexpected outcomes, and there will undoubtedly be more. None of us knows how to pastor during a pandemic; this is unlike other crises as we still have no idea how or when it will end. We are not going to do this perfectly. Each of us is carrying traumas of our own, and none of us is going to be at our best. Now, more than ever, we need to show ourselves – and our congregations – the grace that we proclaim.

Despite being forced to cut back on our experiences, expenses, and exposure, we collectively remain in a hurry. We were in a hurry before the virus forced us out of common spaces. We have been in a hurry seeking to adapt to sudden change. Currently, we seem to be in a hurry to get back. Back to what? Back to the office, back to school, back to profits, back to consumerism, back to sanctuaries, back to normal? Are we in such a hurry to get back that we are missing the chance to move forward into something new?

The very same systems and power structures that embody racism and oppress the most vulnerable among us under normal circumstances make the experience of living during this global pandemic decidedly unequal.

After the coronavirus has come and gone, the underlying social and economic issues will remain. African Americans will continue to face disproportionate levels of poverty, sickness, and early onsets of diseases that can cripple our bodies and shorten our lives.

Science fiction can help us imagine a future or alternative reality. While living in the uncertainty of the here and now, and learning the opportunities and limits of conducting work and worship via digital tools, here are three science fiction shows available to stream.

The struggle to care for the integrity of our creation cannot be waged and sustained apart from the struggle for justice amongst people. Biblically, justice and a spirituality of ecology are linked to each other in one ecosystem.

I was a child when the “Keep America Beautiful” public service announcement first launched in 1971, and I remember being captivated by it. Nearly 50 years later, the impact of pollution is more dire, and each of us must do our part. As the “Keep America Beautiful” announcement reminds us, “People start pollution; people can stop it.”

Earth Day reminds me that in Greek, the word for world is cosmos. For God so loved the cosmos…beyond each person on the planet, God’s love encompasses all that God created.

Since the first Earth Day in 1970, people have rallied around the concepts of conservation, environmental protection, and ecological well-being. But why do we need an annual day to remind us of these all-important ideals? Shouldn’t we have made these goals a matter of daily practice by now?

Jitsuo Morikawa was ahead of his time in discerning the intersection of social justice and ecological wholeness. His work and vision were instrumental in bringing these concerns together in the American Baptist Churches ecojustice emphasis of the early 1970s.

The Yehuda Bauer quote, “thou shall not be a bystander,” is a reminder that by doing nothing, we do not remain blameless. As we reflect this month, on those lost in the Holocaust and the redemption offered on Easter, let us remember that love sets us free and that in love there is no place for nationalism.

Churches are not often equipped as professional mental health centers, but we can do some simple things to create a hospitable culture for those in anguish.